Atomic Blonde

By Brian Eggert |

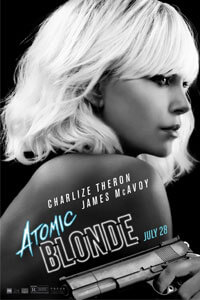

“Everyone you come in contact with dies,” says one character to Lorraine Broughton, the platinum-haired British spy played by Charlize Theron in Atomic Blonde. Dialogue like this puts a fine point on Lorraine’s status as a femme fatale, overemphasizing what the viewer already knows: she’s the deadliest agent in the midst of the film’s cloak-and-dagger scenario. The screenplay, based on Antony Johnston’s moody graphic novel The Coldest City from 2012, has been adapted by Kurt Johnstad (300) into an unsubtle, unemotional tale of espionage and virtuoso action scenes. Theron once again proves herself an imposing lead as a tough, unrelenting heroine (recalling Furiosa in Mad Max: Fury Road), and director David Leitch places her in some impressive hand-to-hand combat sequences. Some have compared Atomic Blonde to John Wick (2014), which Leitch co-directed; but this film lacks the emotional stakes that drove Keanu Reeves’ character in that film, and the resulting style-over-substance approach here feels hollow.

Set in 1989 around the fall of the Berlin Wall, the convoluted and labyrinthine plot involves one quite similar to that of Mission: Impossible (1996): both films entail spies trying to either obtain or prevent the release of The List, which contains the names of secret agents and their real-life identities. Lorraine has been assigned to recover the film’s MacGuffin from a defector codenamed Spyglass (Eddie Marsan), while she must also learn the identity of a mysterious double-agent, known only as Satchel. A depraved MI6 agent named David Percival (James McAvoy) is Lorraine’s rendezvous to secure Spyglass and The List. Of course, nothing goes as planned, Lorraine’s cover is blown, and she’s pursued by a variety of Russian goons. Amid the double-crosses and shootouts that ensue, Lorraine beds French intelligence agent Delphine (Sofia Boutella) in a sex scene that feels emotionally cold and gratuitous.

The story is told mostly in flashback through the framing device of Lorraine’s report to her MI6 superior (Toby Jones), as well as an unwelcomed CIA chief (John Goodman). And while you might suspect that either Jones’ or Goodman’s characters have some greater relevance to the twisting plot, you would be wrong. There’s almost no point to the film’s structure. Meanwhile, Theron’s character consists of several repeated attributes but no genuine personality, aside from being a steely, badass pansexual. When we first meet her, she emerges from a bath of ice, bruised and battered. We might assume the ice bath was due to her wounds, but she takes another ice bath later, despite being in fine condition. She never eats; her diet consists of cigarettes and Stoli vodka on the rocks. As for personal motivations or emotional context, there are none. Over the nearly two-hour runtime, the film gives us no reason to care about the proceedings. What’s more, she feels overshadowed by cinematographer Jonathan Sela’s color-saturated lensing and neon-lit interiors, which ooze with the period’s conflicting states of political turmoil and cultural outpouring.

Indeed, Atomic Blonde opens to New Order’s “Blue Monday,” and the film continues to drop song after memorable song, the soundtrack comprised of mostly post-punk and New Wave hits popular in Berlin at the time. Each tune—such as David Bowie’s “Cat People,” Duran Duran’s “Hungry Like the Wolf,” Falco’s “Der Kommiser,” and enough others to build a Time Life best-of-the-‘80s album—proves so distinct that watching the film becomes an almost music video exercise. In fact, MTV features prominently in the backdrop, with a brief appearance by Kurt Loder asking, “Is it art or is it just plagiarism?” That’s a perfect question for Atomic Blonde, which seems to borrow most of its plotting and mise-en-scène from other sources. Homage and references do not automatically disqualify a film as art; they do, however, bring into question the quality of the art’s ability to integrate exterior sources. Leitch’s film seems more interested in other material than making his own film a cohesive, emotionally engaging story. Take a chase sequence that enters a Berlin moviehouse screening Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), a film about the importance of art, at least in part. Leitch’s use of the Russian filmmaker’s elusive, metaphysical work of film art seems more substantive than it really is, suggesting Atomic Blonde isn’t as smart or imaginative as it wants to be.

The questions of the film’s dull theme about artistic merit aside, Leitch’s treatment is at times breathlessly exciting. A long, brutal fight sequence on a staircase follows Lorraine down several flights, into an apartment, and outside into the street. It may be the single most impressive fight put to film in years, and what is more, Leitch was so confident in the sequence that he removed all music from it entirely, allowing the sound of fist-to-body impacts, gunshots, and Theron’s battle cries to dominate the scene. If only he had trusted the rest of his film as much, the audience may not have suffered the onslaught of distractingly great music that, instead of supporting their scenes, steals them. Likewise, the talented cast and formal technique feel trampled by the overstylized and undermotivated narrative. While capably made by Leitch and commanded by Theron, Atomic Blonde contains an imbalance of style and story that ultimately leaves the film an empty experience.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review