Apollo 18

By Brian Eggert |

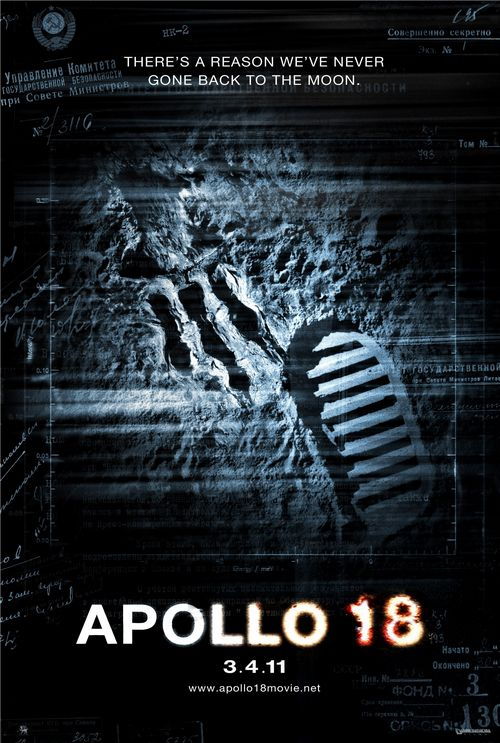

The government doesn’t want you to know that Apollo 17, the 1972 space mission and last known lunar landing sponsored by the United States, wasn’t our last voyage to the Moon. According to the distributors of Apollo 18, there was another, a top-secret mission carried out two years later but kept hidden from the general public. During the mission, eighty hours of footage was shot, capturing the horrifying demise of the mission’s crew. Somehow, someone got a hold of this footage and cut it down to an 86-minute feature. And if you don’t believe the hype, it was all at www.lunartruth.com, a website that’s referenced at the end of the film but then was mysteriously shut down after the film’s debut. If that’s not proof of a conspiracy, what is?

Of course, this is the latest entry into the “found footage” subgenre—an increasingly obnoxious movement where faux documentarians meet their demise through some unnatural force, and we see only scattered bits and pieces of their end through their shaky camerawork. Popularized by The Blair Witch Project in 1999 and repopularized by Cloverfield and Paranormal Activity in recent years, audiences have been inundated with countless samples. Their gimmick may change from rabies-infested zombies to exorcisms to giant forest trolls, but the device is always the same, as are the endings. After all, when someone finds your footage, chances are you didn’t die well; the lesson being not to expect an emotionally satisfying conclusion in any “found footage” movie. Moreover, things like strong characters and rewarding narratives are rarely developed in “found footage” movies, so when the shocks and gross-out moments occur, the audience can’t be blamed for feeling uninvolved.

Early “archival” footage shows us pre-flight interviews with the Apollo 18 crew explaining their mission’s questionable need for security. Before long, John Grey (Ryan Robbins) pilots a command hub in orbit around the Moon, while astronauts Benjamin Anderson (Warren Christie) and Nathan Walker (Lloyd Owen) land on the surface. Their mission to mount a series of scanners is successful, until Anderson notices footprints on the surface. They follow the tracks to a Soviet landing module, not unlike their own, where nearby, they find a dead body of a Russian cosmonaut. Little by little, they learn that whatever happened to the Soviet crew is starting to happen on their own, as Walker comes down with a case of space madness and runs amok on their tiny ship. Shadows pass in front of cameras, screeching static fills the radio, and obscure objects move in the distance, inciting curiosity that goes unanswered. Still, you’ll see more of the unwanted creatures here than you did in The Blair Witch Project. And, to be sure, Mission Control in Dallas proves to be no help once they realize the crew is contaminated.

Spanish director Gonzalo Lopez-Gallego, under the supervision of producer Timur Bekmambetov (Wanted), uses a diverse bag of video trickery and production design to heighten the story’s pretense, his verisimilitude easily the movie’s most successful element. Grainy footage looks to be shot with antiquated cameras, some of it hand-held footage and some security tape from the craft’s CCTV system. Static interruptions and an overall fuzzy presentation have us squinting to make out details when unfriendly creatures begin to emerge, and swerving camera movements by the panicked heroes don’t help much for clarity’s sake, either. And though endless jump cuts are understandable, the editors who supposedly chopped together the extensive footage could have cut around sudden film stock burns and distorted imagery. Then again, it must be difficult to concern oneself with concise editing when the government is after you.

Anyway, we’re left to question how the footage ever made it back home from space. Chances are we’ll find out next fall when, inevitably, a movie about Apollo 19 opens. This is all but definite, as “found footage” movies have a high rate of profitability, seeing as they’re made using deliberately cheaper equipment for an intended low-quality polish. Made for around $5 million in Vancouver, you can be sure Apollo 18 will earn a profit on opening weekend even with a half-hearted box-office response. The same audiences who made Paranormal Activity and Quarantine hits will no doubt feed this release the modicum of reaction it needs to justify its existence, even if the familiar setup does not.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review