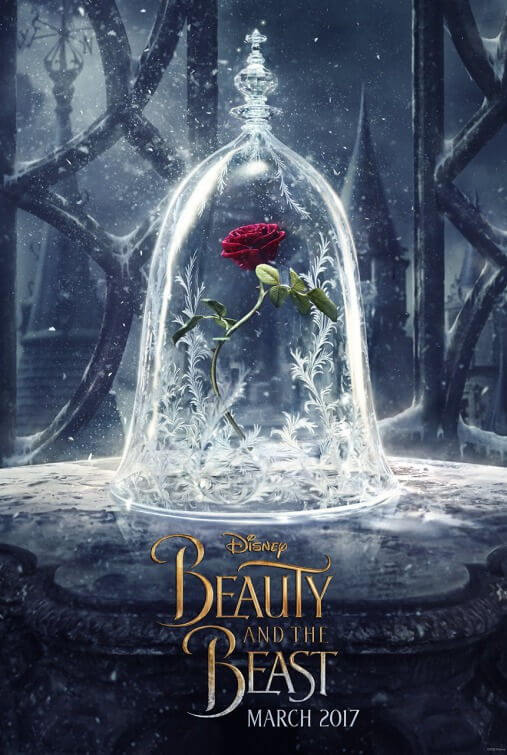

Beauty and the Beast

By Brian Eggert |

Walt Disney established his legacy by tapping into famous storybooks and adapting them into beloved animated features. Today, the studio has resorted to the cinematic equivalent of autosarcophagy, adapting its most popular animated films into (alternately) animated versions populated by (mostly) real-life actors. Though Maleficent (2014) rethought the iconography of Sleeping Beauty from the villain’s perspective, titles like Cinderella (2015) and The Jungle Book (2016) adhered to their animated counterparts all too closely. Following this trend is director Bill Condon’s version of Beauty and the Beast. Rather than going back to the original fairy tale by Mme. Leprince de Beaumont and reenvisioning it, the film reformats the studio’s cherished animated original with actors and computer-animated special FX. It’s less a remake than a replication.

Back in 1991 during the Disney renaissance of The Little Mermaid and Aladdin, Disney broke new ground with Beauty and the Beast, which employed a celebrated mixture of hand-drawn and computer animation, earning itself an Oscar nomination for Best Picture in the process. While the studio enters a new heyday with titles like Zootopia and Moana, both released in 2016, they engage in a financial sure-thing by capitalizing on their past successes with “live-action” adaptations. Instead of rethinking their former hits, they reproduce them by preserving the story with jealous devotion to the original film. The screenplay of the new Beauty and the Beast by Stephen Chbosky and Evan Spiliotopoulos contains few variations on the animated narrative, aside from a flashback or two. The film even repurposes Alan Menken’s outstanding songs, and the few additions prove forgettable.

Given how Condon’s version hits every story beat of the 1991 original, it’s pointless to discuss the plot beyond the additional scenes, which amount to unnecessary backstories for Belle and her father. Condon and set decorator Katie Spencer have gone to great lengths to recreate the look and cartoonish feel of the provincial French village that Belle (Emma Watson, demonstrating an impressive singing voice) calls home. When she eventually finds herself held prisoner by the Beast (Dan Stevens), it becomes apparent that production designer Sarah Greenwood must have had the animated original ready as a visual reference to inform every scene. Costume designer Jacqueline Durran also follows the original, from Belle’s yellow dancing gown to the tattered rags in which Beast is first seen.

However, calling the film a live-action adaptation remains a stretch. Regardless of the actors and some physical set pieces, CGI creates the film’s world. The primary difference is that Condon’s storybook has been animated in a different medium: computers, rather than brushes. Through the course of the story, any given scene has clearly been accomplished through green screen work, filling the background or animating an entire world that looks not-quite photoreal. In fact, since the original ran a brief 84 minutes and this film runs 129 minutes, it’s safe to say that more animation was used in the new film than the original. Additionally, characters like Cogsworth, Lumière, and Mrs. Potts (here voiced by Ian McKellen, Ewan McGregor, and Emma Thompson respectively) are no less animated, aside from the actors’ brief appearance in the finale.

The main differences between the two films present themselves in their animation styles. Condon’s film suggests a storybook-come-to-life quality, where the CGI animation attempts to construct photoreal renderings of fantastical landscapes and talking furniture to match the realistic presence of human actors. Except, the CGI creates an unfortunate separation between, say, Watson and her beastly counterpart. The animation used to create Beast looks cheap and unintentionally laughable. Beast walks in rigid steps, and his fur appears artificial and distractingly molded. Journey into any number of Bigfoot museums around the Redwood National and State Parks in the Pacific Northwest, and you will find a statue of Bigfoot, appearing stiff, like a bad sculpture of a taxidermized creature. Beast looks a lot like that.

The main differences between the two films present themselves in their animation styles. Condon’s film suggests a storybook-come-to-life quality, where the CGI animation attempts to construct photoreal renderings of fantastical landscapes and talking furniture to match the realistic presence of human actors. Except, the CGI creates an unfortunate separation between, say, Watson and her beastly counterpart. The animation used to create Beast looks cheap and unintentionally laughable. Beast walks in rigid steps, and his fur appears artificial and distractingly molded. Journey into any number of Bigfoot museums around the Redwood National and State Parks in the Pacific Northwest, and you will find a statue of Bigfoot, appearing stiff, like a bad sculpture of a taxidermized creature. Beast looks a lot like that.

The film’s devotion to the original comes out in its larger-than-life tone, which works when your characters are two-dimensional animations but seems inappropriate when real actors behave like cartoons. Gaston’s characterization seems just right in cartoon form, but when such a character exists in flesh-and-blood, he seems ridiculous, no matter how well Luke Evans embodies the role. Condon seems more concerned with replicating the 1991 film with a modern form of animation and (mostly) human actors that he forgets about the differences between a cartoon and live-action. Likewise, watching furniture come to life and engage in warfare with a riotous crowd plays as madcap and fun in the original film, but in the remake, it’s outlandish and over-the-top.

Condon and the writers treat the material like a stage musical, as opposed to a cinematic musical, in that every element proves overstated and shouted at the audience, including the subtext. Consider the much-discussed character LaFou, here played by Josh Gad. In the original, LaFou’s obsession with and apparent love for Gaston lingered beneath the surface. (Those who missed it, well, you’re probably missing a lot that’s happening around you.) Condon’s treatment makes LaFou a character who isn’t exactly out of the closet, but he dances with a man and exhibits some behaviors that seem like gay stereotypes. If some theaters have a problem with that, then we might wonder why they aren’t more concerned about a story in which a beautiful young woman with Stockholm syndrome falls in love with her kidnapper and, eventually, engages in a slight form of bestiality (by planting a romantic kiss on his beastly face).

Only the youngest viewers and those unversed in the original may find joy in this version of Beauty and the Beast, while those with more discerning tastes may want to seek out the wondrous 1946 version by French poet-filmmaker Jean Cocteau, or just return to Disney’s 1991 film. Condon’s version turns the original’s animated pleasures into a dull, computer-animated product from which all life has been drained. The prime example can be found in the “Be Our Guest” sequence that finds Watson seated at a table, unmoving, smiling blankly as everything around her dances in a flurry of kaleidoscopic CGI. (Watson must have spent a lot of time during the shoot surrounded by green walls, as actors in green suits danced around her.) Moments like this remind us how ineffectively Beauty and the Beast blends real-life and its animation into a convincing live-action experience; instead, it suggests a disconnect between two worlds, the actors, and their surroundings. And since the majority of these moments repeat whole songs and sequences from the original, the entire experience feels like it exists not for creative reasons, but purely commercial ones.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review