Barbie

By Brian Eggert |

When Greta Gerwig signed to direct Barbie, she faced a myriad of challenges. How do you make a movie that does justice to the venerable brand, carefully overseen by Mattel? How do you make the doll, first introduced in 1959, feel relevant given today’s multifaceted discussions of gender and feminism? Can you make a movie about Barbie without it being about more than shimmering pink surfaces? How do you speak to the doll’s promotion of unrealistic and consumerist beauty standards, the perpetuation of gender stereotypes, and its damage to self-esteem? Moreover, how does making a movie about a Barbie not inadvertently carry on those negative effects? And how do you address these issues in a $100 million production without becoming a sociopolitical soapbox, and should you even address these issues? Assuming you do, who’s the audience for this movie? Will it be geared toward the same target market as the dolls, young girls between 3-12 years of age? Or a more specialized audience? Beyond all of that, Gerwig had to make a movie that somehow tackles these questions about the rather precarious icon but also connects with the summer movie crowd.

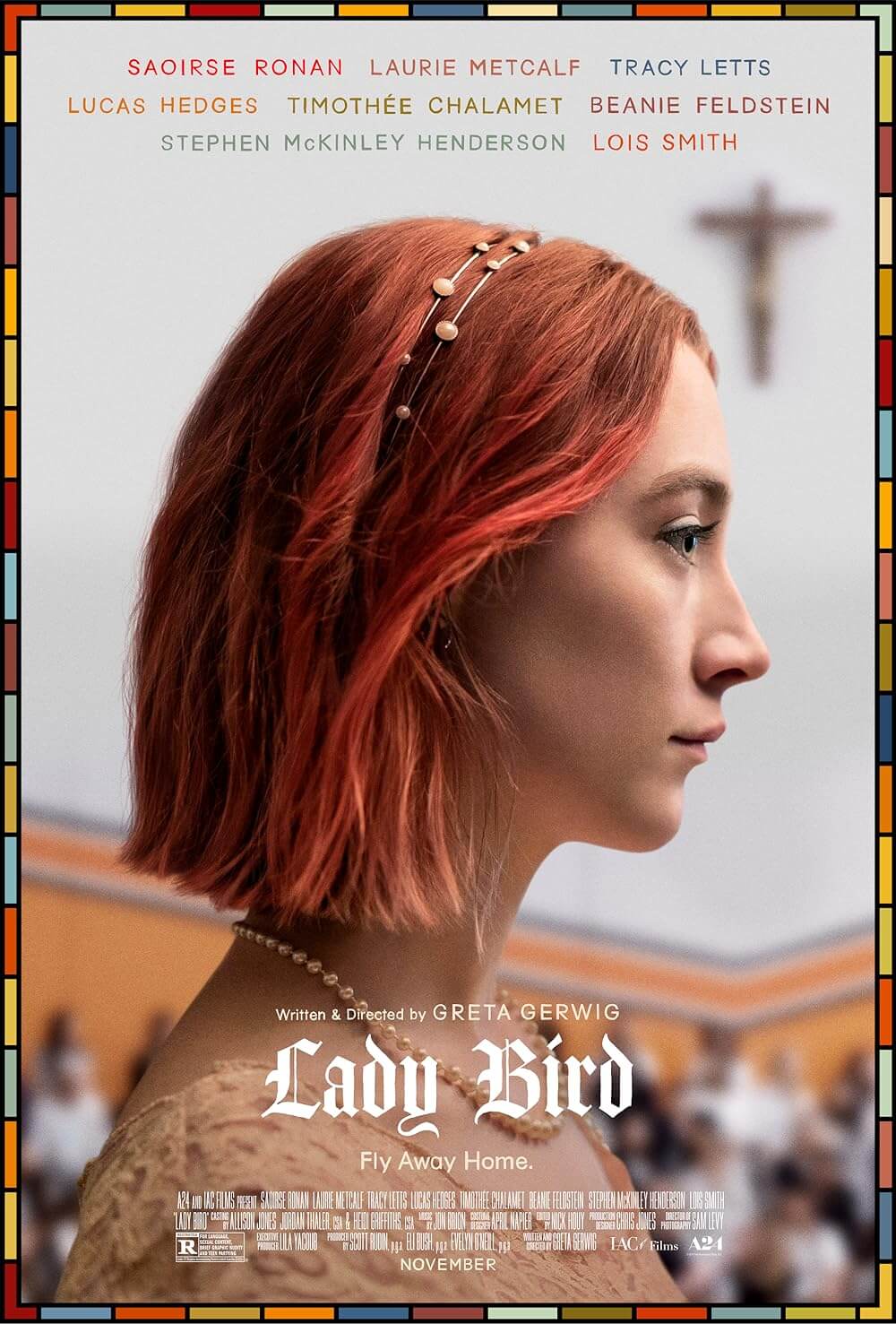

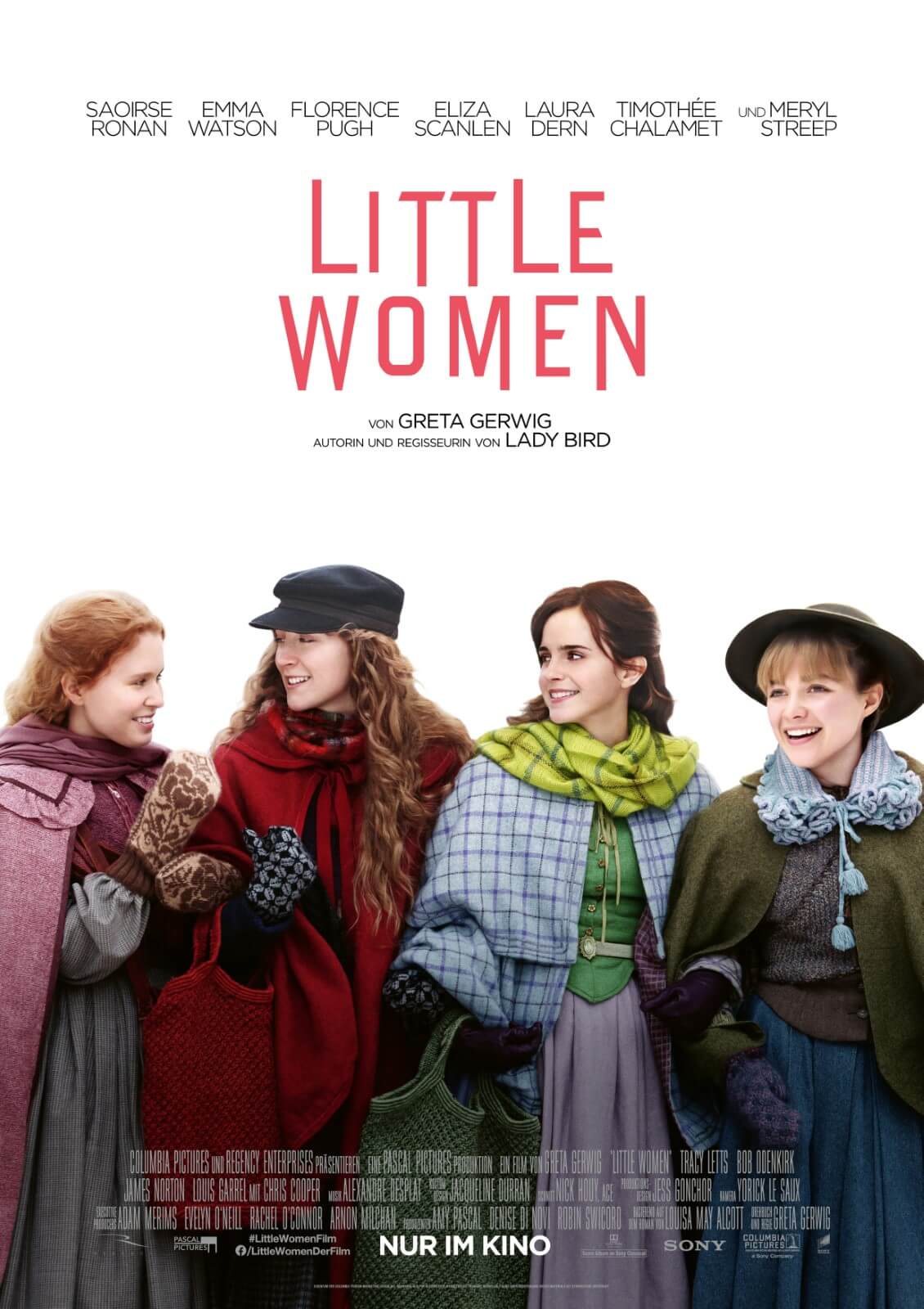

Not surprisingly, Gerwig delivers a sublimely optimistic, glittering production—until reality truncates what become complex characters. The result is a clever satire, with a riotous sense of humor and existentialism that springs from its relatable emotions—all contained in a formally ambitious candy-colored product. Barbie ends up about as good as it could be, largely thanks to Gerwig’s self-awareness as a filmmaker and storyteller. She may not adequately address every question listed above, and the plot meanders at times, but the director of Lady Bird (2017) and Little Women (2019) leaps into a big-budget studio project with a defiant energy and unmistakably personal stamp. Given that the Barbie movie could have been a plastic and hollow commercial with no human identity, designed to unabashedly reinforce the toy brand, it’s refreshing to see a filmmaker apply her critical perspective. Gerwig treats the titular character not as an aspirational ideal but as someone whose journey represents the many challenges and contradictions of being a woman.

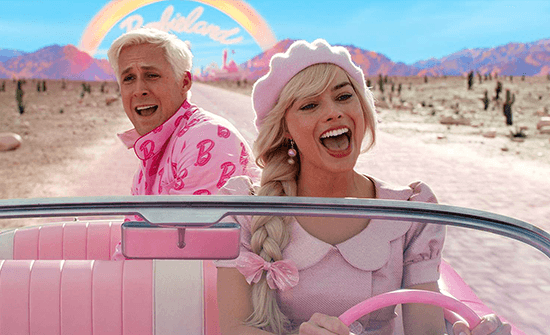

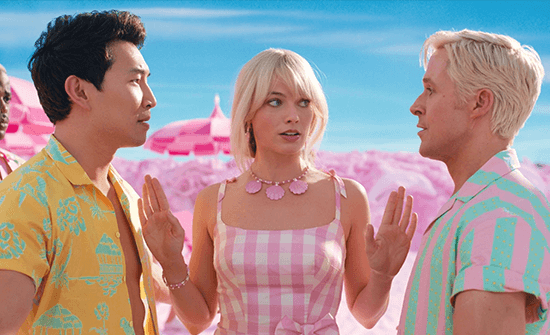

The screenplay by Gerwig and collaborator-partner Noah Baumbach borrows a page from The LEGO Movie (2014), telling the story that links the toy, who inhabits a land of make-believe beholden to the almighty toymakers, and the player with said toy in the real world. Helen Mirren narrates, introducing Barbie Land, where the so-called stereotypical Barbie (Margot Robbie) believes, “All problems of feminism and equal rights have been resolved.” Barbie lives in a blissfully idealized matriarchal world, with an all-female President and Supreme Court. Some initial gags find Barbie waking up in her dreamhouse, on a picture-perfect day, where she pantomimes showering and eating before greeting the other women in Barbie Land—all named Barbie, save for the pregnant Midge (Emerald Fennell). The male dolls, all named Ken, save for the odd Allan (Michael Cera), vie for the Barbies’ attention—none more so than the fragile-egoed alpha Ken (Ryan Gosling). Gerwig gives us a typical day-in-the-life view of Barbie, complete with a drive to the beach in her pink Corvette, only to have her interrupt an impromptu dance number by impulsively asking, “Do you guys ever think about death?”

With imperfect behaviors adding up, stereotypical Barbie consults with “weird” Barbie (Kate McKinnon)—the victim of haircuts and marker makeovers by her player—about her dark feelings, fear of cellulite, and flat feet. She learns that she must meet her player in the real world to “restore the membrane that separates our world from theirs” (or whatever). The movie never addresses whether, for every Barbie doll, there’s an alternate Barbie Land with its own human owner; the fantasy-world-to-child ratio is never explored beyond this single example. In any case, Barbie sets out, with alpha Ken tagging along, to find the child who’s playing with her and learn what’s causing her to have anxiety and thoughts about death. But upon arriving on Venice Beach, Barbie finds she’s no longer in the feminist utopia where women can be anything. Instead, she’s the object of male onlookers and not actually valued by young women, whereas Ken feels empowered by our world’s patriarchy—to the degree that he wants to apply what he’s learned to Barbie Land and reshape their world.

With imperfect behaviors adding up, stereotypical Barbie consults with “weird” Barbie (Kate McKinnon)—the victim of haircuts and marker makeovers by her player—about her dark feelings, fear of cellulite, and flat feet. She learns that she must meet her player in the real world to “restore the membrane that separates our world from theirs” (or whatever). The movie never addresses whether, for every Barbie doll, there’s an alternate Barbie Land with its own human owner; the fantasy-world-to-child ratio is never explored beyond this single example. In any case, Barbie sets out, with alpha Ken tagging along, to find the child who’s playing with her and learn what’s causing her to have anxiety and thoughts about death. But upon arriving on Venice Beach, Barbie finds she’s no longer in the feminist utopia where women can be anything. Instead, she’s the object of male onlookers and not actually valued by young women, whereas Ken feels empowered by our world’s patriarchy—to the degree that he wants to apply what he’s learned to Barbie Land and reshape their world.

Gerwig explores the imaginative limits of Barbie with her production, offering inspired asides like the opening’s ode to 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), where a clan of young girls toss aside their baby dolls for an adult woman toy, which is bound to destroy their self-image for years to come. Gerwig has clearly let her creative impulses run wild to inspired effect, conjuring dance sequences inspired by The Red Shoes (1948) and Singin’ in the Rain (1952), with marvelous, bubblegum-colored imagery shot brightly by cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto. Another sequence through a gray-walled Mattel office feels ripped from the drab cubicle underworld of Brazil (1985), therein the opposite of Barbie Land’s pink paradise. Production designer Sarah Greenwood brings all the artistry Hollywood can muster, delivering an “A” level treatment to what looks like a more expensive version of that “Barbie Girl” music video by Aqua. Costume designer Jacqueline Durran draws from actual Barbie-brand merchandise, giving well-versed fans a knowing wink of Barbie garb throughout history and underscoring the oddities for everyone else (2009’s Sugar Daddy Ken, anyone?).

Most impressive is how Gerwig and Baumbach’s script gives these characters dimension. Robbie’s version of the doll has profound conversations that challenge simplistic notions of womanhood, questioning her role as a doll with the help of some real-life humans, Mattel employee Gloria (America Ferrera), and her adolescent daughter Sasha (Ariana Greenblatt). Although Barbie thought she was a role model, Sasha calls her a “professional bimbo,” forcing her to reassess everything. Gloria gives more than one speech about what it means to be a woman, and it’s an inspirational rallying cry for the others—almost an extension of Saoirse Ronan’s Little Women monologue: “Women, they have minds, and they have souls, as well as just hearts. And they’ve got ambition, and they’ve got talent, as well as just beauty.” But even the supporting characters feel like they have more depth than their surfaces imply. Issa Rae, Simu Liu, Dua Lipa, Hari Nef, Kingsley Ben-Adir, Alexandra Shipp, Sharon Rooney, and the rest of the ensemble appear on the same wavelength as Gerwig, perfectly aligning with the unique band of humor and message about gender equality.

Barbie’s formula might even risk playing into Ken’s hands, since Gosling’s needy man character threatens to steal every scene with his charming stupidity. Barbie returns to her homeworld to discover that her fellow Barbies are spellbound by the Kens, their dreamhouses turned into absurdist man-caves called “Mojo Dojo Casa Houses.” To whatever degree the dopey, perpetually ignored Ken almost sneaks away with Barbie’s movie, the various Kens remain the butt of Gerwig’s best jokes. To be sure, Barbie is riotously funny and quotable, with Barbies brainwashed by the Kens to be “really invested in the Zack Snyder cut of Justice League.” With the help of Gloria and Sasha, Robbie’s Barbie deprograms the other Barbies and retakes control of Barbie Land by manipulating the Kens into a war that descends into a boy-band dance-off. Most of the humor isn’t so sly, but it’s bluntly subversive and always referential to the toys (“I’d like to see what kind of nude blob he’s packin’ under those jeans,” one of the Barbies remarks), earning the film its PG-13 rating—a surprising twist on a property often associated with younger audiences.

Barbie’s formula might even risk playing into Ken’s hands, since Gosling’s needy man character threatens to steal every scene with his charming stupidity. Barbie returns to her homeworld to discover that her fellow Barbies are spellbound by the Kens, their dreamhouses turned into absurdist man-caves called “Mojo Dojo Casa Houses.” To whatever degree the dopey, perpetually ignored Ken almost sneaks away with Barbie’s movie, the various Kens remain the butt of Gerwig’s best jokes. To be sure, Barbie is riotously funny and quotable, with Barbies brainwashed by the Kens to be “really invested in the Zack Snyder cut of Justice League.” With the help of Gloria and Sasha, Robbie’s Barbie deprograms the other Barbies and retakes control of Barbie Land by manipulating the Kens into a war that descends into a boy-band dance-off. Most of the humor isn’t so sly, but it’s bluntly subversive and always referential to the toys (“I’d like to see what kind of nude blob he’s packin’ under those jeans,” one of the Barbies remarks), earning the film its PG-13 rating—a surprising twist on a property often associated with younger audiences.

Not everything about Barbie works. When our hero faces the all-male executive team behind Mattel, she meets the company’s CEO, played by Will Ferrell, who behaves like, well, Will Ferrell—albeit unleashed as a destabilizing force in the movie. Along with the other executives, the CEO chases after Barbie to put her “back in her box,” propelling much of the second act. Yet, this conflict is never satisfyingly resolved; the CEO just sort of goes away at the end, presumably returning to his office to look over fourth-quarter projections. However, the chase leads to an overwrought scene where Barbie meets her inventor, Ruth Handler (Rhea Perlman), in a white void—rather like Neo confronting the architect of The Matrix, with equally mind-bending implications. Moreover, the film never reconciles how, in the real world, Barbie continues to represent an unrealistic ideal for young girls. Sure, Gerwig makes inclusionary strides by showcasing Barbies of various races, hair colors, and body sizes, offering several Barbies who don’t look like the blonde-haired, blue-eyed “stereotypical” Barbie. Even though Gerwig addresses how not everyone looks like this or feels like they belong in Barbie’s idealized world (thanks to some well-timed criticisms by the narrator), the overall critique feels toothless in reality. So while Gloria comically suggests there should be an “Irrepressible Thoughts of Death Barbie” or “Cellulite Barbie,” don’t expect Mattel to release those dolls anytime soon.

A Mattel commercial insists that “When a girl plays with Barbie, she imagines everything she can become.” But at least one scholarly study from 2014 suggests, no matter how ingrained the you-can-be-anything message, most young girls don’t learn that from Barbie; instead, they learn about a gendered world where women are valued for their sexualized appearance. That said, it would be absurd, and wishful thinking, to imagine that Gerwig could ever make a takedown movie about Barbie with the full cooperation of the corporation—even if Mattel seems to be a good sport, given how the company and its leadership are represented onscreen. Rather, what Gerwig offers is a clear-headed assessment of the doll, with equal measures of nostalgia and playful critique; an acknowledgment that, in reality, gender discrimination is very real; and a concession that Barbies represent a fantasy world. Barbie is also just a lot of fun, amounting to one of the year’s best comedies. It may not resolve the conflicts between Barbie the capitalist entity, the sexualized object, and the powerful feminist icon, but it doesn’t have to. Gerwig uses Barbie as a way of accessing real-world themes of womanhood in a delightfully entertaining way.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review