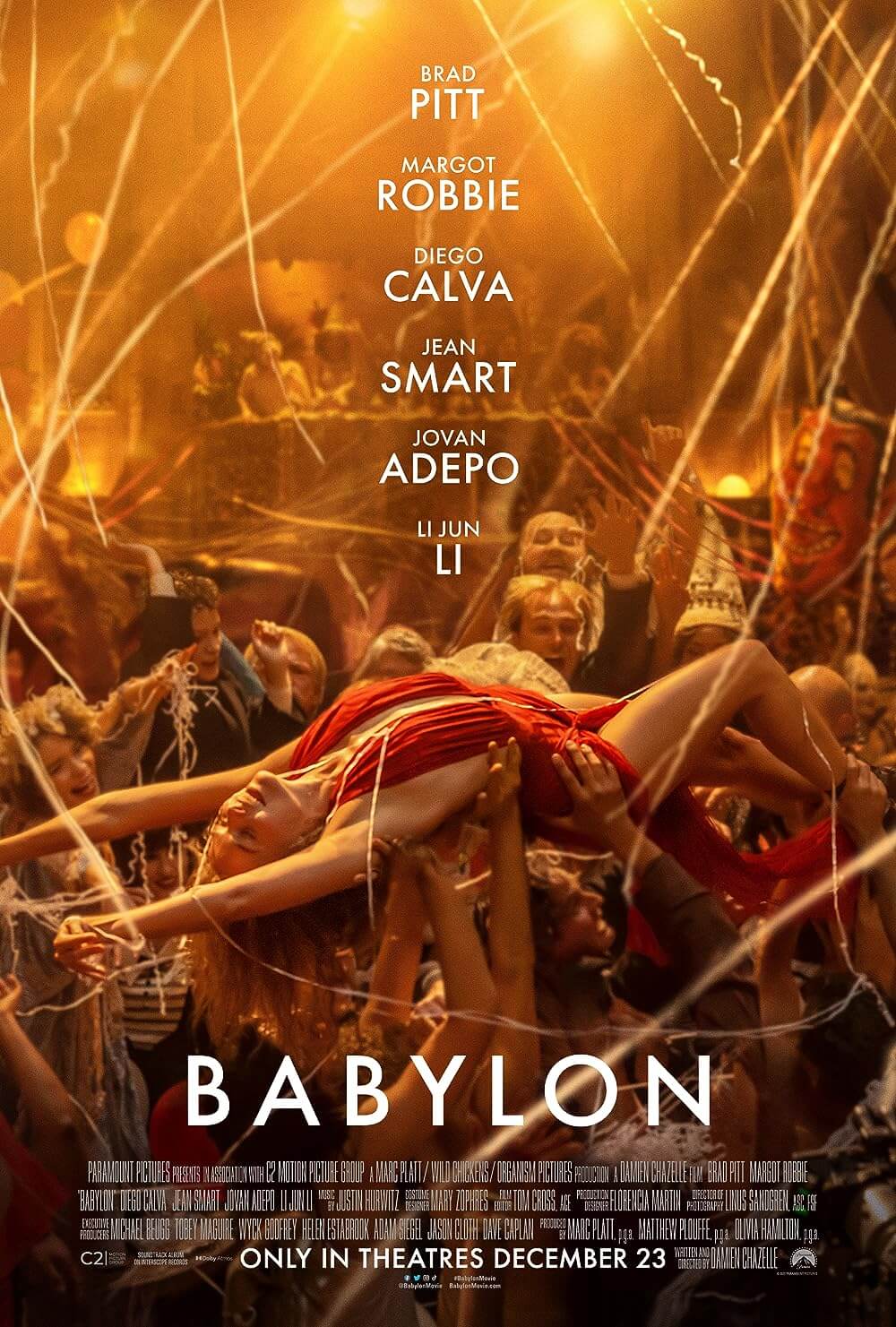

Babylon

By Brian Eggert |

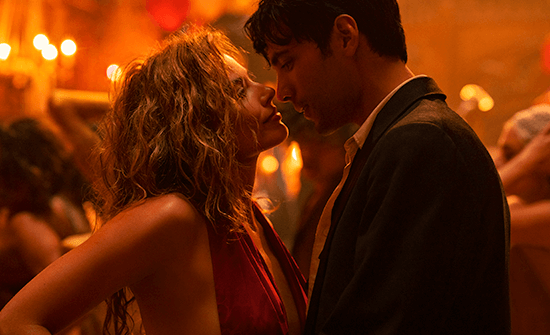

One of the first sights in Damien Chazelle’s Babylon is an elephant’s unpuckered anus blasting out gooey chunks of nervous excrement onto two unfortunate men attempting to push the animal up a hill. At the top of the hill awaits a Xanadu-like mansion owned by a Hollywood executive, an epic party spot visited by screen stars, copulating dancers, a dwarf on a pogo-penis, and a guy named “Piggy” who likes golden showers. They revel amid streamers, a killer jazz band, an endless supply of alcohol, and a drug room with mounds of cocaine and every other illegal substance you can imagine. Eventually, the elephant makes an appearance, but only to distract from an overdosing girl who must be quietly removed from the premises. Chazelle’s madcap film takes a kaleidoscopic journey through Hollywood’s unbridled silent era and its famously debased party atmosphere. The lunacy begins in the roaring ‘20s, long before the Production Code self-regulated morals onto Hollywood products. The trade papers, celebrity magazines, and studio promotional wizards may call Tinseltown “the most magical place in the world,” but its reputation differs from reality. As countless dramas about Hollywood contend, the industry processes young ingenues and wannabes like a meat grinder. And those lucky enough to survive are usually forgotten.

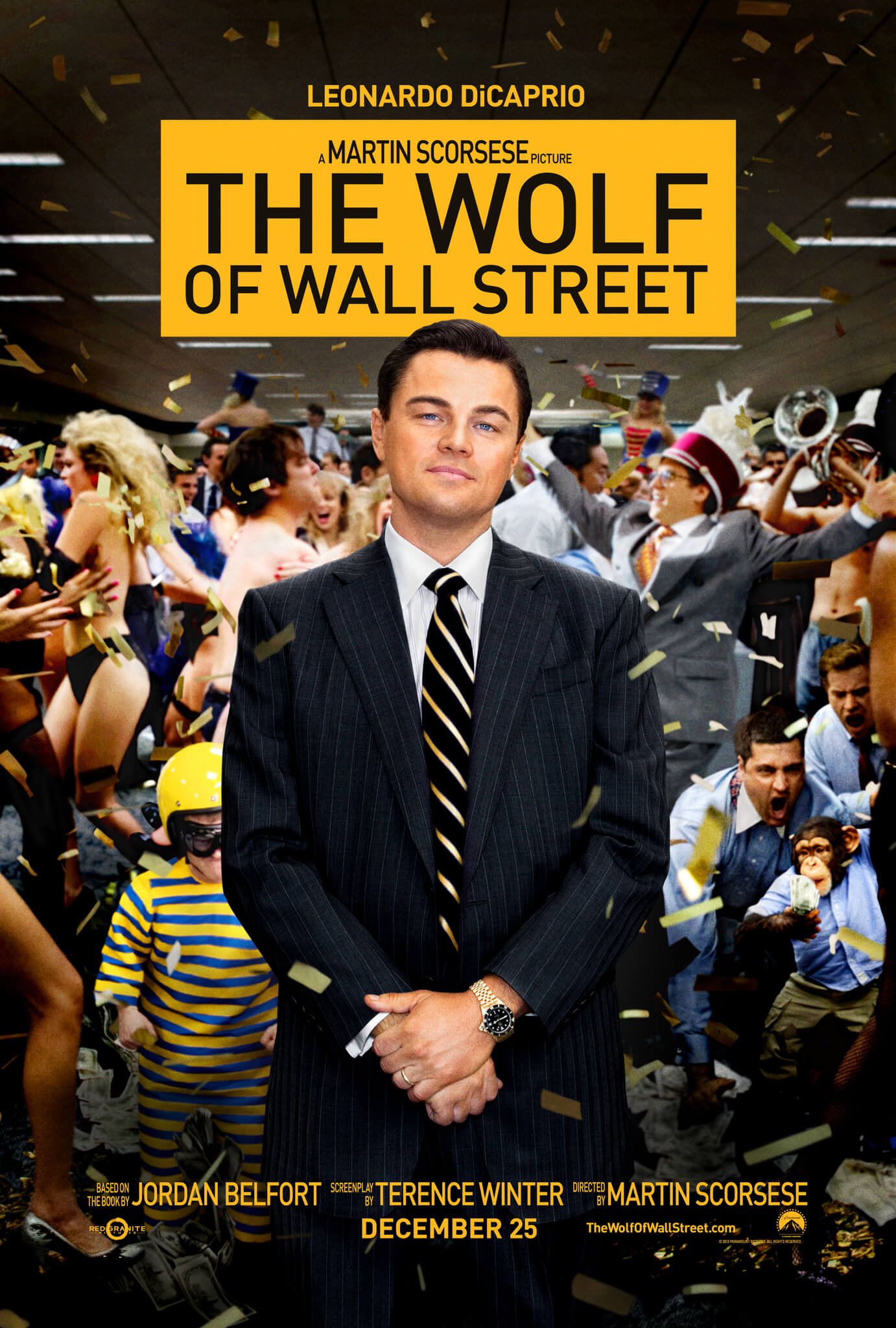

Chazelles’s film, his most ambitious to date, looks at the entertainment industry through a similar lens as Kenneth Anger’s salacious 1959 book, Hollywood Babylon, which exposed scandals and perpetuated urban legends about Hollywood’s wild adolescence. And sure enough, Chazelle’s screenplay alludes to enough real-life figures from when the Silent Era transitioned into Talkies to delight anyone familiar. Narratively, the director adopts a similar approach to Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), boasting an epic-sized production of rampant indulgence. It’s largely to comic effect for the first two hours, until the last third comments on its many immodesties as doomed and corrupt. Ken Russell may have already supplied a portrait of early Hollywood hedonism and celebrity with Valentino (1977), but Chazelle uses the setting to replay themes found in his Whiplash (2014), La La Land (2016), and First Man (2018). He follows a cross-section of professionals, up-and-comers, and those desperate to become stars through any amount of hard work or self-debasement necessary. While the backdrop may be teeming with excesses and copious period details, it’s a variation on a theme for Chazelle, who once more concerns himself with committed artists.

Among them is silent movie star Jack Conrad (Brad Pitt), who maintains his iconic status while contending with a drinking problem and a growing list of ex-wives, not to mention the looming reality of irrelevance. Lowly assistant Manny Torres (Diego Calva), the recipient of pachyderm feces in the opening, serves as a beleaguered gopher to the Hollywood elite but soon realizes his dream of becoming a filmmaker. Nellie LaRoy (Margot Robbie, a force of nature throughout) is a fearless and insatiable country girl who arrives in Los Angeles with raw talent and no limits. Joined by her huckster father (Eric Roberts), Nellie is just as determined to become a star as Mia Goth in Pearl. More peripherally, Sydney Palmer (Jovan Adepo) is a Black jazz trumpeter who discovers that Hollywood only wants to exploit his talent and race, while singer Lady Fay Zhu (Li Jun Li) finds her brand of risqué sexuality frowned upon as moral groups take aim at Hollywood and call for censorship in the movies. All the while, tabloid journalist Elinor St. John (Jean Smart) writes about them all from the sidelines.

Throughout Babylon, there’s a persistent sense that Chazelle is having a blast and experimenting at every turn. Linus Sandgren, the cinematographer on the director’s last two features, concocts elaborate extended takes that maneuver through euphoric parties and frantic movie sets. Chazelle’s use of whip pans and cracking flash bulbs draw from Scorsese’s technique for creating momentum, while editor Tom Cross maintains an exhilarating pace, accompanied by Justin Hurwitz’s propulsive score, especially in the early scenes that follow each character’s emergence or decline. There’s a breathless sequence on the set of Conrad’s latest costume epic, directed by a volatile German (Spike Jonze) reminiscent of Erich von Stroheim. The production employs hundreds of extras, some of whom die in the unregulated production alongside horses, well before unions and the American Humane Association started monitoring human and animal safety on movie sets. Every camera has broken, and they’re losing the light, so Manny must race into town to rent another camera. Manny pulls through, and the chaotic rush to capture the final shot results in a serendipitous moment caught on camera, proving what Orson Welles said about moviemaking—that it’s about presiding over accidents.

Throughout Babylon, there’s a persistent sense that Chazelle is having a blast and experimenting at every turn. Linus Sandgren, the cinematographer on the director’s last two features, concocts elaborate extended takes that maneuver through euphoric parties and frantic movie sets. Chazelle’s use of whip pans and cracking flash bulbs draw from Scorsese’s technique for creating momentum, while editor Tom Cross maintains an exhilarating pace, accompanied by Justin Hurwitz’s propulsive score, especially in the early scenes that follow each character’s emergence or decline. There’s a breathless sequence on the set of Conrad’s latest costume epic, directed by a volatile German (Spike Jonze) reminiscent of Erich von Stroheim. The production employs hundreds of extras, some of whom die in the unregulated production alongside horses, well before unions and the American Humane Association started monitoring human and animal safety on movie sets. Every camera has broken, and they’re losing the light, so Manny must race into town to rent another camera. Manny pulls through, and the chaotic rush to capture the final shot results in a serendipitous moment caught on camera, proving what Orson Welles said about moviemaking—that it’s about presiding over accidents.

At the same time, it was an era where women directors weren’t so uncommon, and filmmakers openly perpetuated racial stereotypes—and perhaps created a few. Chazelle bobs and weaves through the production grounds of Kinescope, headed by executive Don Wallach (Jeff Garlin), and spies various shoots underway—some that test the boundaries of acceptable representation. But a hilariously entertaining sequence finds Nellie on her first movie set, under the direction of Ruth Adler (Olivia Hamilton). Chazelle casts Robbie’s doppelgänger Samara Weaving as Nellie’s established competition, a meta-commentary on the cutthroat business when Nellie outshines her costar. Nellie’s fearlessness and bawdy behavior make her a star and earn her the nickname “Wild Child” by the press. But like Conrad, her celebrity is tested in 1927 with the emergence of sound pictures. Chazelle borrows a similar playbook from Singin’ in the Rain (1952), wherein the filmmakers struggle to capture sound for tomorrow’s audience with crude equipment under riotously brutal conditions—hot lights and temperamental recording devices. A slapstick sequence centered on the filming of a rather innocuous scene in a dull programmer becomes a nerve-racking ordeal for all involved, particularly Adler’s stressed assistant director (P.J. Byrne).

About halfway through the proceedings, the characters realize that Hollywood is changing. But Conrad won’t make the same adjustment to sound as Don Lockwood in Singin’ in the Rain; his star dims, signaled by the grim fate of his producer friend (Lucas Haas). Pitt is excellent in his early scenes as a charismatic actor, while his aching humanity and pride as an artist emerges in the last third. Although Conrad recognizes that he’s past his prime, he defends his devotion to motion pictures, giving a passionate speech that condemns how New York elites, such as his stage actor wife (Katherine Waterston), look down their noses at his entertainment for the masses. Chazelle’s mournful undercurrent echoes Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019), which shares several similarities to Babylon: Both star Pitt and Robbie. Both films feature a shot with Robbie’s character overjoyed at seeing herself onscreen. Both also portray Hollywood at a liberated time. But Chazelle’s film doesn’t take a detour into historical revisionism, as Tarantino imagines a world in which Sharon Tate was never murdered by the Manson family, and therefore Hollywood’s 1960s optimism never faded. In Babylon, the catalyst of sound marks an artistic paradigm shift that may have led to a creative boom for many, but it leaves the film’s characters in its wake.

To be sure, the new Hollywood morality that followed sound reframes Nellie’s unrelenting pleasure-seeking and lack of refinement. She is slutshamed, labeled as trash, and ousted by the increasingly sanctimonious press. Manny does his best to help Nellie by arranging lessons in elocution and upper-class etiquette, but she’s too unfiltered to fit among the elitist class. It’s a reality made clear during an over-the-top, vomitous encounter with William Randolph Hearst—a silly moment that feels overly farcical, even for Babylon. Eventually, Nellie’s gambling and drug addiction lead to an all-time-low sequence, recalling the paranoid, cocaine-addled scenes in Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990), where Ray Liotta tries to manage cooking pasta sauce, dodging helicopters, and moving drugs in the same afternoon. In Chazelle’s version, Manny enlists the help of Hollywood’s resident Dr. Feelgood, known as The Count (Rory Scovel), to help clear Nellie’s debt. The sequence finds them in the company of a powerful freak (Tobey Maguire, looking undead) who insists they join him at “LA’s last real party.” Four levels down into a subterranean hellscape of human trafficking, geek shows, and chained beasts, Manny and The Count resolve they have seen too much of Hollywood.

To be sure, the new Hollywood morality that followed sound reframes Nellie’s unrelenting pleasure-seeking and lack of refinement. She is slutshamed, labeled as trash, and ousted by the increasingly sanctimonious press. Manny does his best to help Nellie by arranging lessons in elocution and upper-class etiquette, but she’s too unfiltered to fit among the elitist class. It’s a reality made clear during an over-the-top, vomitous encounter with William Randolph Hearst—a silly moment that feels overly farcical, even for Babylon. Eventually, Nellie’s gambling and drug addiction lead to an all-time-low sequence, recalling the paranoid, cocaine-addled scenes in Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990), where Ray Liotta tries to manage cooking pasta sauce, dodging helicopters, and moving drugs in the same afternoon. In Chazelle’s version, Manny enlists the help of Hollywood’s resident Dr. Feelgood, known as The Count (Rory Scovel), to help clear Nellie’s debt. The sequence finds them in the company of a powerful freak (Tobey Maguire, looking undead) who insists they join him at “LA’s last real party.” Four levels down into a subterranean hellscape of human trafficking, geek shows, and chained beasts, Manny and The Count resolve they have seen too much of Hollywood.

Exhausting though it may seem, the film’s three-hour-and-nine-minute runtime doesn’t overstay its welcome, not even after the relentless array of partying, persistent debauchery, rogue subplots, and the surreal journey into a depraved underworld. It’s deliriously entertaining. That is, until the final coda. With a few minutes of screentime left, Chazelle leaps ahead to 1952. By this time, most of the characters have either died or faded into obscurity. Manny returns to Hollywood for the first time in years and catches a matinee screening of Singin’ in the Rain (what else?). Besides mirroring the MGM musical, the film’s story unfolds against the industry’s move to Talkies, and it’s an obvious inspiration for Chazelle throughout Babylon, and calling attention to it only cheapens the allusion. Worse, Chazelle then deploys a rhapsodic, jazzlike montage that celebrates the entire history of cinema, complete with movie clips intercut with inky colored swirls, creating psychedelic shapes. Amid the ungainly montage, his transitions to clips from Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) to Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) to The Matrix (1999) suggest a rather narrow outlook of special FX-laden entertainment, even if he does end the sequence with the most pointed juxtaposition: a clip from Avatar (2009) followed by one from Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966). After flashing back to the bacchanalia from the opening and a few nostalgic moments throughout the film, Chazelle ends Babylon on a deflated and sloppy note.

Indeed, the end sequence stops the film dead in its tracks, almost derailing everything that came before, messy though it is. Even so, that the montage exists at all is confirmation that Babylon is, at the very least, Chazelle’s personal expression and not a studio-crafted commercial product. Still, an earlier moment, such as a scene where Nellie disappears into a shadow, may have been a better place to end. Regardless of how much the last section sours what came before, Chazelle’s film is an admirably ambitious production that does for pre-sound Hollywood what Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights (1997) did for the porn industry. And during Conrad’s scenes where he laments the end of Hollywood as he knew it, tenderly conveyed by Pitt, one cannot help but wonder whether Chazelle is making the same remarks about Hollywood today. Perhaps that jarring cut from Avatar to Persona is meant to emphasize how rarely films today have artistic ambitions. Then again, maybe his story acknowledges that film hasn’t changed much in the last century, and it’s always been an unholy marriage between art and commerce, creation and exploitation. Or maybe (and this is my belief), Chazelle points out that cinema is more often about entertaining the masses, whereas art cinema represents a rather small portion of filmmaking, but both modes have importance.

Similar to Scorsese and Anderson’s referenced films, Babylon recognizes that the industry in question remains fluid, inhabited by people who hang on the ride and indulge while they can. As Smart’s Elinor St. John observes, “it’s the idea” of Hollywood that endures, while the reality is a series of wild parties, tragic stories, forgotten names, and iconic images. Some have been immortalized to celluloid, and others have disappeared forever. Chazelle’s script never approaches subtlety, even when asking whether all the collateral damage is worth the resulting art—his answer, surely, is a resounding “Yes!” Inevitably, this long and untidy film that often plays like an orgy of excess will seem repulsive and amoral to some, leading to conversations about whether representation means an endorsement (which raises other questions about media literacy). But the director both recognizes the appeal of those uninhibited days and acknowledges how such freedoms came with reckless and incautious behavior, which sometimes results in the most memorable art. Babylon captures the highs and lows with a formal bravado that Chazelle’s fans will no doubt expect and not soon forget. The film makes bold swings that don’t always land, yet it’s not easily dismissable as a sensationalistic, ambitiously crammed, and wonderfully exhausting portrait of Hollywood.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review