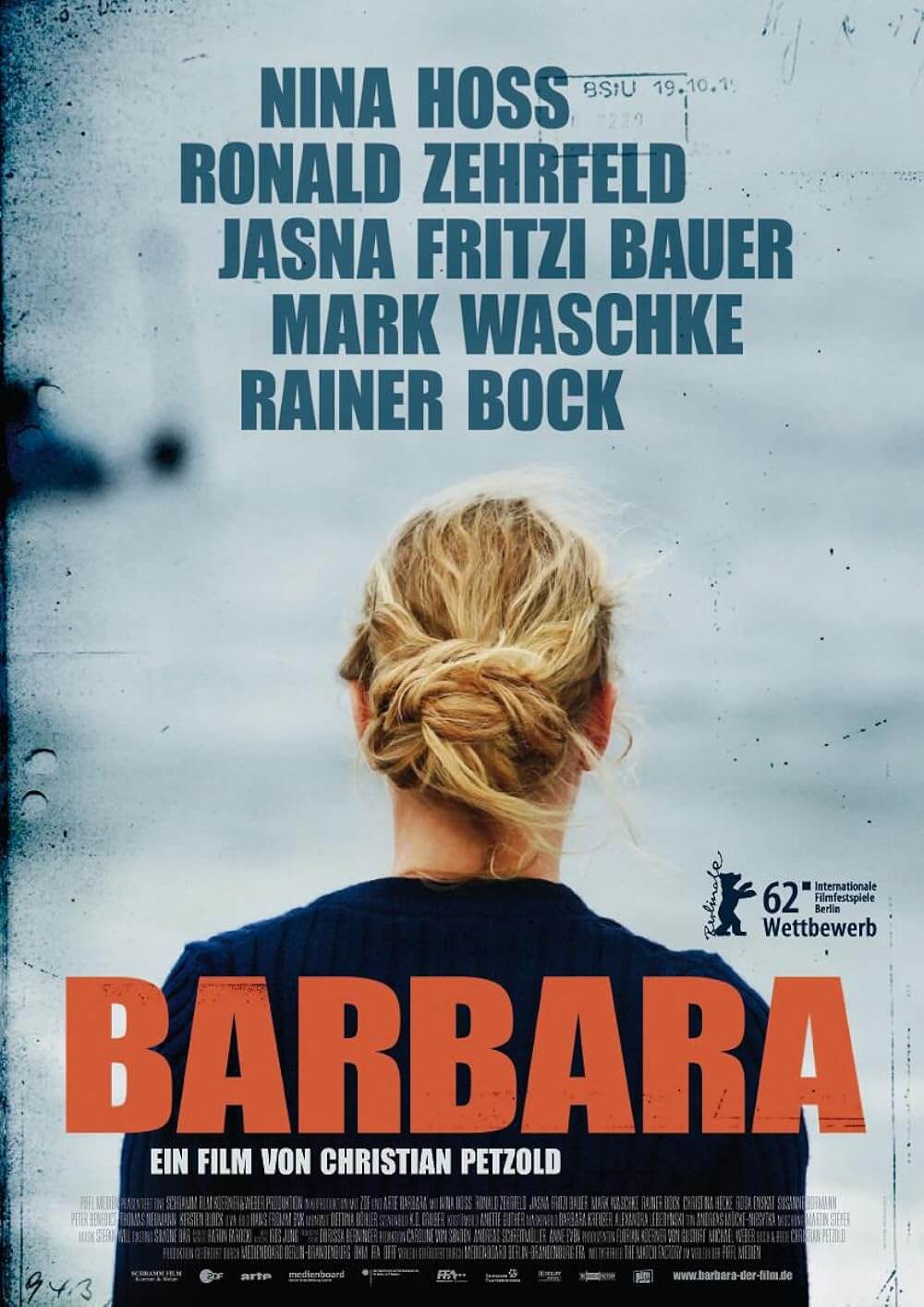

Barbara

By Brian Eggert |

A quiet thriller of internalization, Barbara takes place in East Germany in 1980, a decade before the fall of the Berlin Wall. The finest of the collaborations between director Christian Petzold and his recurrent star, Nina Hoss, the film considers life under the constant eye of a tyrannical government. The German Democratic Republic spread an air of oppression that, along with a dearth of commodities, kept the so-called workers’ state in paralysis. The socialist ideals on which the country was founded warped into a ubiquitous paranoia that your neighbor or coworker might become an informant, and the fear not that the Stasi would arrest you, but they would use their information about you to destroy your personal and professional lives. Those who were smart maintained two versions of themselves: the version shown to the world, and a truer version that remained hidden. Mining his childhood visits to relatives in the GDR, Petzold considers, with characteristic intertextuality, complex characters within entrenched sociopolitical conditions. Although the GDR’s control over its people proves dispiriting, Petzold also brings a critical eye to West Germans quick to exploit their neighbors, leaving anyone caught between these two worlds trapped. Barbara finds Petzold at his best, questioning borders and exploring human melodrama under the shadow of politically charged contexts.

The star of Petzold’s Jerichow (2008) and Phoenix (2014), Hoss plays a physician named Barbara who finds herself relegated to a bleak apartment in a provincial town to practice medicine at a small hospital—her punishment for applying for a visa to join her boyfriend in West Germany. In her new surroundings, she upholds a wall and remains bitterly suspicious of her colleagues. The impenetrable Barbara has good reason not to show emotion and be cautious around André, the earthy doctor played by Ronald Zehrfeld (a dead ringer for Russell Crowe)—Stasi agent Schütz (Rainer Bock) has asked him to spy on her. But André, too, has been assigned his country post as a result of his mistakes, endearing him to Barbara’s situation and assuring he will be a poor informant for Schütz. Barbara finds some small measure of hope with the arrival of Stella (Jasna Fritzi Bauer), a young patient from Torgau, the toughest reformatory in the GDR. Stella is pregnant and desperately wants to escape the country. Barbara also has plans to sneak away with her lover. Given their shared desire, Barbara and Stella form a curious, unspoken bond that reminds the former of what it means to feel passion rather than constant suspicion.

Although Petzold grew up in West Germany, his parents originated from the GDR, and his family spent vacations in the East. In an interview with Film Quarterly, the director talked about the economic disparities between the East and West, and how, despite his father’s unemployment, their family was still better off than those in the East. “When we traveled to the GDR in our West German car we were still like kings.” During a scene in which Barbara meets her boyfriend Jörg (Mark Waschke) in the woods, Petzold pulls back to a brief scene when Jörg’s driver, in a Mercedes, meets a man driving a Trabant, the boxy, utilitarian car produced in the Eastern Bloc. The man from the East cannot help but stop on the side of the road to admire the Mercedes; he remarks on the steering wheel cover that keeps the driver’s hands warm in the winter. It’s as though his country has been visited by an alien from another world. The scene is about how the GDR deprived its residents just as it is about the West’s smug superiority and willingness to exploit the East.

Although Petzold grew up in West Germany, his parents originated from the GDR, and his family spent vacations in the East. In an interview with Film Quarterly, the director talked about the economic disparities between the East and West, and how, despite his father’s unemployment, their family was still better off than those in the East. “When we traveled to the GDR in our West German car we were still like kings.” During a scene in which Barbara meets her boyfriend Jörg (Mark Waschke) in the woods, Petzold pulls back to a brief scene when Jörg’s driver, in a Mercedes, meets a man driving a Trabant, the boxy, utilitarian car produced in the Eastern Bloc. The man from the East cannot help but stop on the side of the road to admire the Mercedes; he remarks on the steering wheel cover that keeps the driver’s hands warm in the winter. It’s as though his country has been visited by an alien from another world. The scene is about how the GDR deprived its residents just as it is about the West’s smug superiority and willingness to exploit the East.

Note the presence of certain cultural objects throughout Barbara, which are present as cruel reminders of the diversions that Western society can afford, yet they are generally restricted by the GDR. Barbara reads Stella a copy of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn at night, the book being a symbol of Stella’s desire for a youthful escape. In André’s office, he keeps a print of Rembrandt’s painting The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, and the outwardly GDR-compliant doctor reveals himself to Barbara as an astute and observant reader of art. Later, as André shows more interest in Barbara, even offering to cook her an impromptu ratatouille in an achingly romantic scene, he suggests that she read The District Doctor by Ivan Turgenev—a story about longing and searching for meaning in one’s life. If these particular references seem apt, overly so, it is in service of Petzold’s approach, which employs a subtly expressive use of melodrama to underscore his themes. It is the same reason Petzold uses water in the film as a symbol that restores, saves, or cleanses—it’s an unmistakable element the viewer can use to interpret the otherwise restrained emotions of the characters.

Petzold’s criticisms of both sides of Germany are best articulated by Barbara’s romantic affiliation with Jörg, whom she apparently met during one of his trips to the GDR. Jörg arranges to meet Barbara for brief sexual encounters in the woods or a rendezvous in a hotel room, but she begins to question the nature of their relationship. Watch the bedroom scene when Jörg sits Barbara on his lap like a child and intimates that, when she finally escapes to West Germany, she will no longer have to work. Another woman in a similar affair with a man from the West confesses to Barbara the materialistic nature of her relationship, and by extension, Petzold underscores how men trafficking goods from the West see Eastern women as exploitable. Barbara is not interested in such things, however. In contrast to Jörg, André sees Barbara as a professional. Both have been removed from better hospitals in Berlin and reassigned to the current position in the countryside. He gives her the use of his makeshift lab, and when a patient requires surgery, he knows her experience enough to insist that she administer the anesthesia. Moreover, André respects Barbara as a woman deserving of courtesy. When he walks in on her getting dressed, he averts his eyes and gracefully backs out of the room, into the hallway of the hospital, the sexual tension cooking far beneath the surface.

Barbara is about the distinction between being watched and being seen. At several points in the film, André could have made a romantic advance toward Barbara, but instead, he chooses to see her, rather than merely observe or gaslight her—which seems to be what both Jörg and Schütz have in mind. The Stasi officials who ransack Barbara’s apartment and conduct cavity searches watch for further signs of dissent. They’re not interested in Barbara as a human being; they’re interested in control. Jörg has similar ambitions, treating Barbara as nothing but another materialist acquisition, and he’s willing to spend a small fortune to arrange for her escape by the North Sea. But her time living in the GDR has left Barbara wary of being watched and controlled. She resolves to stay behind with André, who sees her and gives her agency enough to make the oppressive and poor culture of the East tolerable. Their small section of the world finds two people connecting in a meaningful way. Elsewhere, she might be forced to navigate through political or economic systems that prove less important to her than making a connection and feeling like she has control over her life.

However, the conclusion of Barbara finds the character neither rescued by a man nor delivered from the gloom of the GDR. Her choice to remain in the East results from her decision to send Stella to the West in her place—a beautiful nighttime sequence, which appears to be shot day for night and realized with fluid shadows that lend the images a fantastic quality. Barbara has given the young woman hope for a better life, whereas she remains behind. Though she does not escape the dynamic between East and West Germany, and she’s no closer to avoiding the prying eyes of the GDR, she resolves to endure within familiar conditions alongside someone who understands her. Quiet defiance and companionship is the best she can hope for, Petzold seems to argue. Barbara’s yearning for independence on her terms, a quality emphasized by her choice to use a bike as transportation, is constant throughout the film. The ending may not be happy, not in the traditional sense anyway, but it shows a character chipping away at the impenetrable walls she has erected around her. If history has shown us anything, that is the first step towards healing.

Rich with political, artistic, and narrative contexts that reward multiple viewings, Barbara depicts a familiar world in which a woman must always be looking over her shoulder for who’s watching her. Petzold won the Silver Bear for Barbara at the Berlin Film Festival. His austere and controlled direction is superb for the layers he brings to this character study, in that he allows the viewer to experience how the GDR scrutinizes Barbara, as well as how she functions within her headspace as the observed. Hoss, as ever, brilliantly restrains herself throughout the film within a stoic visage that, only in moments of extreme rarity, show any sign of the person inside. Petzold reflects this with a severe soundscape, including almost no music and the heightened sounds of the sea and wind. Quite similarly to Phoenix, Hoss plays a character the viewer yearns to understand throughout the picture, and only in the final, raw moments does she reveal herself. The experience is one of absolute restraint, followed by a rare, nuanced display of emotion that feels like an outpouring, and further, speaks to Petzold’s control of the material.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review