Armageddon Time

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review was originally published for the 2022 Twin Cities Film Fest.

From the foreboding title on through the autumnal colors of Darius Khondji’s gorgeous cinematography, the complex reach of the narrative, and the way every actor completely inhabits their character on the cusp of a monumental change, Armageddon Time is another of writer-director James Gray’s deceptively simple films. Although its title hints at a save-the-world blockbuster or post-apocalyptic survival story, Gray borrows from a song on The Clash’s 1979 album London Calling called “Armagideon Time,” a cover of Jamaican reggae musician Willie Williams’ original. The song, performed in its originally rebellious and underground style, would have been newish in the film’s setting of Queens, New York, in 1980. Its lyrics observe that “A lot of people won’t get no supper tonight/A lot of people won’t get no justice tonight.” Gray’s intricate and nuanced storytelling reflects upon his childhood awakening to these lyrics and their meaning through a beautiful work of autofiction. But unlike many Hollywood dramatists as of late, Gray resists turning his story into a polemical discussion of modern-day America, even though he explores ideas that will continue to characterize and haunt the next several decades of American life.

Gray belongs on a shortlist of American filmmakers willing and capable of weaving a commentary on the present into his work in a sophisticated way, which doesn’t betray the integrity of his narrative. Although he regularly transitions between genres—science fiction in Ad Astra (2019), historical epic in The Lost City of Z (2017), period drama in The Immigrant (2013), family crime saga in We Own the Night (2007)—each example is invariably more than its category or logline implies. Watching a Gray film is like opening the page on substantive work of literature, knowing only about the cover photo and brief description on the dust jacket, and only upon reading it, realizing that the author has brought an entire world to life, rich with complicated characters and narrative turns that resonate beyond face value. Perhaps that’s why his films never perform well at the box office, despite his ability to nab bankable stars to headline his projects. Gray doesn’t deliver an easily packaged and sold Hollywood product ready for mass consumption; he’s one of the most consistently novelistic filmmakers working today.

Armageddon Time is Gray’s most personal film, told with a profound sense of character, place, and the perspective of an inward and artistic boy. The setting draws from his childhood in Queens, growing up as a descendant of Jewish immigrants who fled the pogroms and racism of Eastern Europe, and ultimately, realizing what that means to his identity. His onscreen counterpart, Paul, played by Banks Repeta, has the same reddish mop of curly hair and the same devotion to his art as Gray—Paul likes to draw and dreams of becoming a famous painter. Despite rooting his film in the past, Gray doesn’t look back with rose-colored glasses or an overly nostalgic romanticism, save for the general sense of discovery and innocence that comes with childhood. Instead, he eschews the usual idealization of so-called simpler times and recognizes that times have always been confusing and troubled. But in our youth, we aren’t yet attuned to the patterns and presence of history, prejudice, and trauma that exists all around us. Yet, once we see what’s projecting the shadow on the cave wall, there’s no going back to believing the illusion.

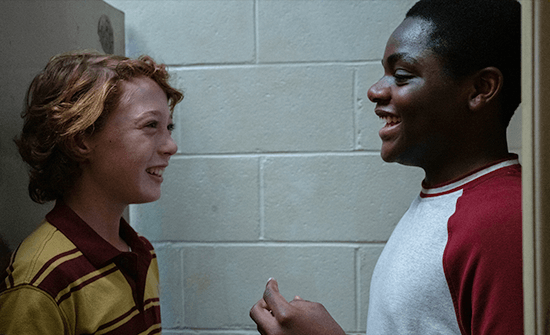

Paul starts his sixth-grade year in public school under the abrasive teacher Mr. Turkeltaub (Andrew Polk), whom the children call “Turkey.” The teacher doesn’t look kindly on Paul’s knack for drawing or making his peers laugh, and worse, he singles out Paul’s friend, Johnny (Jaylin Webb), the only Black student in class. Johnny has been held back a year, probably because Turkey has blatantly targeted him, issuing punishments that range from cleaning the chalkboard to making him sit silently at a desk at the front of class, unable to participate in the lesson. When Johnny talks back in defiance of his treatment, Turkey loses his temper and calls him an “animal” under his breath, and the teacher’s clear belief that Johnny doesn’t belong in the class goes unchallenged. Paul begins to recognize how and why Turkey treats Johnny differently when Paul makes the class laugh at one point, but Turkey reflexively blames Johnny. Even so, Paul doesn’t correct him or stand up for his friend, perhaps out of fear—though, he later apologizes to Johnny, saying he would have said something had there been any real trouble. Over the course of Armageddon Time, Paul learns how formative such moments can be, and how his inability to act will continue to nag at him.

Paul starts his sixth-grade year in public school under the abrasive teacher Mr. Turkeltaub (Andrew Polk), whom the children call “Turkey.” The teacher doesn’t look kindly on Paul’s knack for drawing or making his peers laugh, and worse, he singles out Paul’s friend, Johnny (Jaylin Webb), the only Black student in class. Johnny has been held back a year, probably because Turkey has blatantly targeted him, issuing punishments that range from cleaning the chalkboard to making him sit silently at a desk at the front of class, unable to participate in the lesson. When Johnny talks back in defiance of his treatment, Turkey loses his temper and calls him an “animal” under his breath, and the teacher’s clear belief that Johnny doesn’t belong in the class goes unchallenged. Paul begins to recognize how and why Turkey treats Johnny differently when Paul makes the class laugh at one point, but Turkey reflexively blames Johnny. Even so, Paul doesn’t correct him or stand up for his friend, perhaps out of fear—though, he later apologizes to Johnny, saying he would have said something had there been any real trouble. Over the course of Armageddon Time, Paul learns how formative such moments can be, and how his inability to act will continue to nag at him.

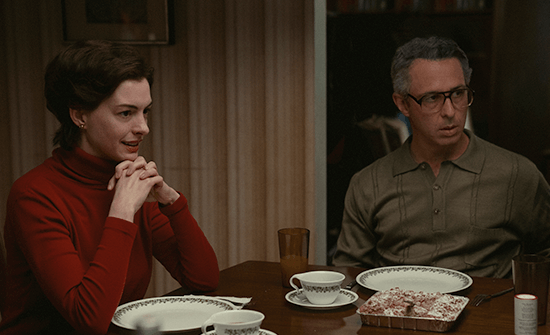

Somewhat aware of his relative privilege compared to Johnny, Paul describes his family as “rich” and brags about how his mother runs the school from her position on the PTA board. But the Graff family isn’t bringing in millions, and his mother, Esther (Anne Hathaway), doesn’t quite have the authority over the school that Paul believes. In reality, the boy’s father, Irving (Jeremy Strong), works as a blue-collar plumber, ever tightly wound and capable of real rage. His mother isn’t some eternally patient and nurturing figurehead; rather, she frets over the grocery bill and has moments of impatience. Paul’s bullying older brother Ted (Ryan Sell) is too much older to be a friend, leaving Paul’s closest familial bond with his grandfather, Aaron (Anthony Hopkins), a wise jokester who gives Paul a toy rocket in an early scene. They plan to launch it in Flushing Meadows, as soon as Paul puts it together. In the meantime, Gray establishes the Graff family dynamic with lived-in scenes at the dinner table, where Irving prattles on about his favorite bridge style, and the grandparents urge Esther and Irving to send Paul to private school like his older brother.

Gray never sentimentalizes these family scenes, even though they often feel warm and familiar. But then the dinner table conversation veers into stark territory when Paul’s father and other grandparents make casually racist remarks about who’s moving into the neighborhood. Aaron seems to actively counteract these moments by telling Paul about his grandmother, Mickey (Tovah Feldshuh), a Ukrainian Jew persecuted by the Cossacks. She escaped through Poland and then England, where they met, and later came to America through Ellis Island. Gradually, Paul begins to recognize his privilege in relation to Johnny and that he, too, could become a target because of his background. But Paul sees Johnny as a genuine friend, going so far as to steal money from his parents for Johnny so they can attend a school trip to the Guggenheim Museum together. After becoming entranced by a Kandinsky painting, the two ditch the field trip and escape to Central Park, then an arcade and a record shop to buy a Sugar Hill Gang album—unleashed scenes that recall the energy of François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959) in their freedom from school and authority.

There’s also a dreamlike sense of fantasy to Armageddon Time, where Paul loses himself in his imagination. Inside the Guggenheim, Paul imagines his glory and acceptance as a fine artist, complete with Turkey acknowledging his genius for creating the best superhero drawing ever. These whimsical asides feel inspired by Federico Fellini’s 8 ½ (1983) or perhaps even Bob Clark’s A Christmas Story (1983), where Paul’s mental images take over the screen. Gray and editor Scott Morris weave in scenes from television and projections of Paul’s daydreams that break the film’s otherwise immersive and convincing period mise-en-scène. Elsewhere, Gray’s ability to get inside Paul’s head captures that familiar childhood moment after Mom says goodnight, and you’re alone in the dark, but you can half-hear voices outside of your bedroom door and others from the day inside your head—images that echoed my own memories of falling asleep as a kid. And similarly, there’s the sensation of Dad singing a silly wake-up song, only I remembered my dad’s rendition of “Good Morning” from Singin’ in the Rain (1952). In Gray’s hands, these are not so much “remember when” moments as textured scenes that bring the Graff family to life in a manner that evokes our own experiences.

There’s also a dreamlike sense of fantasy to Armageddon Time, where Paul loses himself in his imagination. Inside the Guggenheim, Paul imagines his glory and acceptance as a fine artist, complete with Turkey acknowledging his genius for creating the best superhero drawing ever. These whimsical asides feel inspired by Federico Fellini’s 8 ½ (1983) or perhaps even Bob Clark’s A Christmas Story (1983), where Paul’s mental images take over the screen. Gray and editor Scott Morris weave in scenes from television and projections of Paul’s daydreams that break the film’s otherwise immersive and convincing period mise-en-scène. Elsewhere, Gray’s ability to get inside Paul’s head captures that familiar childhood moment after Mom says goodnight, and you’re alone in the dark, but you can half-hear voices outside of your bedroom door and others from the day inside your head—images that echoed my own memories of falling asleep as a kid. And similarly, there’s the sensation of Dad singing a silly wake-up song, only I remembered my dad’s rendition of “Good Morning” from Singin’ in the Rain (1952). In Gray’s hands, these are not so much “remember when” moments as textured scenes that bring the Graff family to life in a manner that evokes our own experiences.

Things change when Paul gets caught smoking pot with Johnny at school. For one, Gray shows a bracing scene of Irving punishing Paul, who hides in the bathroom to avoid his father’s punishment—and Strong is incredibly unhinged in this difficult-to-watch moment. The incident convinces Paul’s parents to put him into the same Forest Hills private school as Ted. Meanwhile, Johnny drops out of school, unwilling to face Turkey’s abuse any longer, and evades social services after his guardian-grandmother’s dementia progresses. In this new chapter of Paul’s education, he meets racist private school students who use the n-word without hesitation. He also meets the school’s benefactor on his first day: Fred Trump (John Diehl), his face like fried chicken skin, who grills Paul about the ethnicity of his last name (“What kind of name is that?”). Then, Maryanne Trump (Jessica Chastain, in a single-scene cameo) gives an ironic speech about the value of hard work and not relying on handouts, despite her own family’s entrenched nepotism.

In these brief scenes, Gray acknowledges the kind of values that will be rewarded in the coming decade in America, as well as the unwritten yet institutionalized racism that continues. And even though Paul’s family can be similarly close-minded at times, they at least recognize the grim warning signs of Reagan’s presidency. Still, Paul’s parents want him to think about practicalities and his financial future—signifiers of success in the ‘80s—as opposed to following his passion. Their concern is about having enough money to pay bills and raise their children, because those priorities have been instilled in them from the previous generation. Only Grandpa Aaron recognizes that Paul can do more, gifting him a set of oil paints so that he may explore his talent. Grandpa Aaron knows the consequences of falling in line and allowing others to dictate your journey—behavior that reinforces outmoded traditions and troublesome institutions. So the lingering question is: Will Paul fall in line with his parents and the country’s money-minded trajectory, or will he follow his grandpa’s lesson?

Somewhere between their school-ditching escapades and Johnny’s need to hide out in Paul’s backyard clubhouse, Paul begins to process the unfairness of his world. So he plans to run away with Johnny to Florida, where he can work as an artist for EPCOT and Johnny as an astronaut for NASA, but their plan falls through. In the aftermath, Paul receives a crushing lesson about privilege and social inequality from his father’s interaction with the police. It’s a shattering moment. And it’s reinforced by the late, tender scene in Flushing Meadows between Paul and Grandpa Aaron—the film’s most emotionally raw moment. Esther remains in the car, watching teary-eyed because she knows her father is dying, while Paul is oblivious to the scene’s gravity. Hopkins, who somehow disappears into this role, regardless of being a screen icon, gives a raw performance when Grandpa Aaron tells Paul to stand up to bigots. “You gotta do something, you gotta say something.” And finally, to those people and institutions who would discriminate: “Fuck ‘em”—a sentiment echoed later when the camera pulls away, following Paul out of the problematic institution to choose his own path. Although Armageddon Time is a gently paced film that nonetheless captures the speed at which childhood unfolds into adolescence, there’s a potent streak of defiance at this moment, accented by the titular antiestablishment song on the soundtrack.

Somewhere between their school-ditching escapades and Johnny’s need to hide out in Paul’s backyard clubhouse, Paul begins to process the unfairness of his world. So he plans to run away with Johnny to Florida, where he can work as an artist for EPCOT and Johnny as an astronaut for NASA, but their plan falls through. In the aftermath, Paul receives a crushing lesson about privilege and social inequality from his father’s interaction with the police. It’s a shattering moment. And it’s reinforced by the late, tender scene in Flushing Meadows between Paul and Grandpa Aaron—the film’s most emotionally raw moment. Esther remains in the car, watching teary-eyed because she knows her father is dying, while Paul is oblivious to the scene’s gravity. Hopkins, who somehow disappears into this role, regardless of being a screen icon, gives a raw performance when Grandpa Aaron tells Paul to stand up to bigots. “You gotta do something, you gotta say something.” And finally, to those people and institutions who would discriminate: “Fuck ‘em”—a sentiment echoed later when the camera pulls away, following Paul out of the problematic institution to choose his own path. Although Armageddon Time is a gently paced film that nonetheless captures the speed at which childhood unfolds into adolescence, there’s a potent streak of defiance at this moment, accented by the titular antiestablishment song on the soundtrack.

Gray has made a seemingly straightforward coming-of-age drama where the innocence of youth gives way to an awareness of institutions with which Paul, and therefore Gray, remains at odds. To be sure, the political stakes of Armageddon Time prove almost as severe as the personal. But the final shots suggest that Paul’s defiance against institutions that would label him “slow” for his wandering imagination or disallow someone like Johnny only inspire him to live up to his grandfather’s words—“Don’t be nervous. Be bold.”—and create his art. With this touch, Gray’s particular brand of dramaturgy becomes naturalistic but also resoundingly symbolic in an expressive, almost theatrical way—a characteristic of the writer-director’s films that lends them their novelistic quality. While marvelously acted by the cast (particularly Repeta, Webb, and Hopkins) and full of achingly relatable scenes from Gray’s childhood, the film acknowledges how those simpler times were symptomatic of the problems that continued to spiral and horrifically climaxed in recent years. Armageddon Time resists pure nostalgia; rather, Gray remembers cherished moments of his youth while also weighing how the past blared warning signals of things to come. And, in its final moments, Paul’s lesson becomes Gray’s rebellious, even revolutionary statement against the establishment.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review