Babygirl

By Brian Eggert |

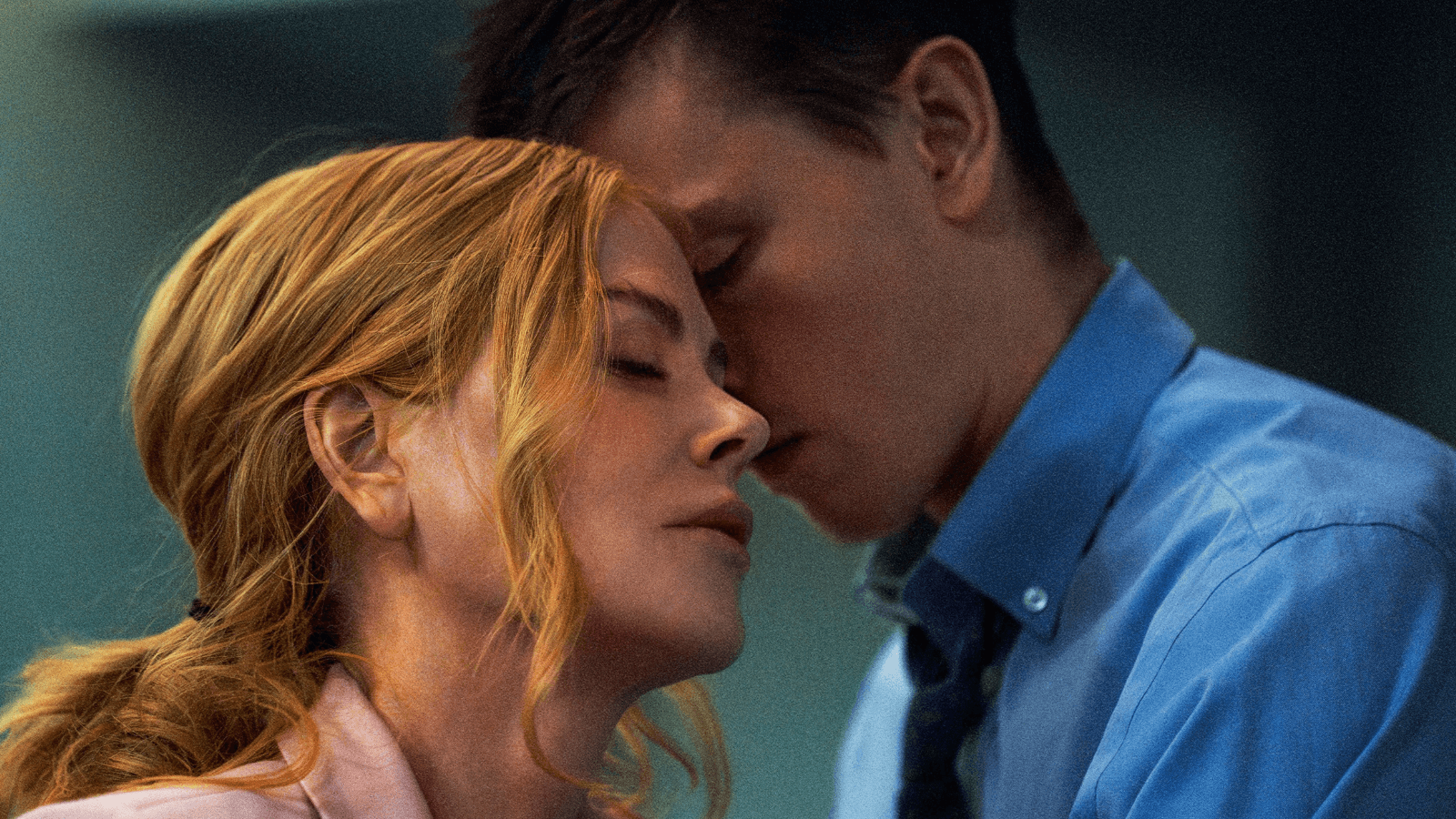

Bookended by orgasms, the first one faked, the latter presumably genuine, Babygirl tells the story of a top female executive exploring sexual and power dynamics. Writer-director Halina Reijn’s drama features Nicole Kidman’s showy performance as Romy Mathis, the CEO of Tensile, a warehouse robotics efficiency outfit. A workaholic and phone addict, Romy has an idyllic life on the surface: a playwright husband named Jacob (Antonio Banderas), two teen daughters, an apartment in the city, a lavish country house, and a position many of her colleagues admire. While Romy thrives on control professionally, she secretly yearns to give up her power to someone else. Perhaps giving power away in a controlled situation will relieve her everyday pressures to maintain that control. Romy has been hiding this curiosity from Jacob, leaving her split between living a so-called respectable but repressed life and wanting to explore what she deems to be “dark” and “obscene” desires. When she launches into a dom-sub affair with an office intern, Samuel (Harris Dickinson), she risks everything for sexual gratification. That her family and career hang in the balance is part of the pleasure.

Refreshingly free of moralizing by the filmmakers, Babygirl sets out in character study mode and doesn’t seem interested in pushing the boundaries of onscreen sex. Despite its mechanical sex scenes and occasionally blunt writing, it’s an improvement on the other major BDSM movie involving very wealthy people, Fifty Shades of Grey (2015). Reijn is a better writer than E. L. James and captures her protagonist’s inner life—though, she leaves many supporting roles underdeveloped. Romy is the sort of character who invites armchair psychoanalysis, and undoubtedly, some psychology major will write an interesting paper about her behavior. She first spies Samuel calming a loose dog. Something about how he commands the animal turns her on, and from that moment, she’s drawn to him, desperate to be tamed like the dog. Sensing her interest, Samuel sizes her up after minor challenges to her authority. Then he signs up for her company’s mentorship program, becoming Romy’s mentee in a relationship that leaves their power dynamic in disarray and Romy thoroughly confused by her feelings.

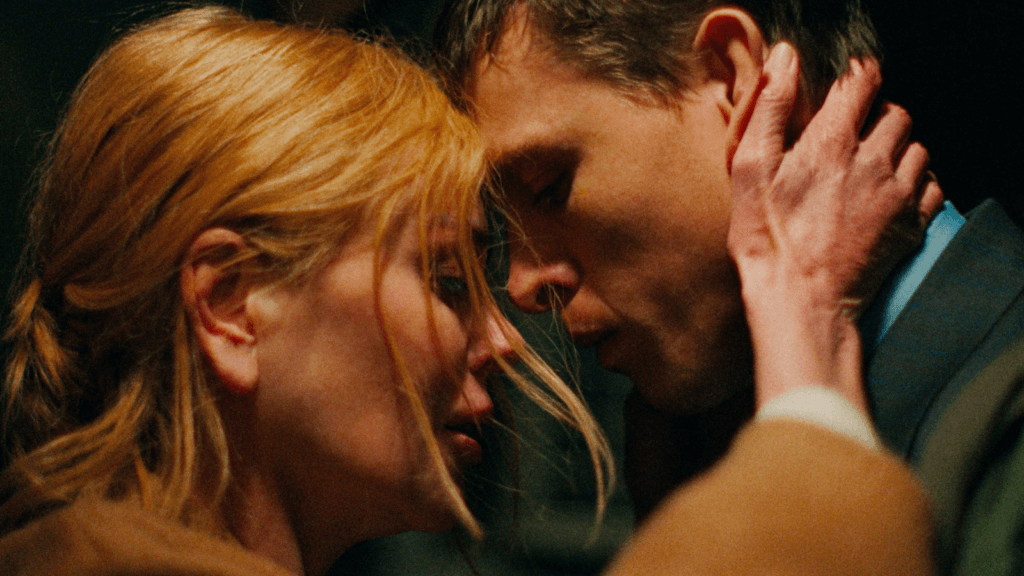

Reijn’s script grapples with a lot. The director of Bodies Bodies Bodies (2022) tackles a necessary conversation about sex positivity and not yucking other people’s yums. Her writing is sympathetic to Romy’s desire, yet it’s not blind to how what happens behind closed doors can impact other aspects of life. For starters, there’s Romy’s family. Married for 19 years, she remains too ashamed to speak to Jacob about what she wants, in part because he seems more interested in conventional intimacy, such as eye contact. At one point, Romy literally hides under the covers to tell Jacob what she wants, and even then, she backs down. By introducing desires into their marriage that some part of her believes are “wrong,” she worries they may disrupt their outwardly happy appearance. Romy’s issues with honest communication also extend to the office, whereshe plays a volatile game, particularly with her ambitious assistant, Esme (Sophie Wilde, from Talk to Me). Reijn confronts the consequences of workplace affairs, particularly concerning the responsibilities of women in power positions.

While Babygirl sets up a dangerous situation for Romy, Reijn isn’t interested in punishing the character for her choices. “It’s a positive to be vulnerable,” says a marketing director to Romy, “not a negative.” To be sure, the sex between Romy and Samuel has a kind of openness, humor, and honesty to it. They laugh and have fun while figuring out what they can do for each other. It might even be touching if Romy hadn’t betrayed her marriage or if Samuel wasn’t such a nonentity. Indeed, Reijn’s focus on Romy means Samuel is a nothing character who enters her life, unlocks her sexuality, and then disappears all too conveniently. Unfortunately, Reijn’s script also makes a passing reference to Romy’s upbringing in “communes and cults,” which supplies a vague and unexplained hint that her desires result from some childhood trauma, which de-normalizes them. That seems to go against the film’s message about sexuality, captured in Samuel’s observation: “We’re like two children playing, and that’s natural.”

For all of its erotic flair, Reijn’s script too often intellectualizes what might be more effective in emotionally driven scenes. Later in the film, there’s an undisguised conversation about whether female masochism is a male construct or if that’s a “dated” idea. Samuel makes observations such as, “I think you like to be told what to do” and “It’s about giving and taking power,” which put too fine a point on what the audience might have intuited from a dramatic scene. These open discussions, which register like a group therapy session, sit on the surface in the dialogue, whereas the story was readable enough without such points being spelled out for us. A somewhat more subtle, tender subplot involves Romy’s relationship with her queer daughter, Isabel (Esther McGregor), who’s more in tune with her sexuality than her mother. This underscores the notion that younger generations are more open about their sexuality, whereas older generations have been repressed by social, religious, and political factors—all without the dialogue underlining it.

Set against the holiday season, Reijn’s second film for A24 hopes to be a salacious affair reminiscent of Kidman’s appearance in the Christmastime favorite Eyes Wide Shut (1999). Much of the buzz around Babygirl involves its sex scenes, with words on the movie poster such as “raw” and “fearless” to describe Kidman’s performance. The 57-year-old actor spends a lot of time on all fours, undressing, getting pushed up against walls, and drinking milk (an unexplained kink for both), while the soundtrack blares amusing choices including “Never Tear Us Apart” by INXS and the awkward “Father Figure” by George Michael. It’s refreshing to see a middle-aged woman’s sexuality portrayed in such frank terms, but one gets the impression that Reijn is attempting to shock her viewers—though, the sex scenes are far from scandalizing and more psychological. The one true, passionate, even erotic moment occurs when Romy has her first orgasm with Samuel, who knows instinctively to lay her flat on her stomach, the same way she masturbates earlier in the film. Kidman delivers a convincing orgasm performance: it doesn’t look or sound like a movie orgasm; it’s messy and uninhibited.

Reijn’s formal approach is thoughtful if overt. The score by Cristobal Tapia de Veer often consists of breathy and vocalized notes, as though recorded mid-coitus. Much of the film is shot with crisp cinematography by Jasper Wolf, who deploys no end of shallow focus to convey how Romy has lost perspective on everything else around her. And while Kidman has received much attention, Banderas is excellent as a genial husband whose open-hearted and honest reaction to his partner’s betrayal steals the movie. Babygirl is about a complex and enduringly fascinating main character, but its dull literalization of every theme in the dialogue renders the drama inert. There’s enough to Romy to build an intriguing case study, yet the psychological motivations seldom feel backed by our emotional involvement. Worse, Reijn delivers an overly tidy, optimistic ending that finds Romy in control of when she has power and when she doesn’t, not to mention her marriage repaired and desires fulfilled. The journey to controlling one’s power, along with honest communication about desire, is the central message of Babygirl. But the resolution feels far too prescribed and convenient, given the messy situation, leaving the film’s overstated themes to be the driving force, not the characters.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review