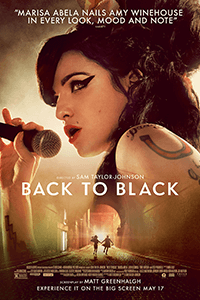

Back to Black

By Brian Eggert |

In Back to Black, Amy Winehouse claims she doesn’t care about fame. Above all else, she wants to be known for “just being me.” And that’s part of the problem, given how the movie interprets her life as a series of tragedies, addictions, and disappointments, albeit capped by a few Grammy awards. Directed by Sam Taylor-Johnson, who conforms to the musician biopic template with maddening banality, the film takes a regressive look at the musician. Winehouse, celebrated for her distinct style that folded jazz and R&B into a soulful sound with a modern, no-bullshit edge, was also a troubled person whose life ended at 27 due to alcohol poisoning. Based on this movie, spending any amount of time with her seems like an insufferable experience, recalling what it’s like to endure Jim Morrison’s interminable behavior in Oliver Stone’s The Doors (1991). Both movies, and many others like them, revel in portraying their subject as an obnoxious addict on a path of such determined self-destruction that the wonderful music they make almost doesn’t make up for their incessant, repetitive antics. Unfortunately, the low points of Amy’s life overshadow her music in Back to Black, leaving us less astounded by the power of her artistry than frustrated by her behavior and resentful of the movie for presenting her this way.

The screenplay by Matt Greenhalgh adheres to the musician’s biopic formula to almost comical degrees. The format has become such a cliché as to deserve parody, most memorably in Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story (2007) and Weird: The Al Yankovic Story (2022). But that hasn’t stopped productions about Freddie Mercury, the N.W.A., Elvis Presley, Aretha Franklin, and Bob Marley from following the basic structure. Most of these movies have the same aspects in common: they each showcase an excellent performance by an actor who inhabits their musician role, though the storytelling often feels sanitized for mass consumption. Even Back to Black, which spends so much time in Winehouse’s inebriated state, plays like the safest way anyone could tell her story. Of course, inspired filmmakers could take this blueprint and make something special out of it. The outline isn’t necessarily the problem; it’s the generic, Wikipedia-article manner in which most movies of this sort adhere to it.

Marisa Abela plays Winehouse in a capable performance that lacks the singer’s unpredictable ticks and the long face that went with her signature beehive. The performance plays like a really good impersonation rather than an embodiment. But at least Abela replicates the distinctive Winehouse sound flawlessly, saving viewers from having to endure the bad lip-syncing customary for musician biopics. In a tight-knit family, where her former singer grandmother (Lesley Manville) and cab-driver father (Eddie Marsan) support her plans to become a singer, Amy quickly lands a deal to record her first album. Then, she meets Blake Fielder-Civil (Jack O’Connell) at a local pub and falls in love, after which she remains locked in a codependent orbit of hard partying, domestic violence, and erratic behavior. In portraying their relationship’s ups and downs, Taylor-Johnson features more than one scene of Amy stumbling home drunk through a dark tunnel to convey her journey into self-destruction. All the while, you can almost smell the cigarettes and vodka wafting off the screen during this grueling endurance test.

Still, Back to Black never feels dangerous or unstable like Winehouse. It’s not a form-follows-function aesthetic, and a more radical treatment may have better captured the tenor of Winehouse’s personal life. Instead, Taylor-Johnson delivers a straightforward-looking movie that aligns with the more old-school aspects of Winehouse. Cinematographer Polly Morgan’s lensing is assured and cohesive throughout, but there’s no strong visual style to distinguish it. Say what you will about Stone’s The Doors, but it captured the volatility of the 1960s, just as Alex Cox’s film Sid and Nancy (1986) evoked the punk scene of the 1970s in formal terms. Here, a choice to immerse the viewer in the sloppiness of Winehouse’s life with a style to match may have been preferable to the generic presentation. However, it’s not surprising that Taylor-Johnson makes her production so accessible; after all, musician biopics have been reliable commercial products for studios. By a distributor’s commercial logic, making a movie’s aesthetic so entrenched that it turns off the audience is a risk to potential profits, even if the uncommercial choice better conveys its subject.

Still, Back to Black never feels dangerous or unstable like Winehouse. It’s not a form-follows-function aesthetic, and a more radical treatment may have better captured the tenor of Winehouse’s personal life. Instead, Taylor-Johnson delivers a straightforward-looking movie that aligns with the more old-school aspects of Winehouse. Cinematographer Polly Morgan’s lensing is assured and cohesive throughout, but there’s no strong visual style to distinguish it. Say what you will about Stone’s The Doors, but it captured the volatility of the 1960s, just as Alex Cox’s film Sid and Nancy (1986) evoked the punk scene of the 1970s in formal terms. Here, a choice to immerse the viewer in the sloppiness of Winehouse’s life with a style to match may have been preferable to the generic presentation. However, it’s not surprising that Taylor-Johnson makes her production so accessible; after all, musician biopics have been reliable commercial products for studios. By a distributor’s commercial logic, making a movie’s aesthetic so entrenched that it turns off the audience is a risk to potential profits, even if the uncommercial choice better conveys its subject.

The script has similar problems. Because dull movies always love to provide answers to unknowable questions, Back to Black suggests that the driving force of Winehouse’s downward spiral is her lack of a child. It’s a reductive take on a woman’s life and not reinforced by a wealth of biographical evidence since anyone afflicted by alcoholism, crack addiction, bulimia, and anger issues probably has more going on than just a fervent desire to become a wife and mother. After all, many of Winehouse’s difficulties began in her late teens, when she first started to become a star, so perhaps the blame belongs on the music industry, her reckless youth, or some other unknowable factor at play. But rather than confront the audience with an equivocation, Taylor-Johnson and Greenhalgh invent an accessible key to unlock this enigma. Her domestic aspirations function like a salve, suggesting to viewers that Winehouse must be a good person deep down because she had these desires to lead a traditional life. However, the movie would have been braver to suggest that, perhaps, Winehouse was simply too complicated to understand, and out of that complexity arose her music.

Ultimately, the movie peaks for Winehouse with her multiple Grammy wins, suggesting they’re her premier life achievement, yet, upon reflection, judging a person’s life by the awards they compiled is downright depressing. But then, this is a miserable way to spend two hours. Back to Black weighs the viewer down over the first hour before becoming a slog with more than an hour to go. By the end, you feel exhausted, having been put through a gauntlet of erratic behavior, emotional turmoil, and lack of self-examination. Aside from a few admirable supporting performances—Manville and Marsan make everything better—and a breakout role for Abela, the movie doesn’t offer new insights or ways of thinking about Winehouse’s legacy. It’s not even a good showcase of her music, featuring only a handful of songs that amount to a greatest hits album. Too miserable for general audiences and too surface-level for discerning viewers, Back to Black is suited for apologist fans only.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review