Babies

By Brian Eggert |

One of the best, most endearing, and flat-out funniest moments in Babies is when French documentarian Thomas Balmès cuts between the delight of one infant ingesting toilet paper and another’s utter frustration with her toy. As the one prattles on in his gurgling baby chatter, thrilled in unraveling a roll of bath tissue, the other cries in frustration at her wooden rod that’s meant to go through a hole in a disc. She tries to assemble the two pieces, but they slide apart, which sends her reeling into a convulsing, absurd tantrum. She stops crying for a moment, picks up a nearby book, realizes she doesn’t understand this either and flops into another outburst. Meanwhile, the other child couldn’t be more content burbling on with a mouthful of toilet paper.

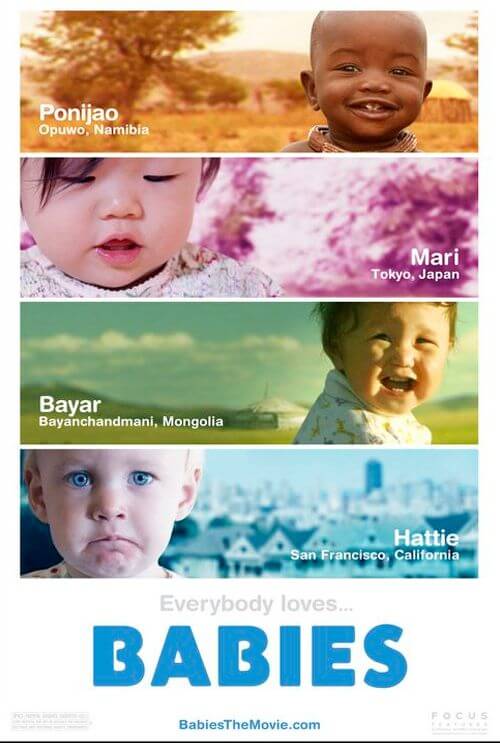

Shot over a year in various sections of the globe, Balmès and his crew captured many moments such as this one and presented them in a rather simplistic, rather ingenious form. Without narration or explication, or even outward parental advice of any kind, the documentary proceeds with just images, showing us four baby subjects as they progress from delivery to their first birthday. From the dry plains of Namibia to the fertile grasslands of Mongolia, from the metropolis of Tokyo to the New Age haven of San Francisco, the filmmakers present four sets of parents and their newborns. Bayarjargal (Mongolia), Ponijao (Africa), Mari (Japan), and Hattie (California) will share little in common when they’re all grown up, but as we see in this first year, despite their geographical and cultural distance, they’re pretty much the same.

Each of the children has seemingly distinct personalities, some more curious than others, each developing at their own pace. Ponijao, for example, plays at simulating her mother’s food preparation duties by grinding clumps of sand between two rocks; she also develops physically faster than the other infants, despite living in what’s called a “third world” country. She’s the first one to walk on her own, and even nearly masters the art of balancing a can on her head in the course of the film. Bayar, meanwhile, is the last to walk, but the eventual happening is all the more momentous for it. Surrounded by technology, Mari discovers that gorillas and tigers at the Tokyo Zoo frighten her. Hattie is likewise frightened by her father’s hippie parent circle singing “the Earth is our mother,” so much so that she gets up and heads for the door.

There are no subtitles on this film, so unless you happen to speak an impressive array of languages, there’s no telling exactly what these parents are saying to their children. Although, we can imagine. Every parent seems to utter the same phrases of affection or teaching to their child in the same tone of voice. When one parent says something and the child attempts to repeat it but doesn’t quite get it right, and the parent laughs, but the child looks clueless, this does not need clarification. Even if we don’t understand the words themselves, we intrinsically understand the moment. And, void of voice-over narration that might bring an over-explanatory purpose to what we’re seeing, the film gets its point across.

Some (judgmental) audiences might find themselves concerned, even shocked at first at the diversity of parenting styles presented. As the Namibian mother wipes her daughter’s bottom on her knee and then cleans her knee with a bare cob of corn, Western audiences might recoil. Then again, no doubt a Mongolian viewer, situated on peaceful fields of green, would cringe at the chaotic city environment of Tokyo, or even that of San Francisco—they might ask, do infants need access to cell phones and computers? What becomes evident is that no matter the parenting style, the babies develop at the same pace. As babies, regardless of our country of origin, we all start out the same. We all coo in the same manner. We all smile and struggle to walk. We all try to speak and sometimes do. And we all cry. A lot.

It’s this transcendent message that the film communicates through straightforward pictures. And yet, such basic displays of human existence would never work with a movie called “Teenagers” or “Seniors”, because as we grow, the relevant humanity in us becomes more difficult to identify. Culture destroys our alikeness. And so, even if you don’t “like” babies, you’ll like Babies. You must have a heart of stone not to. There’s much joy here, enough to make this film, which at 79 minutes is barely feature-length, well worth your time. The inherent cuteness and certain peculiarity of the subjects are only outdone by the film’s profound demonstrations of discovery and love, and the basic components of humanity shared the world over.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review