Bad Lieutenant

By Brian Eggert |

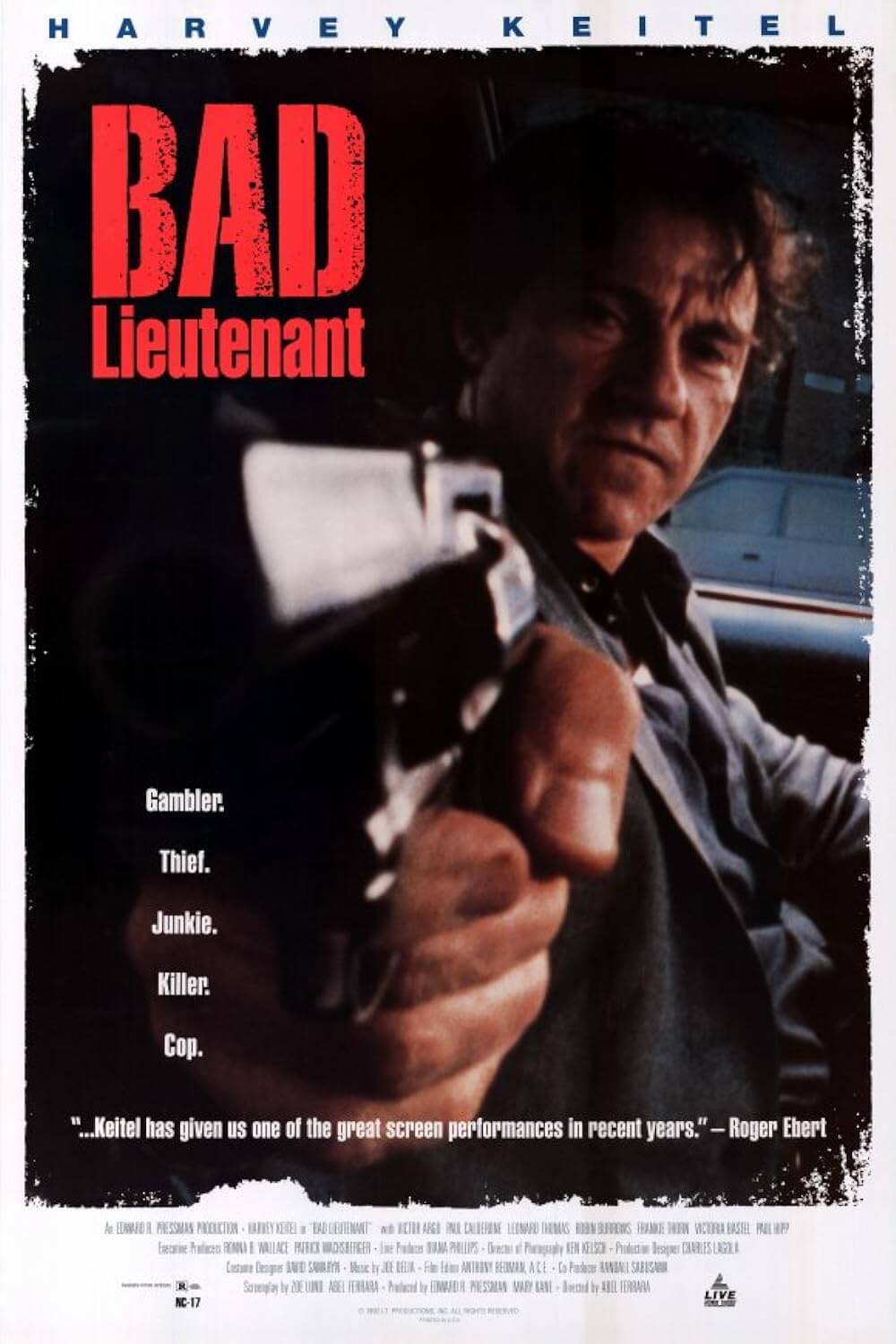

Abel Ferrara’s Bad Lieutenant broke into the American independent film scene in 1992, boasting an incredible performance by its star, Harvey Keitel, and the commercial curiosity expounded by an NC-17 rating. Ferrara’s exploitation cinema brought him some acclaim with Fear City and Ms. 45, but nothing in his career justified the filmmaker artistically as this film. Keitel won an Independent Spirit Award for his performance, and the picture itself has become something of a cult hit. There’s even a pseudo-sequel due out soon, by Werner Herzog of all directors.

The screenplay—written by Ferrara and former model Zoë Lund, who appears briefly onscreen as a hooker—consists of what the simple title suggests: An unnamed New York City lieutenant detective behaves badly and, in the end, wonders if redemption is possible. But it’s not merely bad behavior; Keitel’s character reaches the ultimate lows and then goes even lower. He abuses the authority of his position at every turn, as he’s long since been a monster when the film opens. Married and with several children, he sleeps in his middle-class home on his middle-class couch, awakened by cartoons and the rumbling of his live-in sisters. After dropping off his two boys at school, he gets his fix of cocaine, and he’s ready to start his day.

He goes off to work, where he doesn’t work much at all; rather, he sweats about his money on the World Series game between The Mets and his favorite, The Dodgers. No matter how many times his team loses, he keeps laying his money down, digging himself in deeper with his bookie. The city is filled with crime, some of which he observes complacently while he phones in his bets. He’s winding down after a long-standing addiction to drugs, mostly cocaine and crack, and the occasional shot of heroin, but there’s plenty of booze and prostitutes in his daily routine as well. Nothing puts his body or soul to rest. He seems to writhe with unease—he’s hungry for his next hit, sure, but there’s something more. Whatever demons chase him, they’re gaining ground very quickly.

Is he beyond redemption? That seems to be the question the film asks. Given his deplorable behavior and the complete lack of redeeming qualities shown onscreen, the viewer is hardly capable of lending him sympathy or absolution. In one scene, this failing junkie detective pulls over two Jersey girls out on the town in their dad’s car; he exploits them in a way best not described within this review. In another scene, he breaks up a grocery store robbery; he sends a beat cop off to get the store owner’s statement and meanwhile robs the thieves of their loot. But his redemption rests in the heart of a nun, who is raped by two goons and refuses to name them because she has forgiven them.

If this tortured and abused nun can grant her assailants forgiveness, then perhaps there is a chance for Keitel’s character. Wasted and tired, he sees a hallucination of Christ and screams his sorrows and his frantic cries of despair at the vision. Guilt consumes him, as there’s a part of him that knows everything he’s doing is wrong. In the final scenes, he’s led to the two rapists. Instead of blowing them away as he originally intended, he takes them to a bus station and sets them free. Afterward, his careless gambling has caught up with him and he’s killed by his bookie in the film’s last shot. But in a twisted way, letting two rapists go free grants him some kind of humanity as if carrying out the wishes of the nun, thus the Word of God has brought him a sense of self-sacrificial identification with Christ.

Ferrara’s formal approach echoes the character. The film stock is grainy and the camerawork unstable, which also reflects the shoestring budget. Ferrara’s direction is non-intrusive, capturing what happens with a documentarian’s eye for objective observation. Despite the rating, the film is not pornographic or overtly sexual; not a single scene in the film desires to be “sexy”—rather, Ferrara seeks to expose his subject. What this film is about is the performance, Keitel’s absolute bearing of his character’s soul (and, in one scene, his nude body, presented in its bare humanity). It’s a daring portrayal that strips away human frontiers to reveal the weak and impulsive animal underneath. It’s an exhausting experience for the viewer, and it’s sometimes hard to endure. Few actors have exposed themselves like this.

Harvey Keitel has been giving great performances for years, from his wisecracking pimp in Taxi Driver to the ultra-cool Mr. Wolf in Pulp Fiction. The nearest comparison to his role in Bad Lieutenant is to that in Martin Scorsese’s 1973 masterpiece, Mean Streets. As a street punk riding around New York City and getting into trouble, Keitel’s character in that film weighs his Christian guilt against his behavior, burning his hand over a candle as penance. Once again, Keitel embodies a role wrought by remorse but driven by an insatiable self-destructive streak, two forces that cannot be reconciled and lead to disastrous results, but astonishingly powerful drama.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review