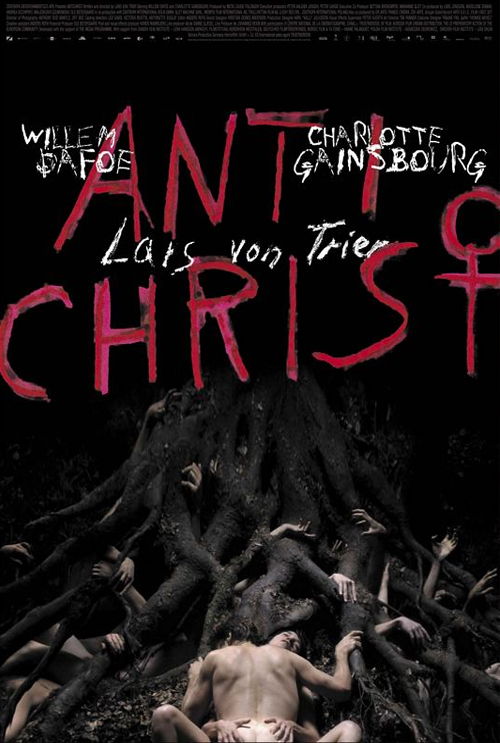

Antichrist

By Brian Eggert |

Lars von Trier’s Antichrist amounts to little more than artistic masturbation; there’s even a bloody and unnecessary scene in the film that demonstrates this. As the most talked about motion picture at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, it has divided audiences and critics between utter revulsion and declaring it a work of pure genius. Yet the result operates in such an obvious manner, it’s easy to see right through von Trier’s desperate aim to incite a reaction, whatever that reaction proves to be. While commendable for stimulating discussions about film as art, the work itself resists an emotional connection through its profound self-consciousness. The Danish director made the film following an admittedly prolonged depression, but being gloomy is a gross understatement if this is the result. While von Trier was in this sad place, he said that he thought he’d never make another film again. Some will wish he hadn’t. Von Trier has always promoted himself as much as his films, if not more so, and he willingly made his own misery known for the sake of this film, a horror picture about a world wherein Satan created Nature. Be it in his heavily publicized “Dogma 95” movement or proclamations of his own greatness, von Trier makes certain that he remains the centerpiece. His films like Breaking the Waves and Dogville have gone out of their way to be grotesque or unpleasant or controversial, while their writer-director stands on the sidelines enjoying the ensuing attention. Antichrist is no different.

From the outset, the film wants to be offensive. In the beautifully shot black-and-white monochrome prologue, von Trier shows the film’s two characters, known only as He (Willem Dafoe) and She (Charlotte Gainsbourg), having lustful intercourse in slow motion. As the film reaches NC-17 extremes within the first shots, in the next room, their curious child explores an open window and the snow gently falling outside. The boy climbs up onto the windowsill, slips, and falls to his death on the street below. This occurs at the same moment that his mother achieves orgasm as she watches her child climb out of the window. Grief- and shame-stricken in the hospital, she is overwhelmed by sorrow. Her husband, being an experienced therapist, takes her off prescribed medications and tells her that she must face her grief and fears. She feels most vulnerable in the woods surrounding their cabin, located in a forest called Eden no less, and so there they retreat to work through the loss of their child.

Titles with names like “Despair (Gynocide)” and “The Three Beggars” precede the film’s various chapters, each of which progresses into more and more disturbing territory. Misty forests create an eerie atmosphere around the pain-is-pleasure couple, who together try to expose her fears about Nature to conquer her angst. Strange and symbolic Nature imagery reminds them of their loss: A baby bird falls from its nest onto an ant hill, and its mother swoops down to eat it on a nearby perch. Acorns representing the tree’s children fall on their cabin’s tin roof, an audible reminder of their tragedy. But then a mangy fox appears and announces, with von Trier’s voice, that “Chaos reigns”—this scene inspired unintentional laughter. It seems like an arthouse parody meant to be ironic. Except it’s not.

By the time von Trier’s misogynistic script has Gainsbourg’s character proclaiming that women are the nature of evil, this critic gave up on deciphering the film’s meaning, realizing that von Trier only wanted to upset his viewers. But at this point, the director was just getting started. Using a combination of religious iconography, a fuzzy narrative, and graphic sexual violence, the film twists into a gory procession of horrible acts. She smashes He’s sexual organ with a block of wood and ejaculates him to come blood; then she drills into his leg with a hand-cranked tool, affixing a weight to his leg through the bloody hole. Von Trier probably wanted to make Dafoe’s character a contrary version of Christ and have him endure a series of trials before the film’s celestial finale. No doubt a religious parallel exists in every scene. But von Trier isn’t interested in your ability to decode his symbolism; he wants to push you into an emotional response.

When von Trier places the camera between Gainsbourg’s legs to capture her slicing off her clitoris with a pair of scissors, makeup effect though it may be, von Trier knows people will talk. He wants it. His film depends on it. There’s a level of “torture porn” at work here, an exhilaration from having the director answer our lingering question: “How far will he go?” As emotional angst translates into sadistic physical punishment between the characters, von Trier captures these moments in gruesome detail. His camera, much like Eli Roth’s in Hostel, does not shy away in the least. He wants sexual and violent detail in the film because it’s through those methods that his characters communicate. Seeing these acts in explicit reality, however, leaves absolutely nothing to the imagination. While the director dares to confront his audience, through his explicated visuals he leaves nothing for us to contemplate.

This is an extremely well-acted film. If it’s watched at all, it should be done so for the acting. Gainsbourg won a prize at Cannes for her performance, and she deserves an Oscar nomination for being incredibly fearless onscreen. She’s brilliant at portraying the anguish of her character, making her desolation come across with pitch-perfect reality. Dafoe, meanwhile, feels dialed down in comparison, but his presence alone can keep an audience involved. Von Trier shot the picture digitally with a Red One camera, lending the outcome a shaky, really there feel that supports the actors but not the more fantastical elements of the story. Then again, the story isn’t the director’s concern.

Writing a somewhat objective analysis for Antichrist has proven a challenge because von Trier goes so maniacally out of his way to poke and prod his audience by whatever means necessary. He does this on a very personal level, no matter the viewer. Whether his goading incites a reaction of sheer revulsion or artistic admiration depends greatly on the viewer. He must, however, be praised for stimulating a fierce reaction. No one will watch this film and dismiss it. It’s impossible not to talk about it. It must be discussed and debated. When audiences can endure so much Hollywood fodder without a word, von Trier, provocateur though he may be, has inspired fervor. How often can you say that about the majority of movies today? That being said, von Trier takes blatant, transparent steps to be provocative. He even proclaimed himself “the greatest director in the world” at Cannes. Making such a statement to that crowd is just begging for a reaction. His film begs for a reaction too, but it leaves the viewer feeling curiously empty afterward because it’s so evident that he’s trying to goad us. And besides the impressive performances therein, Antichrist achieves nothing beyond forcing us to discuss it. In some respect, that’s admirable, since the filmmaker did exactly what he set out to do. But from another perspective it’s completely contemptible, as though the director had nothing to say, so he resolved that he would make the audience speak for him.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review