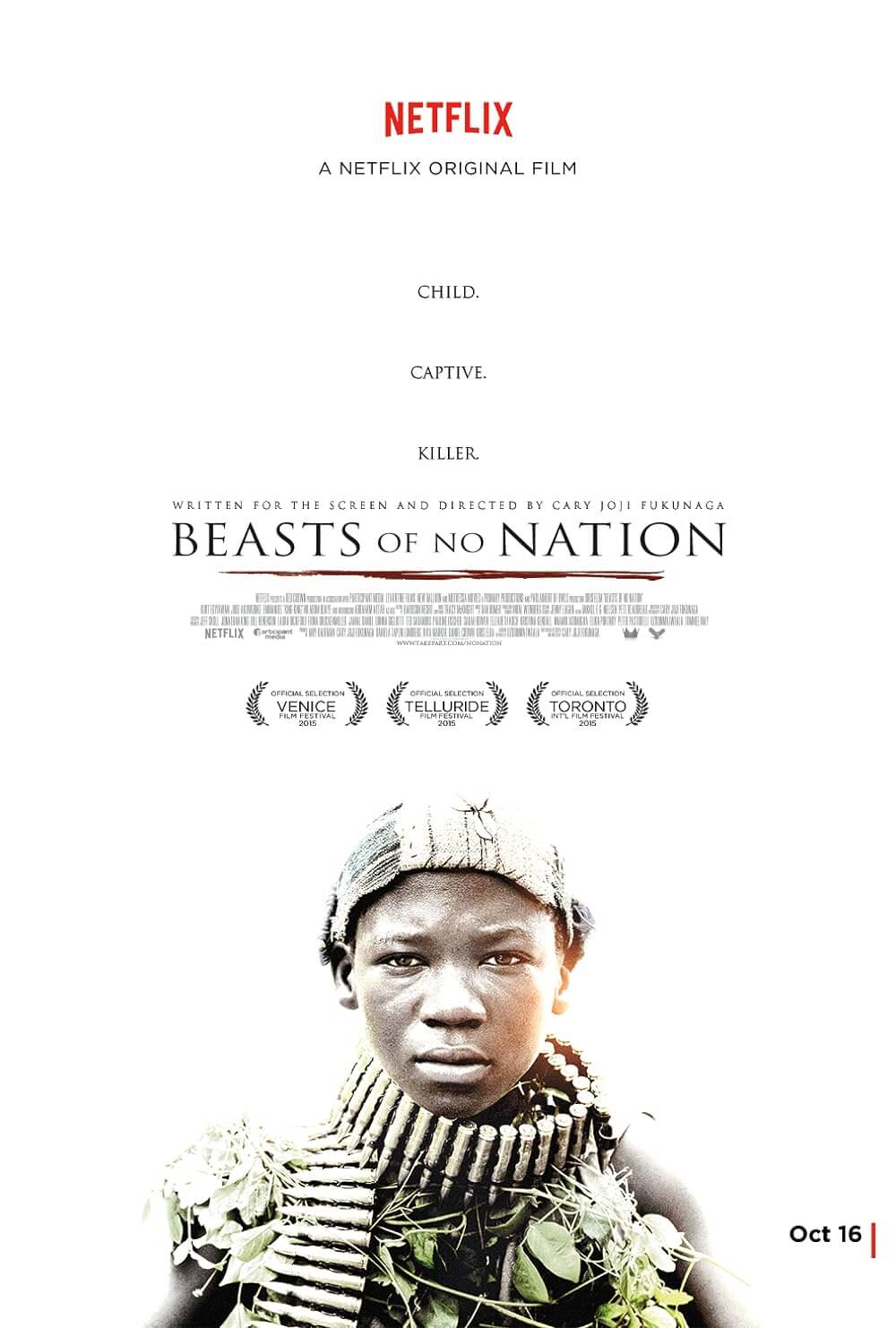

Beasts of No Nation

By Brian Eggert |

In Beasts of No Nation, a little boy named Agu goes from playing games with his friends to becoming a brainwashed, drug-addicted, sexually abused guerilla soldier. Played by young Ghanaian actor Abraham Attah, the character tells us he’s “a good boy from a good family” in an unnamed African country. He spends his days thinking up creative ways to pass the time, like gutting a tube television and using the empty frame as an “imagination TV”. One of his friends changes the channel, announces “kung fu”, and other boys act out a lightheartedly choreographed fight scene, watched through the TV’s vacant insides by armed soldiers in his village. Before long, the audience watches on their own televisions (insides intact) as Agu transforms into a killer, assimilated and trained by a charismatic warlord known as the Commandant, played in a powerhouse performance by Idris Elba.

We watch at home because Beasts of No Nation is Netflix’s first original feature film, having debuted on their streaming service the same day as its limited release into Landmark Theaters. This method of distribution is bound to change the way films are made and released. To be sure, it affords Netflix free reign in terms of content, as they need not worry about a harsh MPAA rating or audiences unwilling to flock to theaters to see a grim story of deep, painful humanism. And though Netflix has fewer distribution restrictions and exposes a wider sampling of movie-watchers to an arthouse release, the potential damage their method will have on the theater industry proves worrisome. Nevertheless, audiences will not have to wait months until the film arrives on disc media or rental streaming services to see the punishing, heartrending experience of director Cary Joji Fukunaga’s take on the 2005 novel of the same name.

Although implications suggest Beasts of No Nation takes place in Nigeria (author Uzodinma Iweala is Nigerian-American), the sad truth is that we cannot be certain where the film takes place, as several African countries have endured similar events to those that occur in the film: When his village is swept away in a sudden outbreak of violence as “rebels” search for government sympathizers, Agu watches his mother and baby sister escape with other refugees, while he regrettably stays back with his father and older brother, both of whom are summarily executed as “spies”. Dashing into the woods, Agu finds a cadre of lost boys overseen by the Commandant, guerilla fighter and master manipulator. Part of an anti-government movement overseen by a Supreme Commander somewhere off-screen, the Commandant proceeds with the expectation that his young soldiers will tear across the countryside and earn him a promotion to General.

Agu, thrust into moral disorder and donning crude fatigues, gradually learns to kill when the Commandant puts a machete into his hand and tells him to put it in the skull of a weeping captive. Scenes such as this are difficult to endure but handled with incredible verisimilitude by Fukunaga, the film’s director, screenwriter, cinematographer, and producer. Muted colors, precise handheld observations with Fukunaga’s camera, and shooting on-location in Ghana render a powerful degree of poetic realism. In some ways, the approach could be described as documentarian; massive outdoor assaults and skirmishes capture footage that looks like on-the-scene video journalism. Elsewhere, when Agu has his first taste of drugs, the magenta color-timing transports us to the protagonist’s head for a vivid sequence. Fukunaga’s control over the production remains impressive throughout, and after Jane Eyre (2011) and his work on HBO’s first season of True Detective, the director stands as a confident visual stylist.

But the director’s style recedes behind the performances at the film’s center. Foremost is Elba, whose turn in Mandela: The Long Walk to Freedom (2013) rendered an unnatural, impression-of-a-performance, whereas here he disappears into his role. Just when the Commandant seems summed up, Elba shows us another layer, from freedom fighter to pied piper, from rebel to tyrant, and finally arriving in a doomed and deserving solitude. It might be Elba’s best performance outside of Luther. Meanwhile, Attah delivers one of those child portrayals that feels so raw and expansive that we must wonder how someone his age could channel such emotions. Suffice it to say, much is demanded of the young actor, and he never fails to make us believe that Agu has suffered through his experiences. Alongside Attah is the equally excellent Emmanuel “King Kong” Nii Adom Quaye, who plays Agu’s fellow soldier and friend Strika, a sensitive boy who refuses to speak.

Though certain scenes, such as those between the Commandant and his superior, don’t fully translate the book’s child perspective, Fukunaga nonetheless attempts to see through Agu’s eyes, without politics or prejudice, throughout the majority of the film. Agu’s narration and a scene of trippy colors hint at the perspective, but the formal presentation can sometimes feel, if only momentarily, uneven. For example, Dan Romer’s score of moody electronic tones doesn’t fit with Agu’s perspective, whereas a wonderful tracking shot as Agu finds himself at his most confused and violent seems at once formally brilliant and thematically inspired. These momentary lapses do not detract from the overall presentation, however, especially because the actors and harrowing situations have drawn us in so completely. Overall, Netflix and Fukunaga have delivered a stunning debut, forcing us to wonder if they can maintain the level of Oscar-caliber quality for future original programming. Had the film been a full theatrical release, there would be no cause for exception or anything but high praise.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review