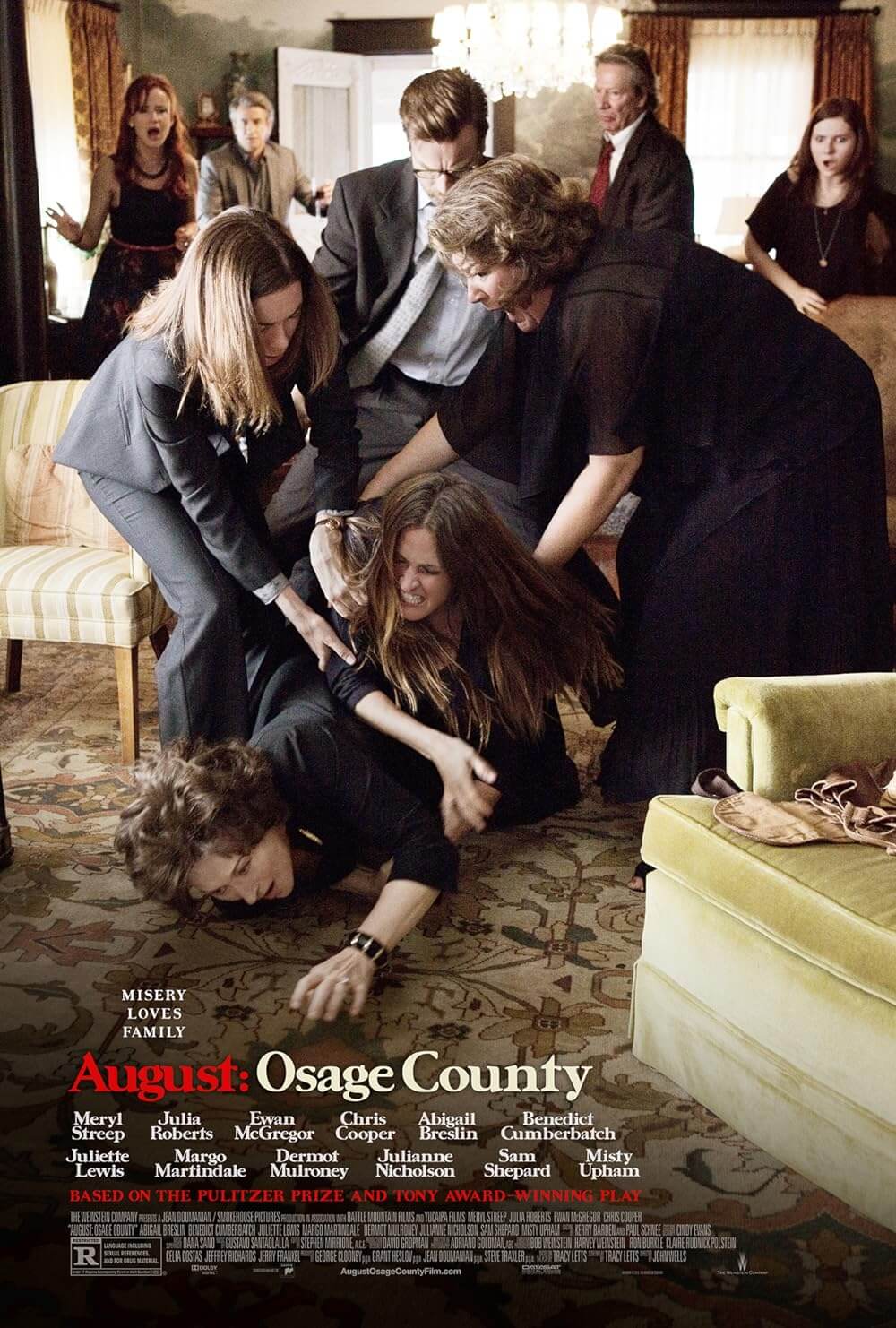

August: Osage County

By Brian Eggert |

“Thank God we can’t tell the future. We’d never get out of bed,” says one character in August: Osage County, an adaptation of playwright Tracy Letts’ Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award-winning Broadway stunner from 2008. Knowing Letts’ previous stage-to-film adaptations, audiences might be afraid for their immediate future during the film, if only because Letts’ tendency to explore damaged and often deranged characters has already resulted in two outrageous film adaptations. Consider the shockingly disturbed yet needy pair in Bug who dream up imaginary pests to remove from their skin, or consider the family of trailer trash schemers in Killer Joe and their nasty appetites (not excluding a fellated chicken drumstick), both films directed to perfection by William Friedkin. Rest assured, nothing so gristly or grotesque exists on the surface of the Weinstein Company’s release of August: Osage County, director John Wells’ faithful film adapted for the screen by Letts.

Nevertheless, the film has no shortage of Letts-brand themes, including acerbic dialogue, hard-flung insults, pedophilia, and a hint of incest. It’s all wrapped up in a meaty, deliciously consumable package that reflects the styles of Tennessee Williams, Eugene O’Neill, and Arthur Miller, and contains an ensemble that offers uniformly Oscar-caliber acting. Wells, whose one other feature was 2010’s unemployment drama The Company Men, delivers a straightforward production in which the material gestates and the performers shine. Set on the sun-bleached Oklahoma plains, the story centers on the Weston family. Their home resides in the middle of nowhere, the perfect breeding ground for the kind of dysfunction on display. “This is the Plains,” another character remarks. “A state of mind… Some spiritual affliction, like the blues.” Letts often isolates his characters in an environment where they fester and rot around one another, the best and worst (but mostly worst) parts of them exposed in larger-than-life spectacle.

Poet and lately a scholarly alcoholic, Weston patriarch Beverly (Sam Shepard) quotes T.S. Elliot when he tells Johnna (Misty Upham), the new Native American caretaker he’s hired for his ill wife, “Life is very long.” Bev soon disappears and, in a short time, turns up dead, having killed himself in a river, leaving his cancer-addled, pill-popping, acid-tongued widow Violet (Meryl Streep) to weep and shout her sorrows. “The punch line,” as Bev explains early on, is that Violet has cancer of the mouth (one of Letts’ more obvious symbolic flourishes), which doesn’t prevent Vi from spewing her wicked truth-telling once Bev’s disappearance and subsequent funeral serves as a makeshift family reunion. The drug-addicted Vi can hardly take herself down from her matriarchal cross long enough to welcome her three girls back into their childhood home, and when they arrive here insistence and seemingly earned right to speak unabashed truth explodes into door-slamming and plate-throwing madness.

Eldest child Barbara (Julia Roberts) arrives with her rebellious teenage daughter (Abigail Breslin) and estranged husband (Ewan McGregor) in tow, facing the scary possibility that she’s almost as stubborn and universally despised as her own mother. The youngest, the ditzy Karen (Juliette Lewis), shows up from Florida with her shady businessman fiancé (Dermot Mulroney) and pronounces her happiness with their planned honeymoon escape to Belize. The middle child Ivy (Julianne Nicholson) has been home taking care of her ailing mother, yet harbors a secret in her ongoing love affair with their dim-witted yet sweet-hearted first cousin “Little” Charles (Benedict Cumberbatch)—son of their headstrong aunt Mattie Fae (Margo Martindale) and pothead uncle Charles (Chris Cooper). Put all of these family members in a room, say, after a funeral and a few drinks, and the scene explodes into unparalleled histrionics that showcase the quality of both Letts’ writing and the chosen cast.

The standout, of course, is Streep’s interpretation of Vi, sounding off under oversized glasses and a dark wig to hide the character’s patchy, grayed-out, post-chemo hair. Vi takes pleasure in her meanness, pointing out with a blazing finger everyone’s shortcomings and best-kept secrets, though she defends her callousness as simple truth-telling. Streep is truly something to behold here, and just when you might condemn her for a scene of overacting, her character surprises us with some subtle piece of humanity—if only to once again shock us with Vi’s awfulness. Just barely keeping up is Roberts, who’s never been so good. Viewers may have a hard time swallowing yet another role where Roberts endures the rigors of a hard life only to find her indomitable spirit, but in truth, her performance is startlingly good, particularly during the post-funeral dinner scene where the film’s dramatics reach their height. But then, the entire ensemble deserves recognition, as there’s not a single false note in the bunch.

Wells and Letts haven’t transformed the play in any drastic way for its translation to cinema, save for reducing its runtime by an hour and omitting its two intermissions. As the film unfurls in exaggerated gestures and endless in-fighting amid the family, it’s primarily contained within the Weston home, with cinematographer Adriano Goldman’s Oklahoma location shooting providing a naturally lit, heat-ridden air. What Wells hasn’t done is eliminate the traces of theater from his film; a number of scenes feel stagey and are better suited for theater, reminding us the material was based on a play. Similarly, the acting occasionally proves so pronounced that the viewer is taken out of the production to reflect on the sheer grandiosity of the performances, namely those of Streep and Roberts. But these are minor criticisms. In the realm of performance-driven plays on film, August: Osage County is vital, if over-the-top, and heightened by its star-studded appeal and prestige as an award-worthy drama.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review