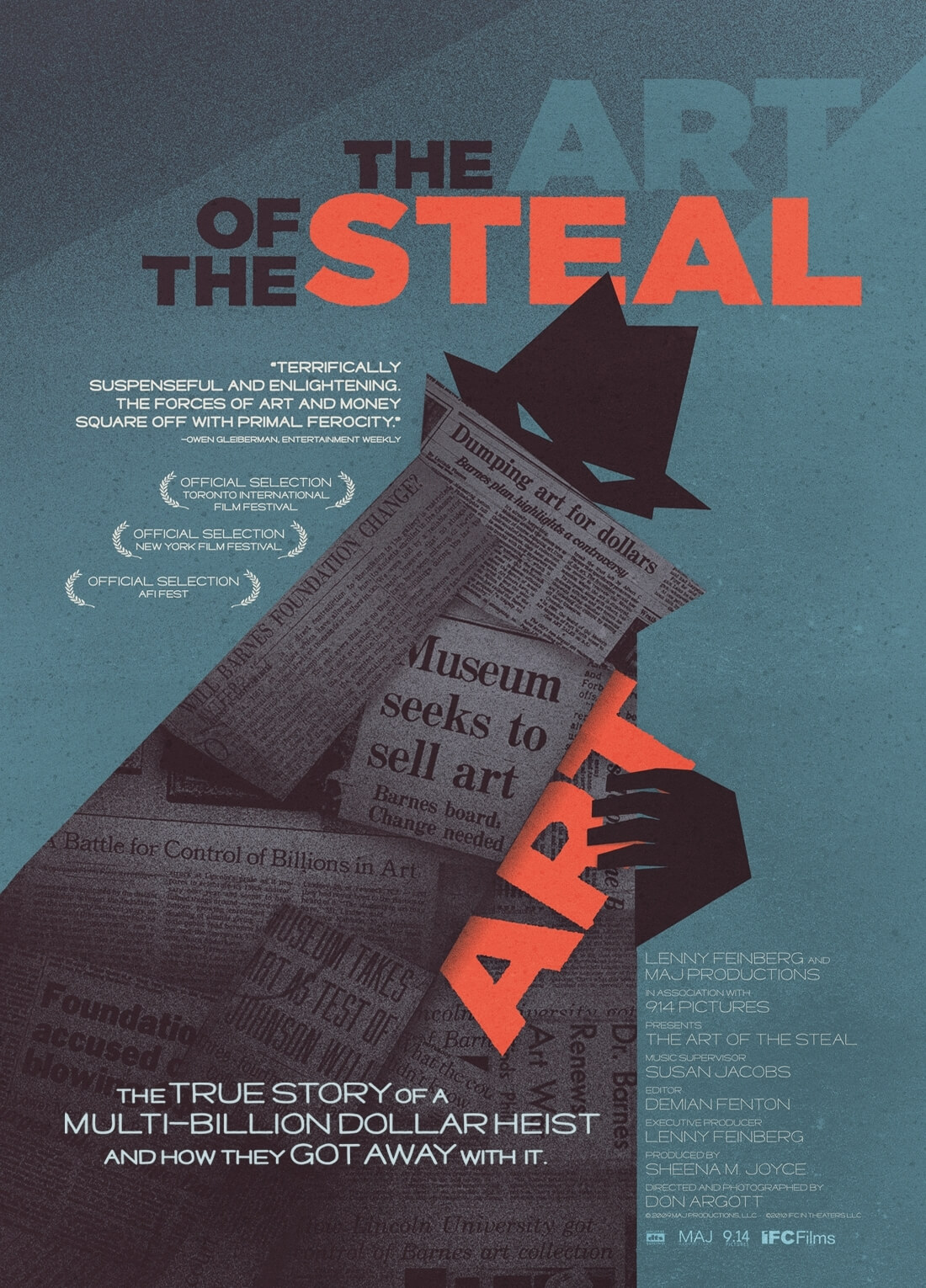

Art of the Steal

By Brian Eggert |

In the art community, there’s a burgeoning problem of powerful people using their influence to requisition significant pieces of history, if only to illustrate their own importance. In the last hundred years, the preservation of art has become a big business, one that signifies the status of those supporting it, much like an expensive wardrobe or flashy car does. The Art of the Steal is an incredibly involving documentary about elitists and power brokers who ignore a legal will, break laws, lie, and manipulate the system to exorcize their desperate need to appear culturally adept. The story is a very specific one, but it’s telling of a number of such cultural robberies going on throughout the planet right now.

Directed by Don Argott, this smoking gun doc brings to light all the sordid details of the greatest art scandal since Hitler stole Europe’s art treasures in WWII (as detailed in another art doc, The Rape of Europa). The thieves are Philadelphia lawyers, businessmen, politicians, and would-be art lovers, all scheming to pilfer priceless works from the greatest single private collection of Post-Impressionist modern art, The Barnes Foundation. The doc plays like an investigatory thriller, slowly unfurling the facts as they become more and more scandalous, more absurd, more enraging, and frustrating. It’s a realist’s David and Goliath tale, wherein the gargantuan Goliath proves victorious and the beaten David has nothing to do except make a winning documentary about his defeat.

The Barnes Foundation was established in 1922 by Dr. Albert C. Barnes, a private art collector who made his fortune in pharmaceuticals. He began purchasing modern art before it was considered stylish before art enthusiasts saw the appeal of the non-classicized representations of the Post-Impressionists. Barnes began to buy the works of Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Vincent Van Gogh, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and others because he had evident taste. But he did not buy paintings by these masters simply because they were ‘a Matisse’ or ‘a Cézanne’, or because they were expensive. He avoided buying the artists’ lesser works. He bought with an appreciation for craft and history and composition and technique. Over time, no single museum would have the volume of these masters as Barnes.

When he built The Barnes Foundation in the suburbs of Philadelphia to house his collection, Barnes presented art as a visual relationship between human beings, as opposed to the stale, white-walled, hygienic museum experience. In the Barnes Foundation, a single work of art speaks to another through Barnes’ own visual presentation, so that French and Italian, and African works might all be in the same room. And yet the themes and visual styles of each, despite the varying nationalities, all appear similar, proving that art is life and life is the same the world over. It’s impossible to walk through Barnes’ establishment in an hour, and the type of casual museumgoer who could stream through an exhibition in under an hour wasn’t allowed in Barnes’ building. Public showings were limited, and visitations played out more like mobile classrooms that appreciated the depth and impact of art. Matisse himself said The Barnes Foundation was the only “sane” place to see art in America.

At the only public exhibition of this artwork in downtown Philadelphia, the critics called the collection “primitive” and “debased art”. Barnes then opted to keep his collection in the private sector, making his works available only to those with a purist interest in the art. He wanted to educate, not profit; he wanted to avoid becoming a faux cultural center like the majority of today’s McMuseums. The elitist art snobs were not allowed to see his works, only students and teachers, and as always the common man. When the “experts” eventually began to see the value of modern art, suddenly the Barnes collection was not so primitive. Museums now saw Cézanne, Matisse, and Van Gogh as crucial modern masters. All at once the Barnes Collection went from a “debased” assemblage of paintings to a collection worth an estimated $30 billion, although this sort of estimation is relative because the works have an immeasurable cultural value.

The documentary follows in precise detail the chain of events that eventually led key players in Philadelphia’s political realm to arrange the virtual theft of the Barnes Collection to a new museum downtown, despite Barnes’ final legal wish for his collection to remain out of their hands. Barnes wrote in his will that his collection should not be loaned nor exploited commercially and that the Barnes would be open to the public two days a week. In 1951, Barnes died and left his collection to colleague Violetta Di Mazia, who died in 1988. After the remaining trustees died, according to Barnes’ will the Foundation was left to Lincoln University. This struggling college quickly took immediate funds to repair their school in exchange for outsiders buying interest in the board of The Barnes Foundation.

From there a dizzying circle of politicians dig their fingers in the dirt, most of them associated with Barnes’ past enemies, all making their way to an illegal move of the art. The players include Lincoln University rep Richard H. Glanton, state governor Edward G. Rendell, and publisher Walter Annenberg—all operating according to a plan that was the brainchild of Ray Perelman, a tasteless elitist with the power and money to move politicians and judges in whatever direction he chooses. Their plan was to claim The Barnes Foundation would never work economically in its present location, so they brought the Foundation “out of the Dark Ages”, but only, they claim, because the actual building was beginning to deteriorate and they had no choice. What the documentary exposes is proof that these moneyed folk never intended to try a restoration of the Foundation’s building. It’s all summed up rather nicely when Philadelphia’s Mayor Street brags that the profits from a year at the new Barnes Gallery in downtown Philadelphia will equal that of three Superbowls.

Forget about the art for a moment. At the root of the problem is the matter of honoring one’s will. If wills are so easily overlooked, then why do we have them? Consider your possessions and how you want them distributed upon your death. Now consider how you and those who love you would feel if those items were slyly appropriated for a “greater cause” despite it going against your will. If there’s one thing this documentary shows us, it’s that your will means nothing when there’s money and power vying to get their hands on what was yours. Barnes had no kin to look over his estate, and those placed in charge of the Foundation did not honor his final wishes, largely because money was dangled before their faces. What remains is a sad example of political corruption, of the art world being transformed into an industry, and the ongoing trend of governments appropriating art because they have the influence to “prove” it’s theirs.

Albeit the presentation of a one-sided argument, The Art of the Steal is nonetheless a captivating tale about the flexibility of the law when money is involved. Granted, the thieves in this story maintain that more people will get to see the Barnes Collection when it moves into its new downtown location in 2012, but that’s not the point. The point is that they’re going against a legal will, they lied to the courts to make this move, and they never tried to make The Barnes Foundation work. It was always their intent to move this art and profit from it. And once you start treating art like a commodity no more unique than one nugget of gold from another, it loses its meaning. Barnes didn’t want everyone to see his collection, and since the art was his, he had the right to make that distinction. Sadly, the documentary offers little the general public can do to prevent the impending move, other than lament the decision through protest. Still, the well-told story in documentary form does wonders to get the blood boiling and get audiences thinking seriously about how art should be viewed.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review