Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.

By Brian Eggert |

Judy Blume’s Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. is one of those essential books that every young person should read. After its publication in 1970, millions of children identified with Blume’s frank account of a sixth-grade girl facing adolescence—the changes, anxiety, and uncertainty. Besides those universal concerns, the book was controversial for its portrait of girlhood, including an honest depiction of menstruation, training bras, secret clubs, and first kisses. All that might be enough, except Blume also stitches the narrative together with her protagonist’s questions about faith. While girls learned or recognized themselves in Margaret, boy readers like myself learned how to empathize with what our classmates were experiencing. But for all of her candor, Blume’s coming-of-age story meant as a sincere book for grade-school kids wound up on censored lists in schools around the United States, particularly after the emergence of Reagan-era conservatism. Overprotective parents raised their concerns forty years ago, afraid youngsters might learn about and prepare for what awaits them, and in the new post-Trump extremism, they’re doing it again.

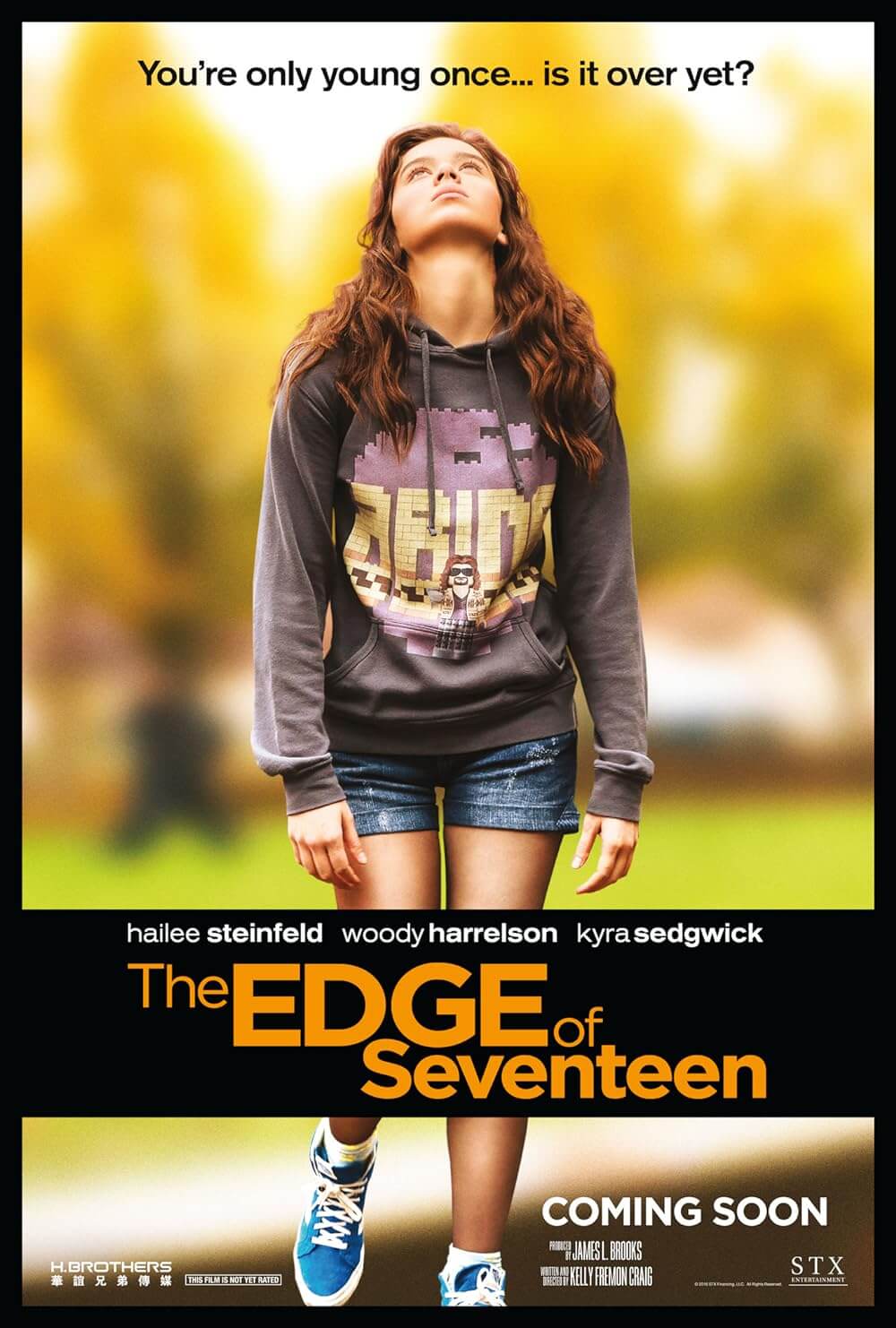

So it’s ideal timing that a screen adaptation of the bestseller has finally arrived after more than a half-century, if only to give young people better access to a story that can ease their precarious journey into teendom. The film was written and directed by Kelly Fremon Craig, who already made one of the essential teen comedies, the earnest and hilarious The Edge of Seventeen (2016)—which, in retrospect, it bears many similarities to Blume’s brand of fiction. James L. Brooks produced Craig’s debut and Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. with his production company, Gracie Films, which hasn’t made a lot of films, but it has made some great ones: Broadcast News (1987), Big (1988), and Jerry Maguire (1996). Add Craig’s latest to the list. Her version of Blume’s book might be a perfect movie for realizing what it sets out to achieve. Unlike so much teenage fare, it never talks down to its audience, young or old; it never resorts to schmaltz or an unearned emotional payoff; it never takes the easy way out.

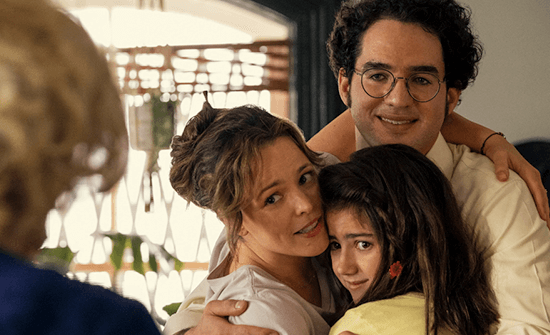

The story opens in 1970 with Margaret Simon, earnestly played by newcomer Abby Ryder Fortson, returning home from summer camp to find herself confronted by a period of transition. Her father, Herb (Benny Safdie), has taken a promotion, prompting a move that will relocate the family to the New Jersey suburbs. Not only will Margaret have to make new friends, but she will no longer see her Grandma Sylvia (Kathy Bates) on the regular. But her mother, Barbara (Rachel McAdams), promises they’ll have more time together now. The upheaval is softened after Margaret makes a new friend, Nancy (Elle Graham), a future mean girl who welcomes the newbie into her friend group, which includes Gretchen (Katherine Mallen Kupferer) and Janie (Amari Alexis Price). Nancy and the others introduce Margaret to a whole series of new anxieties. For instance, one price of entry into the group requires Margaret to acquire her first bra, and together they perform an iconic exercise from Blume’s book, chanting: “We must, we must, we must increase our bust!” But even as they anticipate the change in their bodies, Nancy mocks Laura (Isol Young), a quiet early bloomer in their class, for maturing early.

The story opens in 1970 with Margaret Simon, earnestly played by newcomer Abby Ryder Fortson, returning home from summer camp to find herself confronted by a period of transition. Her father, Herb (Benny Safdie), has taken a promotion, prompting a move that will relocate the family to the New Jersey suburbs. Not only will Margaret have to make new friends, but she will no longer see her Grandma Sylvia (Kathy Bates) on the regular. But her mother, Barbara (Rachel McAdams), promises they’ll have more time together now. The upheaval is softened after Margaret makes a new friend, Nancy (Elle Graham), a future mean girl who welcomes the newbie into her friend group, which includes Gretchen (Katherine Mallen Kupferer) and Janie (Amari Alexis Price). Nancy and the others introduce Margaret to a whole series of new anxieties. For instance, one price of entry into the group requires Margaret to acquire her first bra, and together they perform an iconic exercise from Blume’s book, chanting: “We must, we must, we must increase our bust!” But even as they anticipate the change in their bodies, Nancy mocks Laura (Isol Young), a quiet early bloomer in their class, for maturing early.

Nervous about starting at a new school and impatient about getting breasts and her first period, Margaret takes to speaking to God in her room, praying for things to work out. But Margaret wasn’t raised with a religious foundation, unlike most of her friends. Her father was raised Jewish, and her mother was raised Christian. Both are foreign concepts and, for reasons that become clear later on, her parents have resolved to let their daughter decide what faith she would like to be, if any. Prompted by her teacher to complete a research project that lasts the entire school year, Margaret explores religion, visiting the synagogue with her Grandmother and sneaking into a confession booth after some particularly mean-spirited behavior. The respective ceremonies seem strange and unrelatable; rather, her version of God is the imaginary friend she needs—a good listener and confidant. Craig captures Margaret’s self-styled God and suggests that spirituality is nurturing, while religion is exclusionary. It’s a potentially confronting notion since religions tend not to allow people to draw their own conclusions but instead adhere to a strict dogma. And so it’s refreshing to see Margaret’s brand of independence alive in a mainstream movie.

Like any book adaptation, Craig’s screenplay has additions and omissions. Among the inspired inclusions, Craig expands on Barbara and Sylvia’s roles, offering glimpses into their worlds that hint at the states of womanhood that might await Margaret. With the financial freedoms afforded to the Simons given Herb’s new job, Barbara gives up teaching art classes to become a homemaker. Her struggles to domesticate to New Jersey suburban life prove relatable, awkward, and funny; she vacillates about buying new furniture and almost immediately regrets joining various PTA committees. Sylvia, meanwhile, has a few scenes of loneliness without her family—her daily “To Do” list consists of that day’s crossword puzzle and dusting—but soon finds a new beau. These added flourishes inform the climax, when Barbara’s estranged parents and Sylvia collide over Margaret’s future as Christian or Jewish. Craig brings a dimensionality to these characters that wasn’t there in the book, while also appealing to adults in the audience who might feel Blume’s story is just kid’s stuff.

In other areas, Craig sidelines some of Blume’s thornier and more cynical moments with Margaret, but not without including the book’s jabs at organized religion and the education system’s inadequate lessons for children about the coming onslaught of puberty. But this isn’t a review of Craig’s ability to adapt or meant as a comparison between the two texts, even though it’s a mostly faithful rendering of Blume’s nearly 150-page book. However, Craig renders the cinematic equivalent of Blume’s clear-headed literary presentation, offering a gentle score by Hans Zimmer and functional camerawork by cinematographer Tim Ives. Much of the visual work feels like the result of production designer Steve Saklad and costume designer Ann Roth, who create a convincing 1970s milieu with browns, yellows, and oranges that take the viewer back to this specific time and place. Fortunately, Craig resists the temptation to modernize Blume’s book for today’s audiences. A version of Margaret that’s attached to her smartphone and can read about religion and puberty online is a less dynamic character. What is more, Craig’s witty and sensitive writing would have fallen flat without the right actors, and every role has been ideally cast. McAdams and Safdie have an endearing chemistry; Bates, as you might expect, imbues Sylvia with bombastic and lovable energy; Fortson, charming as Cassie Lang in the first two Ant-Man movies, delivers a textured performance that never feels like a child actor’s work.

In other areas, Craig sidelines some of Blume’s thornier and more cynical moments with Margaret, but not without including the book’s jabs at organized religion and the education system’s inadequate lessons for children about the coming onslaught of puberty. But this isn’t a review of Craig’s ability to adapt or meant as a comparison between the two texts, even though it’s a mostly faithful rendering of Blume’s nearly 150-page book. However, Craig renders the cinematic equivalent of Blume’s clear-headed literary presentation, offering a gentle score by Hans Zimmer and functional camerawork by cinematographer Tim Ives. Much of the visual work feels like the result of production designer Steve Saklad and costume designer Ann Roth, who create a convincing 1970s milieu with browns, yellows, and oranges that take the viewer back to this specific time and place. Fortunately, Craig resists the temptation to modernize Blume’s book for today’s audiences. A version of Margaret that’s attached to her smartphone and can read about religion and puberty online is a less dynamic character. What is more, Craig’s witty and sensitive writing would have fallen flat without the right actors, and every role has been ideally cast. McAdams and Safdie have an endearing chemistry; Bates, as you might expect, imbues Sylvia with bombastic and lovable energy; Fortson, charming as Cassie Lang in the first two Ant-Man movies, delivers a textured performance that never feels like a child actor’s work.

Each character lives and breathes, jumping straight off the page and onto the screen. By disappearing into these roles, the performers allow Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. to transport the viewer into a familiar experience, whether it’s reliving memories from childhood or grappling with the struggles of Margaret’s parents and grandparents. Craig has taken the insular world of Blume’s character and not only given the material cinematic life, but she has also expanded upon it in ways that will appeal to young viewers and adults who cherish their memories with the book. The film reminds us that life is a journey, and maturing is only a small part of that experience, terrifying and awkward though it may be. But best of all, it depicts a character whose emotional maturity results from having the choice to decide her religion and learn about her body in a healthy, supportive way, as opposed to thinking of menstruation as a curse and sexuality as something shameful. The film depicts how that kind of destigmatization has an unchartable positive consequence on a young person. It does so without resorting to soapboxy speeches or schmaltz—just lovable characters in honest situations.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review