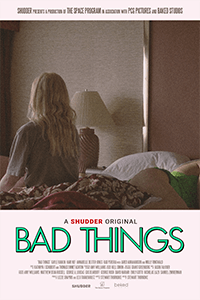

Bad Things

By Brian Eggert |

Imagine The Shining (1980), except not set in The Overlook Hotel. Instead, it’s set in the plain, oppressively beige Comley Suites, resembling the generic surroundings of what might be a Best Western or Holiday Inn. Instead of a nuclear family terrorized by an alcoholic father who’s puppeteered by evil spirits to murder them, supernatural forces plague a mentally unstable member of a queer friend group, bringing her mommy issues to the fore. If you can see that in your mind’s eye, you have some idea of what to expect from Bad Things, writer-director Stewart Thorndike’s feminist answer to Stanley Kubrick’s classic. The movie arrives complete with a wintry setting, creepy twins (here, two models who went out jogging and died of exposure as opposed to axe-murdered children), and entrenched lore about five deaths at the hotel in three decades. But it’s far from the masterful, symbol-laden, maze-of-a-movie that inspired it. Thorndike’s promising cast and often campy tenor will doubtless earn Bad Things a few admirers, but at 85 minutes, it barely gets going before the end credits start to roll.

Gayle Rankin from Netflix’s GLOW headlines the cast as Ruthie, a young woman who arrives at her late grandmother’s hotel to prepare the establishment for a future sale. She’s joined by her girlfriend Cal (Hari Nef), who hopes Ruthie will propose soon, even though their relationship has hit a rocky patch following Ruthie’s recent affair with Fran (Annabelle Dexter-Jones). For some reason, Ruthie allowed their friend Maddie (Rad Pereira) to bring Fran along if only so Maddie has someone to sleep with. Fran has issues too, including cancer treatments that may or may not be entirely fabricated for attention. And it’s unclear what Ruthie and the others need to accomplish on the trip. Thorndike’s script never outlines a series of tasks or objectives they need to complete to prep the hotel, making the narrative’s impetus feel rather hollow. But if their interpersonal drama is any indication, they have enough to worry about without the hotel and its ghouls.

Sure enough, the friends begin to see creepy signs of specters, including one drawn straight from Ruthie’s childhood trauma—when her mother left her alone at the cold hotel for three days without food, and she almost lost three fingers to frostbite. Indeed, another presence is Ruthie’s disturbed mother, who remains offscreen but continuously texts her daughter: “I love you so much.” Ruthie remains cagey about her mother with the others, often losing her temper and shutting down any conversation about the topic. Her erratic behavior includes obsessing over a video of a business guru (Molly Ringwald) giving a TED Talk about hospitality, continuing her flirtation with Fran, and reacting strongly to Brian (Jared Abrahamson)—a maintenance guy lingering around the property, supposedly to fix a pool. These dynamics might be more engaging if the hotel was more evocative as a location, but it has little more character than a franchise located near an airport.

Thorndike’s sophomore effort follows her 2014 debut, Lyle, where Gabby Hoffmann and Ingrid Jungermann played a lesbian couple, the former of whom begins to suspect that their neighbors belong to a Satanic cult à la Rosemary’s Baby (1968). Thus far in her career, Thorndike seems to be re-envisioning classic horror films with women LGBTQ+ characters, which is a noble enough enterprise. However, seeing the filmmaker tackle an original concept would be more compelling. This is especially true because homage invites comparison. Alas, Bad Things is muddled by a poor sense of spatial geography, whereas The Shining outlined the hotel’s layout only to disorient the viewer later on. For instance, Ruthie uses a chainsaw to cut up a fallen tree on the road to the hotel in the first scene, suggesting the hotel is secluded. But the ending, with touches of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), hints that a strip mall is right around the corner. Such details are less the result of a fascinating puzzle that the viewer hopes to solve than a confusing execution by Thorndike and her editors.

Thorndike’s sophomore effort follows her 2014 debut, Lyle, where Gabby Hoffmann and Ingrid Jungermann played a lesbian couple, the former of whom begins to suspect that their neighbors belong to a Satanic cult à la Rosemary’s Baby (1968). Thus far in her career, Thorndike seems to be re-envisioning classic horror films with women LGBTQ+ characters, which is a noble enough enterprise. However, seeing the filmmaker tackle an original concept would be more compelling. This is especially true because homage invites comparison. Alas, Bad Things is muddled by a poor sense of spatial geography, whereas The Shining outlined the hotel’s layout only to disorient the viewer later on. For instance, Ruthie uses a chainsaw to cut up a fallen tree on the road to the hotel in the first scene, suggesting the hotel is secluded. But the ending, with touches of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), hints that a strip mall is right around the corner. Such details are less the result of a fascinating puzzle that the viewer hopes to solve than a confusing execution by Thorndike and her editors.

The movie’s disparate story elements rarely come together in a way that satisfies, and the characters behave in ways that lack emotional or motivational clarity. The actors do their best with the material, but they have no hope of invigorating the underwritten scenario or roles. Consider Fran. One minute, Fran declares to Ruthie, “I am here to save you,” telling her, “We should leave.” The next, Fran is dropped at a nearby train station with an infected leg and needs a hospital visit, completely abandoned without warning by her so-called friends. Moreover, Fran seems particularly plagued by the hotel’s ghosts. Perhaps this is because Fran’s presence nags at Ruthie, who’s at once drawn to Fran yet seems inconvenienced by her cancer and the fissure she has caused between Ruthie and Cal. Where does this leave Cal and Maddie? On the sidelines, mostly. To be sure, Ruthie is this film’s Jack Torrence, whose emotional state amplifies the hotel’s ghosts for the other inhabitants.

After premiering at the Tribeca Film Festival this year, Bad Things was acquired for release on Shudder, where horror aficionados may crack its code or have fun trying. In the press notes, Thorndike says the film is about motherhood: “A celebration of this first primal relationship and how blurry and complex that can be.” Given the film’s absent mother, it’s worth questioning the degree to which anything in Bad Things really happens. I suspect much of the movie takes place in Ruthie’s head, making certain ambiguities rather conveniently written off as the projections of a disturbed main character. But unlike Kubrick’s film, Thorndike doesn’t leave clear footsteps in the snow for us to follow; her film wanders freely, which is surely the point, though it doesn’t invest us in a step-by-step tension that keeps us rapt. Instead, the homage makes a pointed feminist contrast designed to emphasize aesthetic and representational differences, prompting what might become a fascinating conversation about the two texts. But on its own, the experience feels underdeveloped and unsatisfying.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review