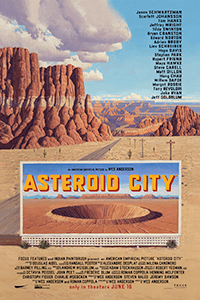

Asteroid City

By Brian Eggert |

Note: After debuting at the Cannes Film Festival last month, Asteroid City will be previewed at a special Alamo Drafthouse screening on June 12 before its wide release on June 23, 2023.

Wes Anderson has become a jewelry maker, fashioning pretty objects with creative facets, decorations, and polish that invite distanced appreciation. Like pieces of jewelry, Anderson’s latest films contain little innate emotion, only the suggestion of it. They are fine works of art, to be sure, but like a ring to its recipient, they seem to rely more on the sentimental value that the spectator brings than an inherent emotional draw. This quality of Anderson’s work has only become more heightened in recent years. His peculiarities, aesthetic fastidiousness, and capacity for moving material may have reached their height nearly a decade ago with, arguably, his best work, The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). That film matched its considerable style with emotional weight and a theme that argues in favor of art for art’s sake. But Anderson has struggled to find anything new to say in his recent stylistic exercises, Isle of Dogs (2018), The French Dispatch (2021), and his latest, Asteroid City. The film is an articulately cut, arranged, and designed piece of cold metal and precious stones that one looks upon with admiration. Whether one wants to wear it on their finger remains the question.

My own response to Wes Anderson films in the last 25 years has gone from unchecked admiration and personal resonance to a decided lack of interest. For example, it was an eye-opening shock that I did not love Isle of Dogs. This soon led to feeling entirely removed from the experience of watching The French Dispatch. So it’s not surprising that my response to Asteroid City is one of chilly appreciation, the way one admires but does not fall in love with the effort that goes into a finely tuned machine. I respect Anderson’s recent efforts and cannot fault the technical filmmaking, but like one of the recent AI-generated parodies of Anderson’s work, the film has a self-reflexivity and self-conscious style that produce a distancing irony, which is detrimental to any significant pleasure. Then again, perhaps Anderson is earnest and not meta at all. Perhaps his style is so singularly unchanging that it cannot help but feel like a self-reference, given his heightened meticulousness over the years, and how his recent work fails to evoke the same reaction as his earlier output, such as Rushmore (1998) and The Royal Tenenbaums (2001).

Like most Anderson features, the punctilious design and structure remain central to Asteroid City. The film opens with a black-and-white TV segment reminiscent of early 1950s broadcasting, complete with a 4:3 aspect ratio. Bryan Cranston appears as an announcer, delivering an Edward R. Murrow-style presentation. Our host explains the origins of the titular play, written by Conrad Earp (Edward Norton), which is then acted out at the television studio along with a performance of this “modern theatrical production.” The film proper, captured in a 1.85:1 aspect ratio, takes place in a desert town, home to the Arid Plain Meteorite landing site and situated near atomic testing. The framing devices in the film go beyond the play-on-TV conceit. They also include chapter headers, monochrome sequences set behind the scenes of the staged play, and various interruptions by Cranston’s character, sometimes breaking the logic of these established devices with a comic touch of postmodernism. At one point, Cranston enters a scene, and everyone else stops to shoot him an accusatory glance. “Am I not in this?” he asks before shuffling out of frame. Moreover, every actor in this unbelievably star-studded ensemble plays not only their character in the filmed play but also the actor playing that character, giving everyone a chance at double duties.

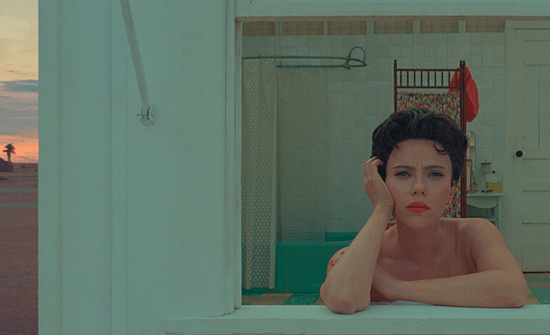

Most of Asteroid City involves characters in an empty town in the American Southwest. At the resident motor court, Steve Carrell plays a hotel manager who’s always ready with an “I understand” and a wall of increasingly peculiar vending machine commodities (snacks, martinis, real estate, etc.). The local mechanic (Matt Dillon) might fix your car or render it undrivable. A scientist (Tilda Swinton) searches for signs of alien life. The small town hosts a Junior Stargazers competition, so Asteroid City has a cross-section of visitors. Central to the story is war photographer Augie Steenbeck (Jason Schwartzman), a widower who finally tells his four children, the gawky teen Woodrow (Jake Ryan, from 2018’s Eighth Grade) and his three young daughters who identify as monsters, that their mother has died. Their grandfather (Tom Hanks) meets them in the town after their car breaks down. Meanwhile, Augie forms a friendship and eventual affair with actress Midge Campbell (Scarlett Johansson), whose bungalow sits across from his. Other Anderson newcomers and mainstays appear, including Hope Davis, Rupert Friend, Maya Hawke, Hong Chau, Willem Dafoe, Steve Park, Tony Revolori, and Jeff Goldblum.

Most of Asteroid City involves characters in an empty town in the American Southwest. At the resident motor court, Steve Carrell plays a hotel manager who’s always ready with an “I understand” and a wall of increasingly peculiar vending machine commodities (snacks, martinis, real estate, etc.). The local mechanic (Matt Dillon) might fix your car or render it undrivable. A scientist (Tilda Swinton) searches for signs of alien life. The small town hosts a Junior Stargazers competition, so Asteroid City has a cross-section of visitors. Central to the story is war photographer Augie Steenbeck (Jason Schwartzman), a widower who finally tells his four children, the gawky teen Woodrow (Jake Ryan, from 2018’s Eighth Grade) and his three young daughters who identify as monsters, that their mother has died. Their grandfather (Tom Hanks) meets them in the town after their car breaks down. Meanwhile, Augie forms a friendship and eventual affair with actress Midge Campbell (Scarlett Johansson), whose bungalow sits across from his. Other Anderson newcomers and mainstays appear, including Hope Davis, Rupert Friend, Maya Hawke, Hong Chau, Willem Dafoe, Steve Park, Tony Revolori, and Jeff Goldblum.

To call the film crammed would be an understatement. On the periphery, a dozen characters fill every moment of screentime with playful gags and tender asides. A Junior Stargazer nominee (Aristou Meehan) constantly asks others to dare him to perform stupid feats. The subplot offers amusing background moments until the boy’s hard-nosed father, J.J. Kellogg (Liev Schreiber), finally confronts his son about his obsession with dares, and the response is devastating. Elsewhere, a wrinkle involving a UFO landing, an Alien spotting, and a government quarantine forces everyone to remain in town and interact, drawing out their stories. Much about Augie’s storyline resonates, though his scenes involve a familiar sadness and widower situation, recalling Ben Stiller’s character in The Royal Tenenbaums. But just when you connect to a character, Anderson reminds us that the scenes in Asteroid City are artifice. The backdrop looks constructed from sculpted foam and matte paintings, and the sets look intentionally contrived. It’s as though Anderson has made a movie from one of Max Fischer’s plays in Rushmore, and he’s using his characters’ basic dramatic situations to provide a thesis on aesthetic theory.

Like all of Anderson’s efforts since The Grand Budapest Hotel, Asteroid City is a compendium of aesthetic traits associated with the filmmaker: The precise, angular camera movements by cinematographer Robert Yeoman capture the story in tableau shots, evoking a vivid diorama. The airy and nimble score by Alexandre Desplat keeps the tone lighthearted, even in melancholy scenes. The narrative structure seems almost mathematical, best described in typical Anderson buzzwords: heartwarming, whimsical, offbeat, quirky, and idiosyncratic. But Anderson has not pushed himself, leading to lines of dialogue and situations that feel like caricatures of his auteurist voice. For instance, the burgeoning romance between Woodrow and Midge’s daughter Dinah (Grace Edwards) feels drawn out of Moonrise Kingdom (2012). And the dialogue feels like someone writing a mock Anderson script. When one character suggests that the stop-motion animated Alien looked at them like they were doomed, someone replies, “Maybe we are.” With lines like this and characters who seem replicated from templates in Anderson’s earlier films, Asteroid City feels like the writer-director making banal observations about his artistic output.

The play, according to Earp, is about “infinity”—which is perhaps a way of remarking on how life and art imitate each other, while art makes allusions to other art. Yet, between Earp and the play’s director, Schubert Green (Adrien Brody), they seem to be locked in a mode of creative experimentation designed not to achieve a particular message, not to explore humanity, but to push their medium’s limits. However, the test of any artist is how they apply their toolkit and talent to find new meaning, and Asteroid City suggests that Anderson has stopped wanting to grow, apart from becoming ever more intricate. With his distinct, authorial preoccupations remaining as regular as the tides, and his work now subject to satire, the work itself has started to feel boxed in—similar to how his movie has been contained within a series of self-reflective framing devices, his characters have been trapped in roles they do not understand, and everyone is trying to understand the vastness of the universe. Sure enough, it’s a lofty topic. But in the hours after watching this finely articulated trinket, I realized that its profundity is fleeting and its emotional consequence is minor. If Asteroid City is a gaudy piece of ornamented jewelry, festooned with gemstones and engravings, I yearn for Anderson’s first decade or more of work, with the comparative simplicity and meaning of an unadorned wedding band.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review