Appaloosa

By Brian Eggert |

Ed Harris dusts off and spit-shines all the classical Western regalia for Appaloosa, a voyage back to the archetypes that established the genre as romantic and American, before revisionists asked necessary questions about history and the monstrous nature of the era. The film tells an undemanding story, with heroes and villains well-defined, simple even, but described with enough personality to keep them fascinating. The moral ambiguities driving Westerns in the last twenty years—from Unforgiven to The Proposition—are left at the wayside for a return to traditionalism.

Harris co-wrote, directed, and stars in the film, which proves the legitimacy of the struggling genre in today’s market. Thirty years ago, Westerns drew massive crowds and topped box-office charts, only to slowly dwindle over the last few decades into dust (cue tumbleweed). And while 2007 alone harbored several award-winning examples (The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, No Country for Old Men, There Will Be Blood, 3:10 to Yuma), the genre remains a minority, rarely produced, and often pursued exclusively as passion projects, like Appaloosa.

Before he even finished reading the source novel by Robert B. Parker, Harris claims he knew the material was ripe for film, and his instincts were correct. Certainly, all the appropriate elements are in the mix: dusty towns, rugged trails, hardened gunslingers, and crooked ranchers. The heroes’ motivations are as simple as friendship and law. The villain is simply a villain, and nothing more about him needs to be known. And yet, few of the characters or plot elements feel like tired stereotypes, despite living up to the idealized vision embraced by earlier and more conventional films of the genre.

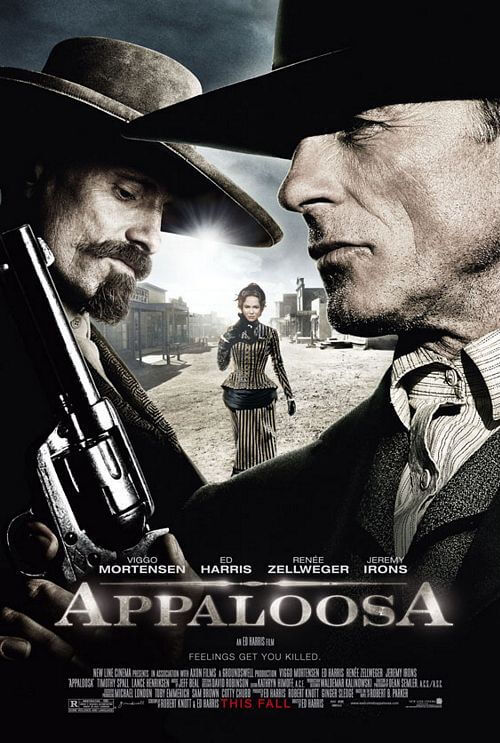

Harris, who directed Pollack in 2000, casts himself in the lead role as Virgil Cole, who, along with his longtime partner Everett Hitch (Viggo Mortensen), sells their talents as lawmen, exorcizing helpless towns of their criminal inhabitants. In other words, they’re hired killers. This is what they do, and not much else. Their unshakable friendship is defined by their time together and the trust built therein. They travel to needy places where the weak populace is pressed under the thumb of whatever local despot thinks he owns the place, and they clean it up. In Appaloosa’s case, the town’s leaders employ Cole and Hitch to rid themselves of Randall Bragg (Jeremy Irons), an outlaw with money and power to burn. When Cole becomes the new marshal, and Hitch becomes his deputy, Bragg’s influence is suddenly challenged after three gang members find themselves in receivership of our heroes’ bullets.

Of course, there’s a new woman in town to turn Cole’s head. This is Allison French (Renée Zellweger), who avoids being either a prostitute or a helpless woman, two of the most common roles for women in Westerns. The type who gravitates to whoever is top dog, she sets her sights on Cole—not that she’s incapable of being drawn by other, more direct men. Hitch, for instance, resists her advances, saying they must resist because they are both “with Cole.” And when Allison later accuses Hitch of propositioning her, Cole simply asks his friend whether it’s true? No, it isn’t. And so, no, it isn’t.

The film’s atmosphere is one of unspoken understanding from the clear bond between Cole and Hitch, who are singular men, both good at what they do, and from their adherence to their implicit code. The gunfights resolve themselves with all the right parties breathing in the end, but they play out with an unnatural poetry. But it’s poetic nonetheless. Meanwhile, the film’s understated humor keeps the tone from brooding about the central conflict. Humorous scenes involving Appaloosa’s chief spokesperson, Phil Olson (Timothy Spall), and shy moments between Allison and Cole, have a surprisingly light air.

The wonderful casting makes the picture. Harris embodies an uncomplicated, straightforward hero whose vocabulary may not be up to snuff, but who knows his work. Mortensen should find another Western role quickly, as he’s perfectly suited for the genre. With bravado subtlety and a perfectly restrained temperament, the Eastern Promises actor takes a role that might otherwise be considered supporting, except he steals every scene, even from the background. Zellweger seems an unlikely choice for a Western damsel, but she plays the part with equal parts blush on her cheeks as dirt on her brow. And Irons’ presence alone, enhanced by his gruff-yet-elegant voice, capably occupies the shark-like gangleader role.

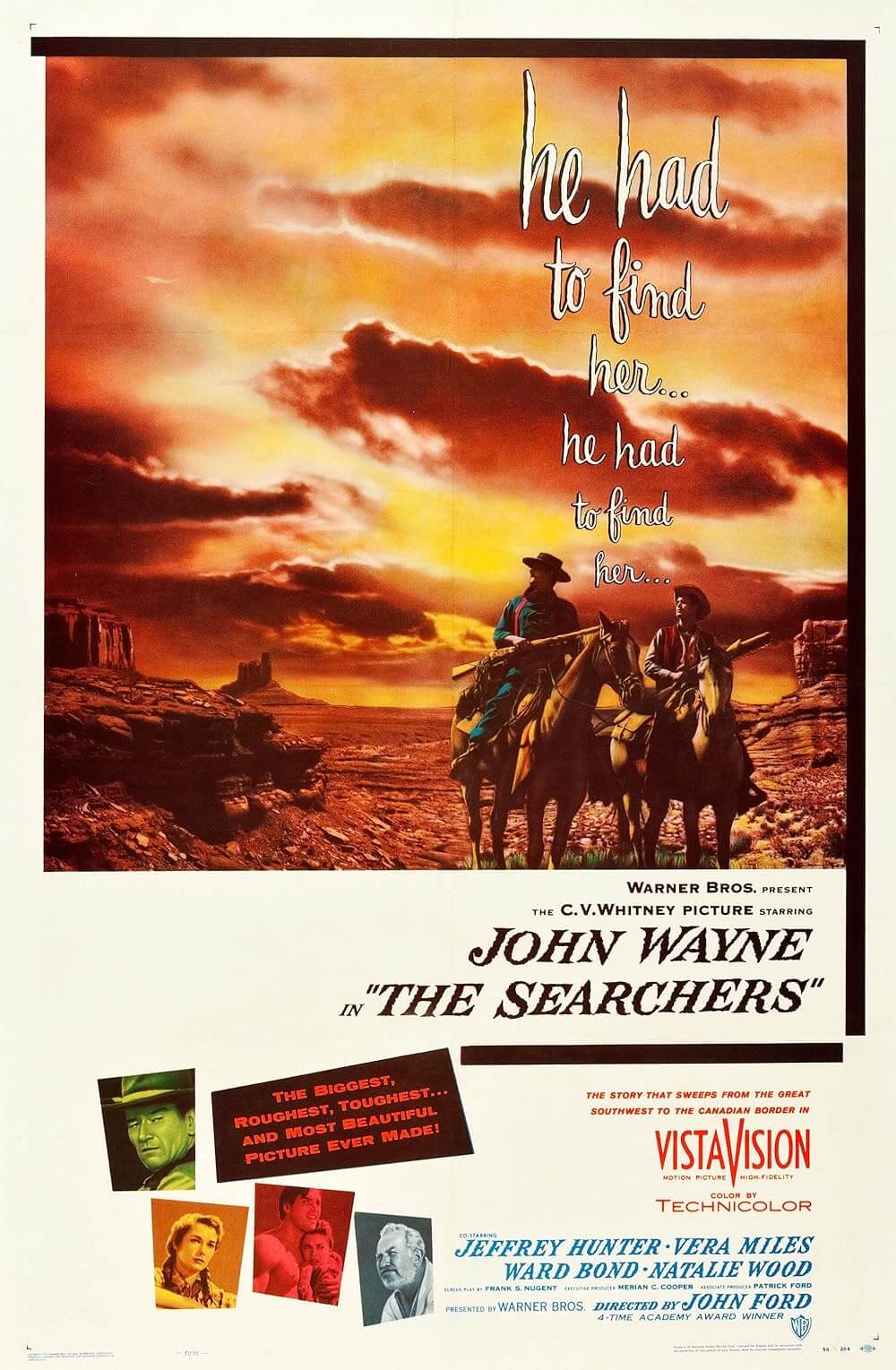

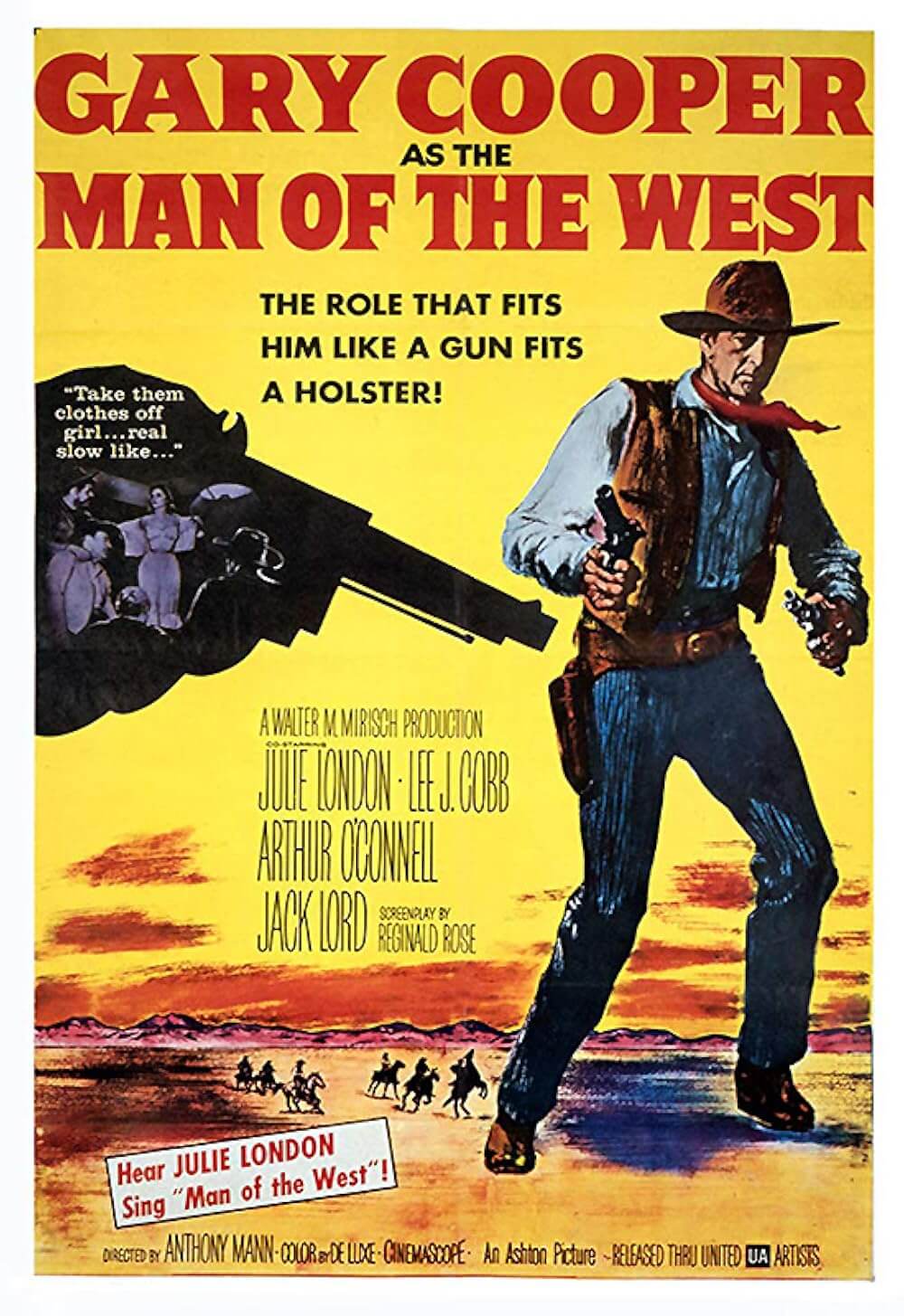

Lacking the cynical judgment over the Old West found in most modern Westerns, Appaloosa proves the idealistic tropes of the genre—long since established by the likes of John Ford, Howard Hawks, and others—still have a place in cinema. However escapist the yarn and those like it may be, such stories maintain an important place in the seemingly forgotten ways of narrative Americana. Seeing Harris foster his film with apparent devotion and love for the Western, a fondness this reviewer openly shares, gives hope that other filmmakers will continue its traditions for a long time to come.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review