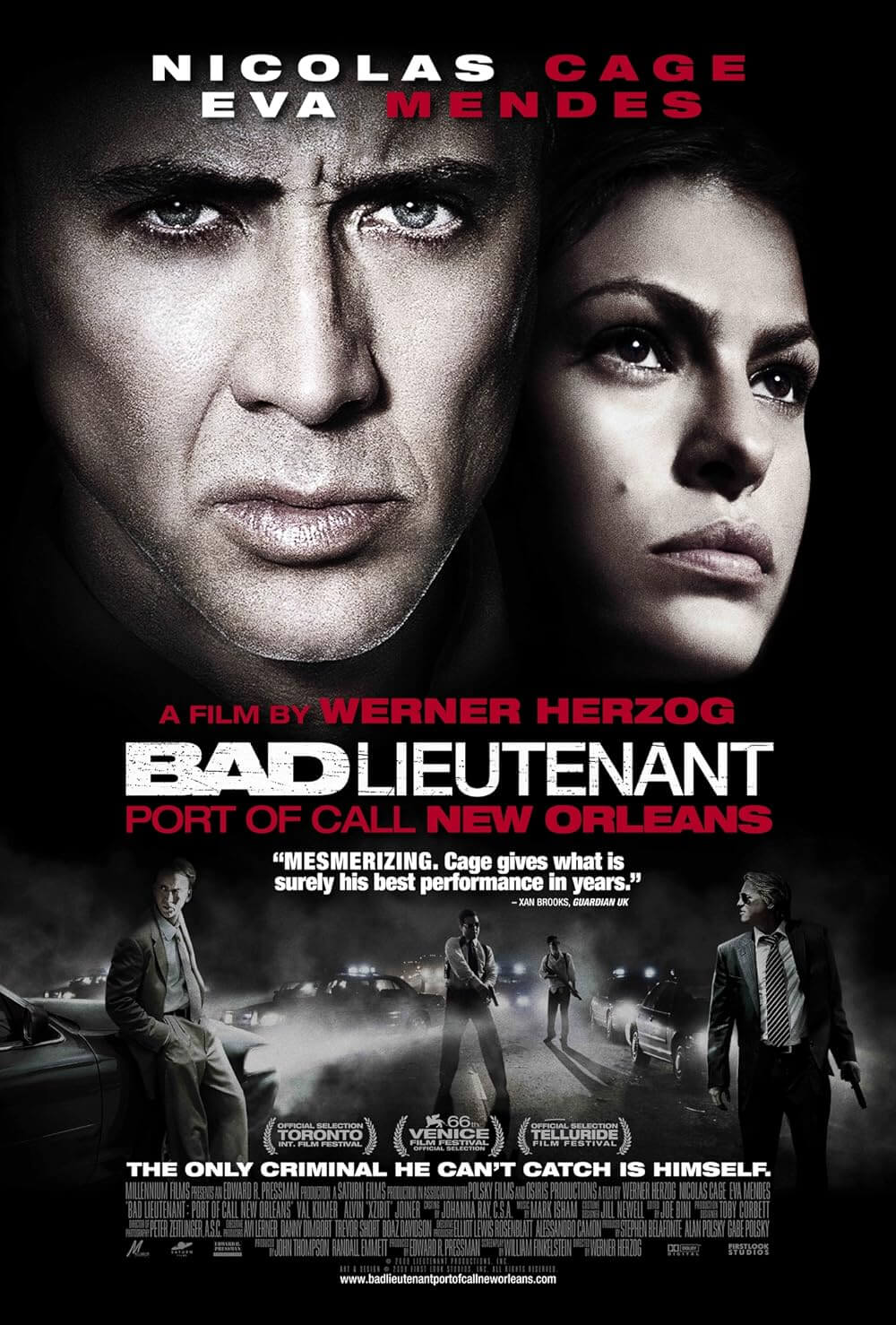

Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans

By Brian Eggert |

What to make of Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans? This thematic remake of Abel Ferrara’s 1992 picture Bad Lieutenant, which starred Harvey Keitel in one of his best performances, comes from the obsession-obsessed director Werner Herzog, and it boasts one of the best performances from its star, Nicolas Cage. Connected to the Ferrara film only by its title and the portrayal of a drug-addicted policeman, Herzog takes an entirely different approach to the subject matter. Instead of punishing the audience with a relentless sense of Christian guilt on a cinematic road to Hell, Herzog explores the enduring and very real lunacy of corruption and addiction.

Cage’s New Orleans cop Terence McDonagh earns himself a promotion and a permanently disjointed back in the first scene, when during Hurricane Katrina he risks himself to save a jailed prisoner from drowning in putrid floodwaters. Months later, McDonagh is a Lieutenant Detective. His right shoulder hangs asymmetrically lower than his left, and his body and mind are permanently contorted by his ever-present pain. McDonagh’s addiction to Vicodin wears down his tolerance, leading to hefty use of cocaine and other narcotics. Imagine TV’s Dr. House with a gun and an unlimited backstage pass to the corrupt streets of post-Katrina New Orleans, multiply that by a thousand, and you’ll have at least a vague concept of where McDonagh’s character derives his motivation.

That Herzog shows his audience the origins of McDonagh’s increasingly warped behavior makes Cage’s character more sympathetic than Keitel’s origination, but no less a monster. Ferrara’s film began with Keitel already well into his drug habit. Herzog shows us, if only for a moment, that McDonagh is a duty-bound cop who, even while trying to balance his cocaine highs and heroin lows, still tries to reinforce the law. Of course, he ignores the law himself, exploiting the power of his position at every turn. But in him exists a foundational morality that shows its shame-ridden head amid his horrible crimes.

In a scene mirroring one in the 1992 film, the bad lieutenant pulls over a young couple for a shakedown. He robs them of their illegal drugs, threatens the frightened young man with jail time, and then forces the man’s girlfriend to pleasure him at gunpoint. In another scene, he violently hassles two elderly women for information, slapping them about and cutting off one’s oxygen tube. Be it hallucinating iguanas or enjoying a hit from his personal crack pipe, Cage’s character searches for extreme moments with that larger-than-life edge the actor is now famous for. Sometimes his over-the-top acting does his film a disservice, but in Herzog’s hands, the actor’s hysterics feel brilliantly unhinged. It’s a performance like this that makes an audience remember the greats—Adaptation, Leaving Las Vegas, and Raising Arizona—and forget all the junk in which Cage usually appears. This performance reminds us that, when not involved in a hackneyed thriller or overblown actioner, Nicolas Cage can be a damn fine performer.

In a scene mirroring one in the 1992 film, the bad lieutenant pulls over a young couple for a shakedown. He robs them of their illegal drugs, threatens the frightened young man with jail time, and then forces the man’s girlfriend to pleasure him at gunpoint. In another scene, he violently hassles two elderly women for information, slapping them about and cutting off one’s oxygen tube. Be it hallucinating iguanas or enjoying a hit from his personal crack pipe, Cage’s character searches for extreme moments with that larger-than-life edge the actor is now famous for. Sometimes his over-the-top acting does his film a disservice, but in Herzog’s hands, the actor’s hysterics feel brilliantly unhinged. It’s a performance like this that makes an audience remember the greats—Adaptation, Leaving Las Vegas, and Raising Arizona—and forget all the junk in which Cage usually appears. This performance reminds us that, when not involved in a hackneyed thriller or overblown actioner, Nicolas Cage can be a damn fine performer.

Here and there, the film concerns itself with a central case where McDonagh tracks down drug-dealing murderers, but nevermind the details of the plot. The case is a framework on which Herzog and Cage drape their character. We meet his sex-worker girlfriend, Frankie (Eva Mendes), who decides to reform herself after meeting McDonagh’s rehab-bound father (Tom Bower) and his beer-sucking girlfriend (an unrecognizable Jennifer Coolidge). When Frankie tells him that she’s going to an AA meeting, McDonagh stares at her blankly and says, without a hint of irony, “Does that mean you don’t want any of this blow?”

Herzog’s film is certainly more enjoyable than Ferrara’s, in the sense that Herzog and Cage appear to be having one helluva time putting all this insanity onscreen, whereas Ferrara’s film was an effectively depressing downward spiral of drugs and self-destruction, ending with the death of Keitel’s character and leaving the audience in a funk. Herzog, working from William Finkelstein’s pulpy screenplay, sets up a playground where Cage’s Mad Hatter character can frolic. And instead of sending him on a fatalistic journey into self-destruction, Herzog suggests, hilariously, that McDonagh gets away with it all. There are about five minutes in the finale dedicated to everything wildly working out for McDonagh, despite all the holes he’s dug for himself. Isn’t it more realistic, though, that the corrupt and horrible cop gets away with his crimes, that there isn’t a poetic and movie-friendly justice in the end?

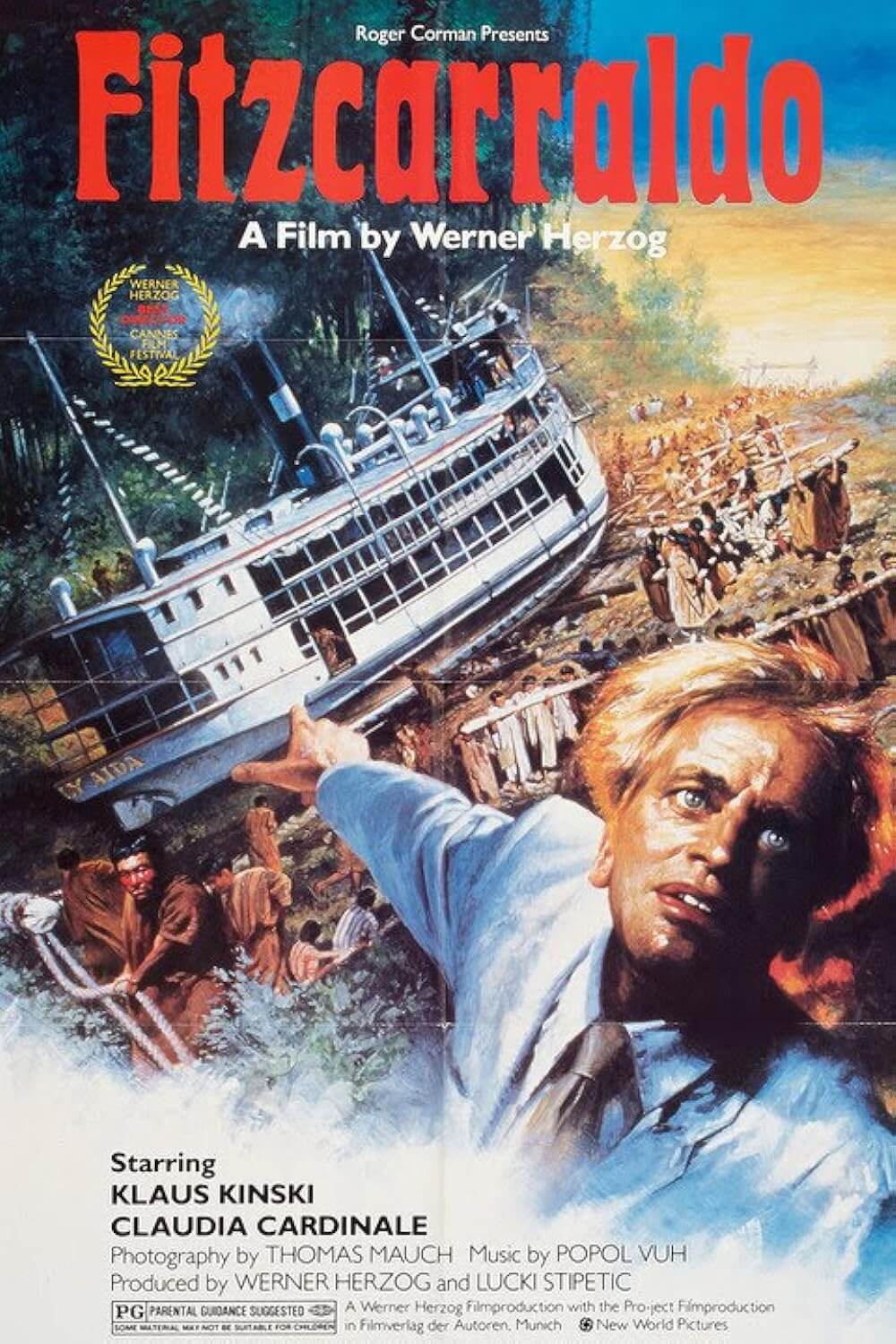

Though Herzog has not made a perfect film, Port of Call New Orleans is more provocative than most pictures out there right now, even if it doesn’t compare to the director’s masterworks like Fitzcarraldo and Aguirre, the Wrath of God. It challenges the viewer to figure out what to make of the protagonist, because more than just an engine propelled toward his own destruction, Cage’s McDonagh catches himself and stops before he goes too far. Rather than plummeting off the deep end, he finds a balance between a respectable life and one filled with debauchery. Herzog has always been more interested in the continuation of a mad existence versus its messy conclusion, and that fixation is alive and well throughout this crazy, uneven, kind of brilliant motion picture.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review