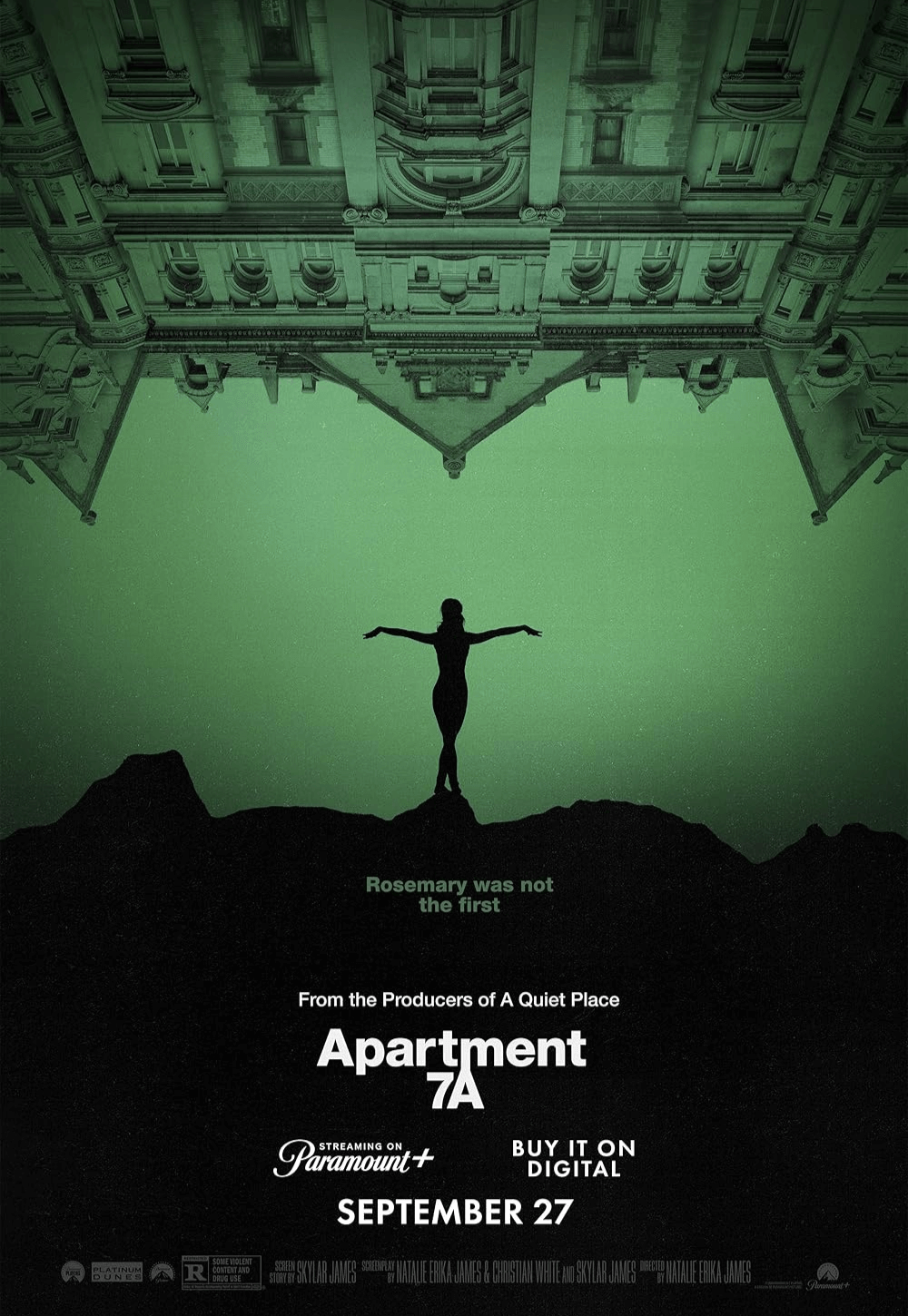

Apartment 7A

By Brian Eggert |

(Natalie Erika James’ Apartment 7A will debut on Paramount+ on September 27, 2024.)

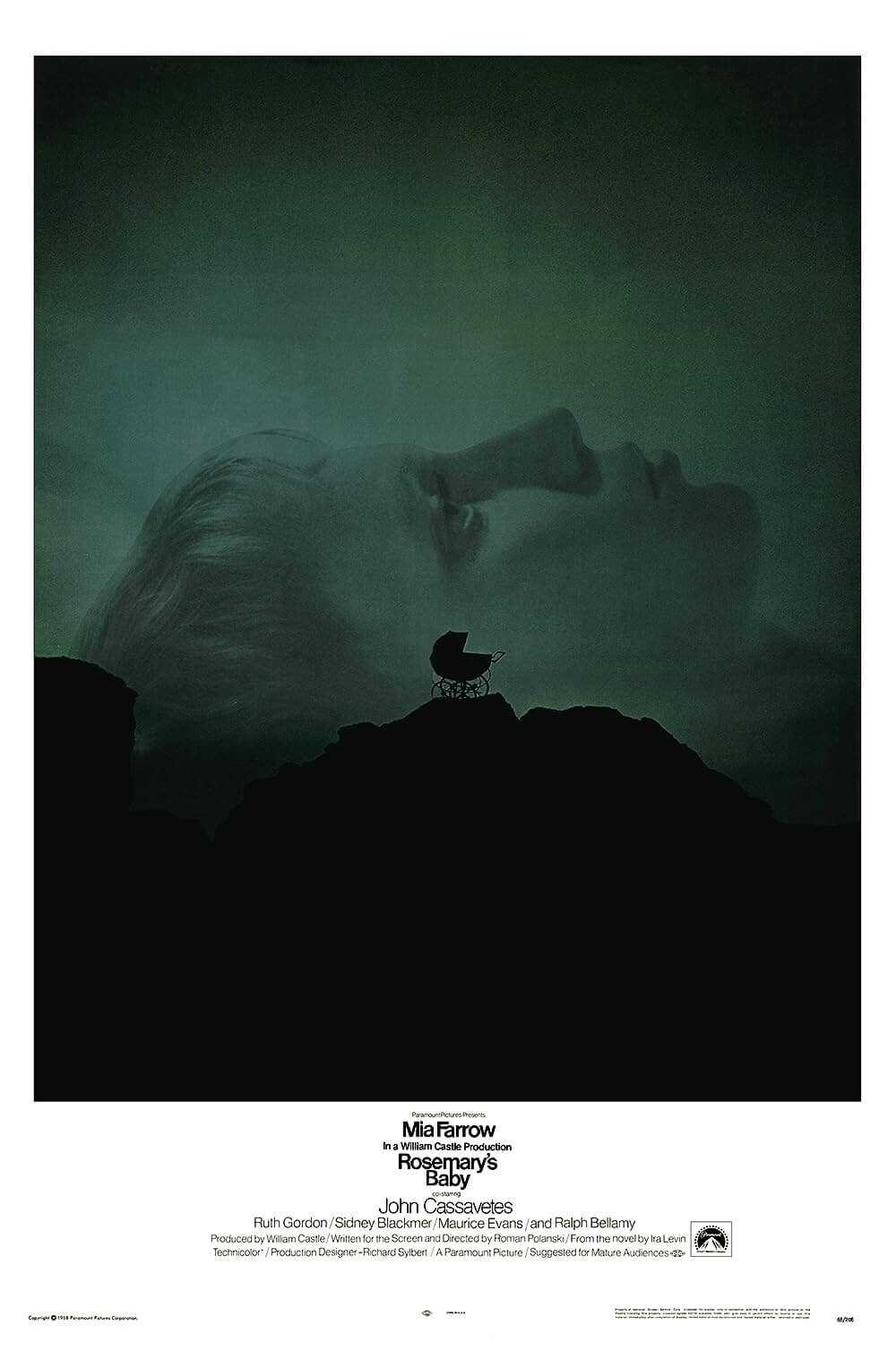

I have reached my limit with this kind of movie. After seeing multiple examples this year and countless others in recent years, I can take no more of them. It’s the legacy sequel or, in the case of Apartment 7A, the prequel designed to capitalize on a classic. Here, the movie accounts for the events before what occurs in Rosemary’s Baby (1968). Part of the problem with these sorts of films is that they’re less interested in telling a story than filling in gaps, answering questions left by the original, and demystifying whatever mysteries remain about their predecessors. What frustrates me most is that, apart from some particulars, many of them resolve to tell the same story as the original, revealing that the events are part of a larger pattern. Many of them are capably made by indie directors hoping to prove their worth to studios and land a larger project next. And even though they boast confident direction and often feature memorable performances, they’re devoid of new ideas and serve only to reinforce brand awareness.

Several franchises have engaged in this trend, mainly because studios want a sure thing based on traceable evidence. If it worked in the past, it might work again—that’s their logic, anyway, justifying empty retreads and ostensible remakes designed to look like sequels or prequels. Examples appear in dozens of franchises, including Star Wars, Beetlejuice, Ghostbusters, Creed, TRON, The Matrix, Halloween, Pet Sematary, The Omen, and Jurassic World. The problem isn’t that these movies tell the same stories on repeat; they tell them without disguising their sameness or bringing anything substantially new to the mix. Occasionally, a filmmaker might produce a legacy sequel or prequel that does something altogether different. When George Miller continued his Mad Max franchise with a sequel, Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), and then a prequel, Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga (2024), he continued to redefine the franchise he started decades earlier by never repeating himself and expanding on his mythology. But that’s the rare exception.

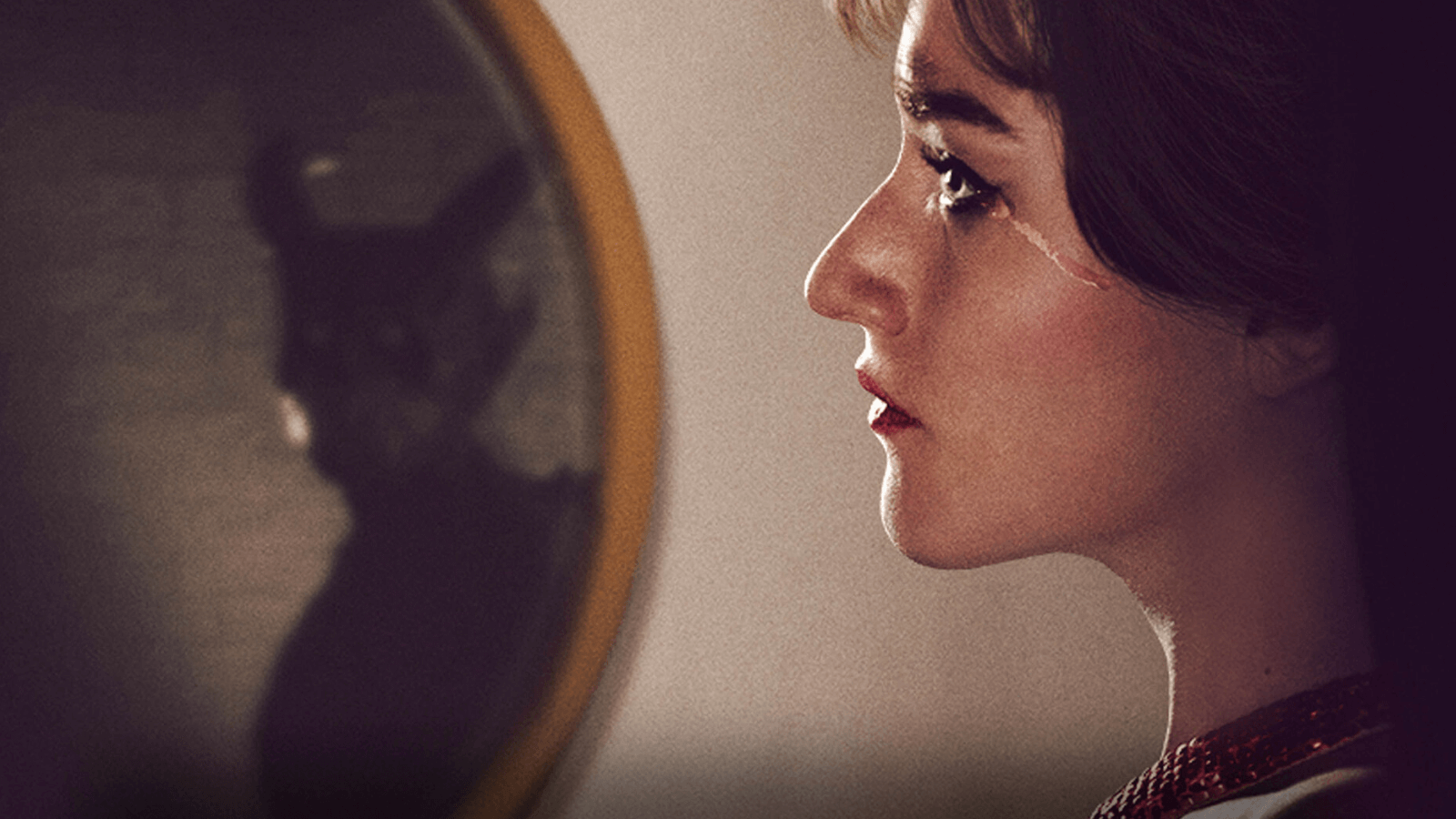

Apartment 7A explores Terry Gionoffrio, the young woman from Rosemary’s Baby who had the attention of the old Satanist couple, Minnie and Roman Castevet, before killing herself early in the film. The viewer enters the movie with the foreknowledge of Terry’s fate, which neutralizes much of the suspense. It’s an experience less about answering the question “What will happen next?” than “How will we get there?” However, even when limited by where the story will go, a prequel can surprise you. But that’s not what happens in Apartment 7A. Julia Garner plays Terry, an aspiring Broadway dancer from Nebraska who, in the first sequence, has a devastating accident during a performance. She’s left with a limp and a slim chance of a career on the stage. With Terry on the verge of being kicked out of her apartment, Minnie and Roman (Dianne Wiest, Kevin McNally) give her a place to stay and help her earn the favor of a famous producer (Jim Sturgess).

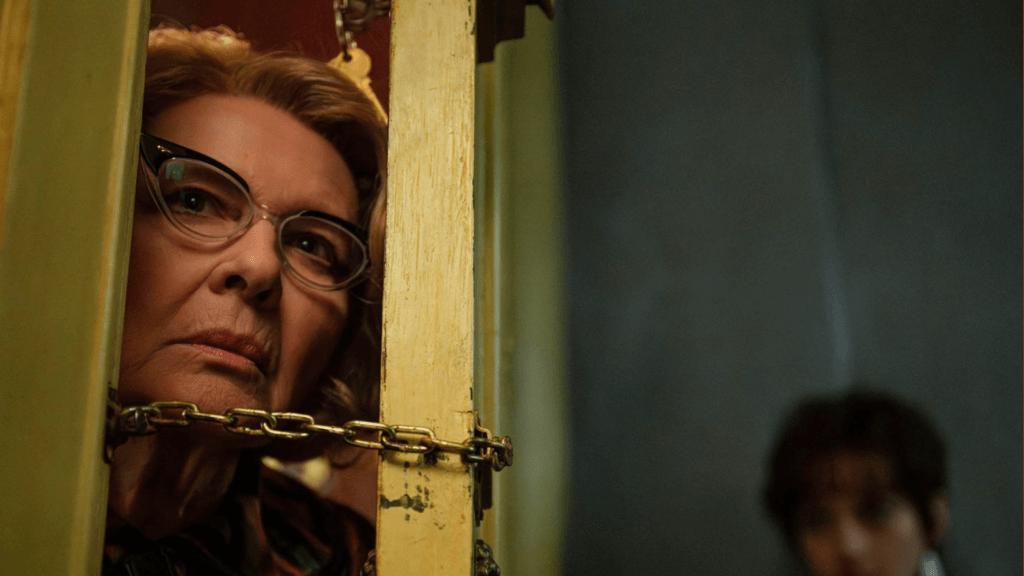

Director Natalie Erika James (Relic, 2020) worked alongside Christian White and Skylar James on the script, which competently brings established characters back to life. Wiest and McNally give particularly attuned performances as Minnie and Roman, delivering often uncanny impressions of Ruth Gordon and Sidney Blackmer. Garner has more to invent here, as Terry was practically a nonentity in the original film, leaving more room for the creative development of her character. Garner inhabits the role well, playing her as defiant, independent, and determined. She’s an amalgam of Rosemary and Guy Woodhouse, serving as both a mother and a stage professional whose career takes a turn for the better after befriending the Castevets. Still, known as “the girl who fell” after her stage accident, Terry’s label is an unsubtle allusion to her eventual fate, and she feels pulled along by the narrative requirements rather than a participant in her story. Though, in the film’s climax, James recontextualizes Terry’s death, making her eventual suicide less a tragedy than a reclamation of her power, whereas our understanding of her death in Rosemary’s Baby suggested she was a mere victim.

Director Natalie Erika James (Relic, 2020) worked alongside Christian White and Skylar James on the script, which competently brings established characters back to life. Wiest and McNally give particularly attuned performances as Minnie and Roman, delivering often uncanny impressions of Ruth Gordon and Sidney Blackmer. Garner has more to invent here, as Terry was practically a nonentity in the original film, leaving more room for the creative development of her character. Garner inhabits the role well, playing her as defiant, independent, and determined. She’s an amalgam of Rosemary and Guy Woodhouse, serving as both a mother and a stage professional whose career takes a turn for the better after befriending the Castevets. Still, known as “the girl who fell” after her stage accident, Terry’s label is an unsubtle allusion to her eventual fate, and she feels pulled along by the narrative requirements rather than a participant in her story. Though, in the film’s climax, James recontextualizes Terry’s death, making her eventual suicide less a tragedy than a reclamation of her power, whereas our understanding of her death in Rosemary’s Baby suggested she was a mere victim.

That admirable touch aside, the blueprint James and company adopt follows Rosemary’s Baby beat by beat. There’s another drugging, another hallucinatory rape by the devil, another short haircut, another painful pregnancy, another series of unhelpful consults with a Castevet-approved obstetrician, another tannis root necklace, another hidden passage in the apartment, another knife-wielding confrontation, and another climax with a group of occultists shouting, “Hail, Satan!” I could go on. Even when Apartment 7A introduces a new idea not borrowed from Rosemary’s Baby, it’s a derivative one. Take when Vera (Rosy McEwen, from 2023’s Blue Jean), a mean and competitive dancer in Terry’s latest stage production, is taken out by supernatural forces: her body contorts in horrible ways, but it’s less a terrifying moment that a distractingly familiar one to a similar sequence in Suspiria (2018). Although bereft of original ideas, the film has been well assembled by James, with textured cinematography by Arnau Valls Colomer and transportive production design by Simon Bowles, most evident in the elaborate, expressionist Broadway production scenes.

At the very least, Apartment 7A uses its story to comment on present-day anxieties about abortion and pregnancy in the post-Roe environment. The initial Roe v. Wade decision was made in 1973, five years after Rosemary’s Baby debuted, but Rosemary Woodhouse never considered an abortion. However, Terry seeks to terminate her pregnancy from an underground abortionist, and the result speaks to the lack of autonomy women have in an America without abortion access, where religious beliefs of one group limit the rights of all. Apartment 7A’s most daring idea is equating the Satanists who prevent Terry from getting an abortion with the Christians in America today who attempt to force their values concerning abortion access on everyone else. In 2024, a year full of movies about nightmarish pregnancies in horror (see The First Omen, Immaculate, Alien: Romulus, and even Beetlejuice Beetlejuice), Apartment 7A manages to have a perspective on this topic. Unfortunately, that’s where its novelty ends.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review