Apollo 11

By Brian Eggert |

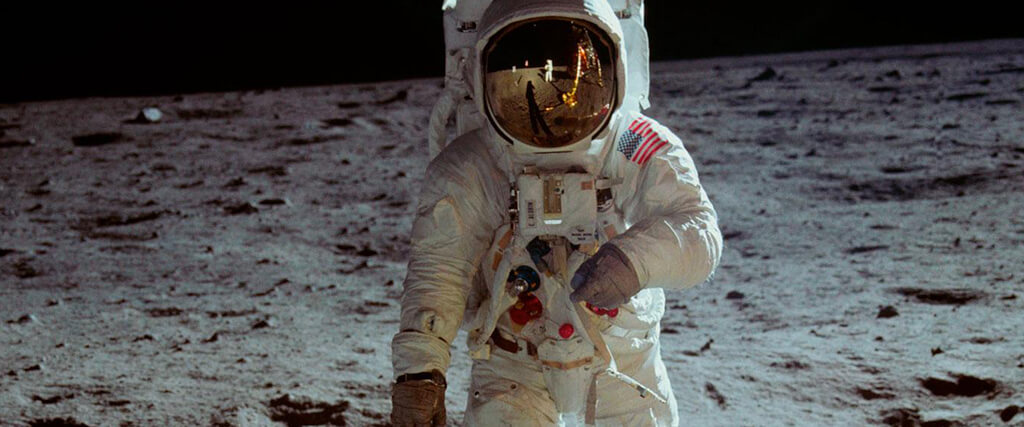

Astronauts who have walked on the moon or returned from an orbital spaceflight often talk about how minuscule the Earth looks in the ocean of black space. They come back with their perspectives altered. And it’s not because math tells them that our planet is just a modest part of the solar system, a speck in the Milky Way galaxy, and not even a consideration in the infinite universe. But instead, they’ve seen our crystal blue orb from an angle available only to a chosen few. They can see the Earth is a place without borders, and in the grand scheme of things, the concerns of human beings are quite small. The documentary Apollo 11 gives the viewer a sense of our smallness in relation not only to the great expanse of the stars, but also in relation to the enormity of the machines, technology, and vision that took us to Earth’s moon. Hundreds of engineers, designers, controllers, physicists, bolt-tighteners, and countless other support teams worked together to send Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins to the moon. Apollo 11 pays tribute to everyone involved by bringing this nearly 50-year-old event to vivid life.

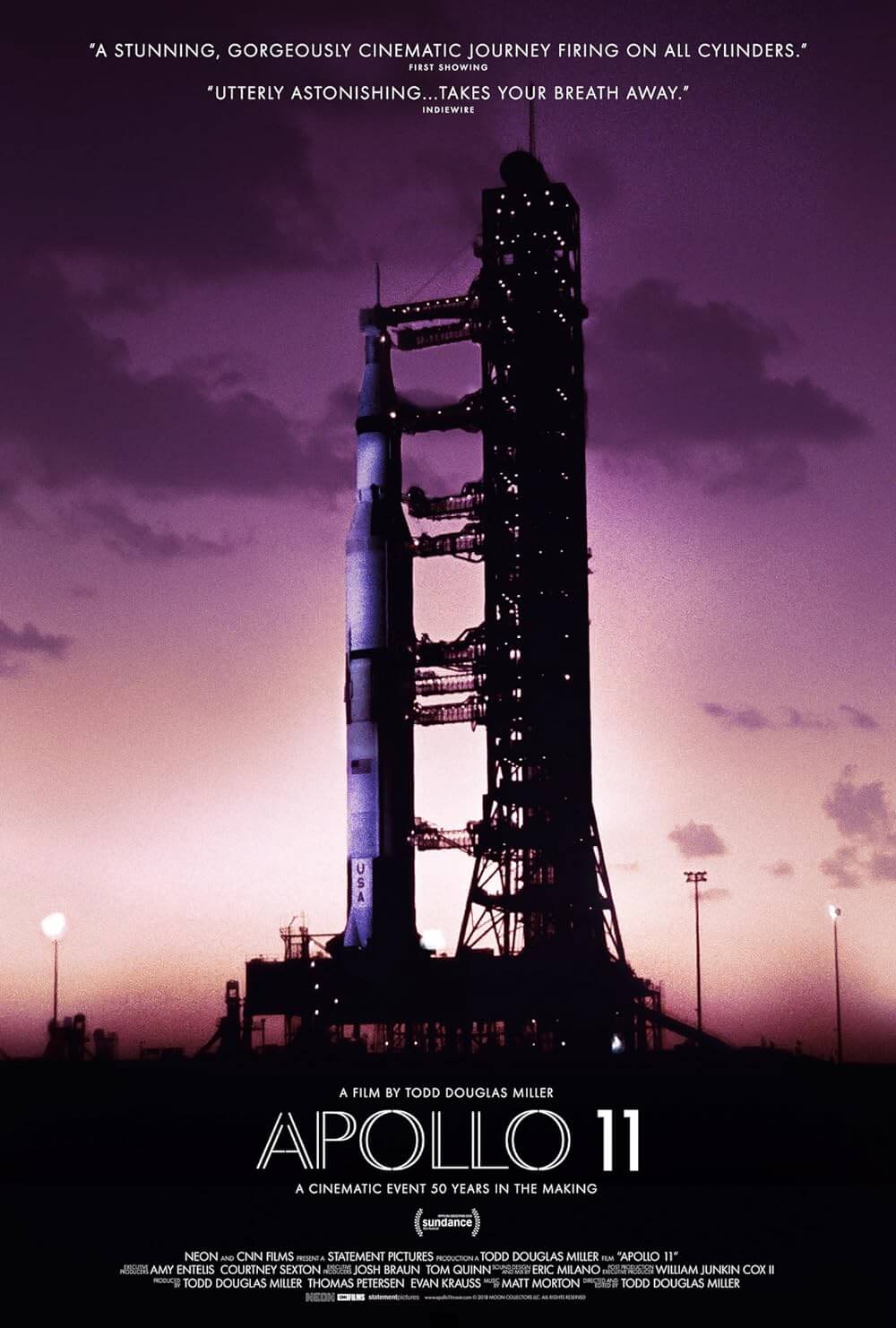

Directed and edited by Todd Douglas Miller, the film is a result of a chance discovery by NASA and the National Archives. They happened to find large format, 70mm archival footage in storage, shot by NASA and long-since-forgotten. Miller took the newly restored footage, which looks better than most Hollywood productions of the era, and combined it with other sources filmed in 16mm and 35mm, as well as footage from inside the shuttle and the astronauts’ body-mounted cameras. Miller arranged the footage without any detailed explanation of where it came from (as many recent documentaries often end up being about the process of shooting the documentary). He also avoids inserting a narrator or witness accounts to explain what we’re seeing. The story of Apollo 11 unfolds through observational images, vintage news coverage, and on the faces of those involved, with only a little help from original, explanatory black-and-white animations that draw from the look of Asteroids.

The first shots show a tank-like vehicle hauling the Saturn V rocket to the launchpad. It moves slow, and technicians walk by on foot. It’s interesting to think that not only did NASA have to build a rocket to the moon, but they also had to design a vehicle sizeable enough to transport the rocket. Dozens of the behind-the-scenes images like this glimpse the other people behind the launch, illustrating what an enormous human endeavor this was and how significant the smallest roles could be. Just a few minutes before the launch, a technician must tighten a few bolts on the shuttle to prevent a disaster. Elsewhere, we see endless crowds of people gathered nearby, hoping to snap a few photos or shoot a home movie of the launch. Millions of others watched at home, united by their hope of exploring this new frontier. It’s a touching demonstration of what people can achieve when they’re working together toward the future instead of infighting. But we have short attention spans. Once the launch commences and the eight-day journey begins, Apollo 11 reminds us that Americans were temporarily distracted by the Chappaquiddick scandal.

The details of the journey to the moon and back will be familiar to those versed in earlier docs about the subject, such as Theo Kamecke’s Moonwalk One (1972) or Al Reinert’s more stylish For All Mankind (1989). Or if you prefer, the dramatization in last year’s First Man (2018). Miller borrows a page from Brian Eno’s electronic score in Reinert’s film and applies synth-laden music by Matt Morton, which sounds vaguely like montage music in a sports movie about robots. Despite the familiarity of it all, Apollo 11 still manages to create a sense of awe and wonder. Consider the sequence when Armstrong and Aldrin touch down on the moon’s surface. Onscreen, two sets of digital numbers count down the amount of remaining fuel and the seconds before the landing. The team behind Apollo 11 had perfected these calculations so that the Eagle lander would touch the surface with about a second of fuel left. And as our eyes move between the two digital counters and the image of the lander’s descent, we barely breathe, despite knowing the outcome.

It’s in small and forgotten details such as this—or mission control’s account of the astronauts’ heart rates at points in the flight—that bring Apollo 11 back from the distant past and into reality with a human urgency. The film, best viewed on the biggest screen available to get the full effect of the mission’s size and scope, reminds viewers of a time when humanity used to think big. When John F. Kennedy gave his famous “We choose to go to the moon” speech in 1962, he set his sights on what at the time was impossible, and yet people pulled together to make it happen. This is an incredible account of that mission, its footage unbelievably pristine and often quite beautiful. And, without actively engaging in modern-day commentary or relevance, Apollo 11 is nonetheless a reminder that the most monumental frontiers reside beyond our planet’s surface.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review