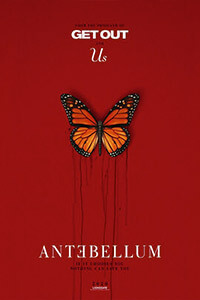

Antebellum

By Brian Eggert |

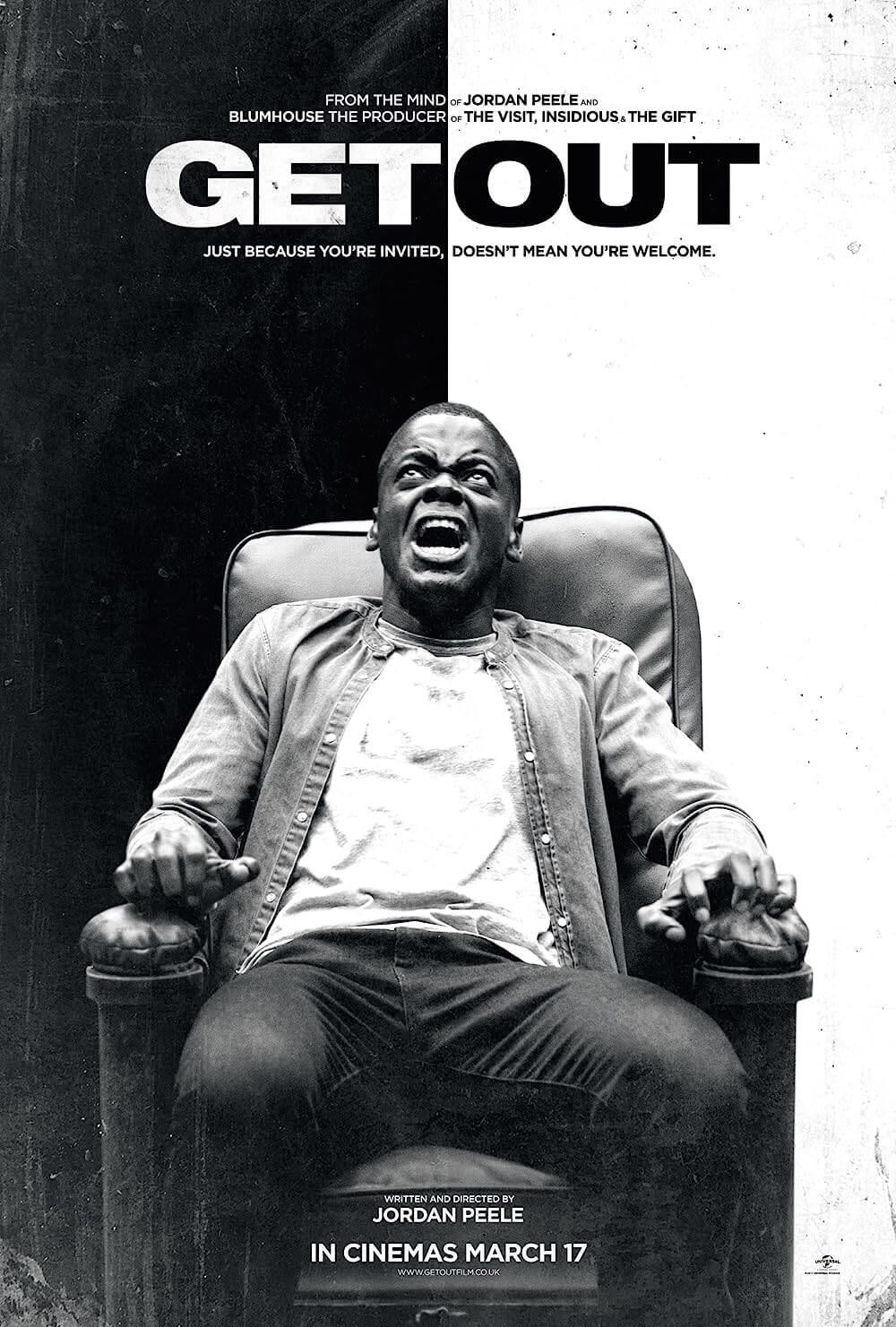

The trailer for Antebellum raises questions with its juxtaposition of images and timeframes. We see glimpses of Janelle Monáe in a cotton field on a Southern plantation. We see despair on the faces of slaves, and a woman of color who runs from her captors. But at the same time, an airliner flies overhead, and a 9-1-1 operator asks, “What’s your emergency?” A moment later, the trailer shows the stylish and beautiful Monáe in modern garb, clearly living in the twenty-first century. Is she experiencing a past-life scenario? Is she transported back through time? What’s happening in this film? We are intrigued. But the answers to these questions don’t become clear until more than half-way through Gerard Bush and Christopher Renz’s fascinating debut, an ambitious horror film that feels inspired by M. Night Shyamalan’s The Village (2004) and Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017). We realize later that the trailer gives away the film’s biggest surprise. And because what works best—and worst—about Antebellum is wrapped up in its secrets and how the writer-directors deal with them, this review will discuss the story and its various twists in detail.

Antebellum opens with a contrast of brutal violence and Malickian images captured at the magic hour. Cinematographer Pedro Luque weaves through a Civil War-era plantation with an impressive extended shot, using the visual beauty of a sunrise to illuminate the cruelty of slavery—recalling the most difficult moments in Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave (2012). When a woman tries to escape, the film dramatizes her dash away from Confederate soldiers with punishing slow-motion, as Captain Jasper (Jack Huston) hunts her down and delights in the process of lassoing her neck and shooting her. The break-out was arranged by Eden (Monáe), a rebellious woman who “belongs” to the camp’s leader, known only as Him (Eric Lange)—a man who beats her and orders her to say her slave name. As the story proceeds, we learn that the Confederate Army camp does not allow its slaves to speak unless spoken to, and their punishments are severe, including death and cremation in a brick box called “the shed.” But the arrival of new slaves, among them the pregnant Julia (Kiersey Clemons), forces Eden to watch as those around her are dehumanized and tortured at the hands of her white captors.

All at once, Monáe’s character wakes up in a modern setting and frets to her husband (Marque Richardson) that she had another bad dream. Now her name is Veronica Henley. She has a young daughter (London Boyce), and she’s a well-known lecturer with a Ph.D. in American Constitutional History. But what has happened here? Were the previous forty-five minutes in a convincing Civil War film just an elaborate dream? It’s unclear, and the film continues to follow Veronica on a trip to Louisiana to give a talk about sisterhood and confronting history. Later that evening, she enjoys a night out with her BFFs (Gabourey Sidibe and Lily Cowles) and some much-needed comic relief. But at the same time, a snakelike Jena Malone, who appears to savor every moment onscreen with devilish pleasure, follows Veronica and sneaks into her hotel room—the “Jefferson Suite” no less. We know Malone’s character, the daughter of a prominent Senator, spells trouble for Veronica because, in the earlier timeline, she presided over the plantation. And when Malone and Huston kidnap Monáe by pretending to be her Uber driver, the twist reveals that everything we’ve seen thus far takes place in the present.

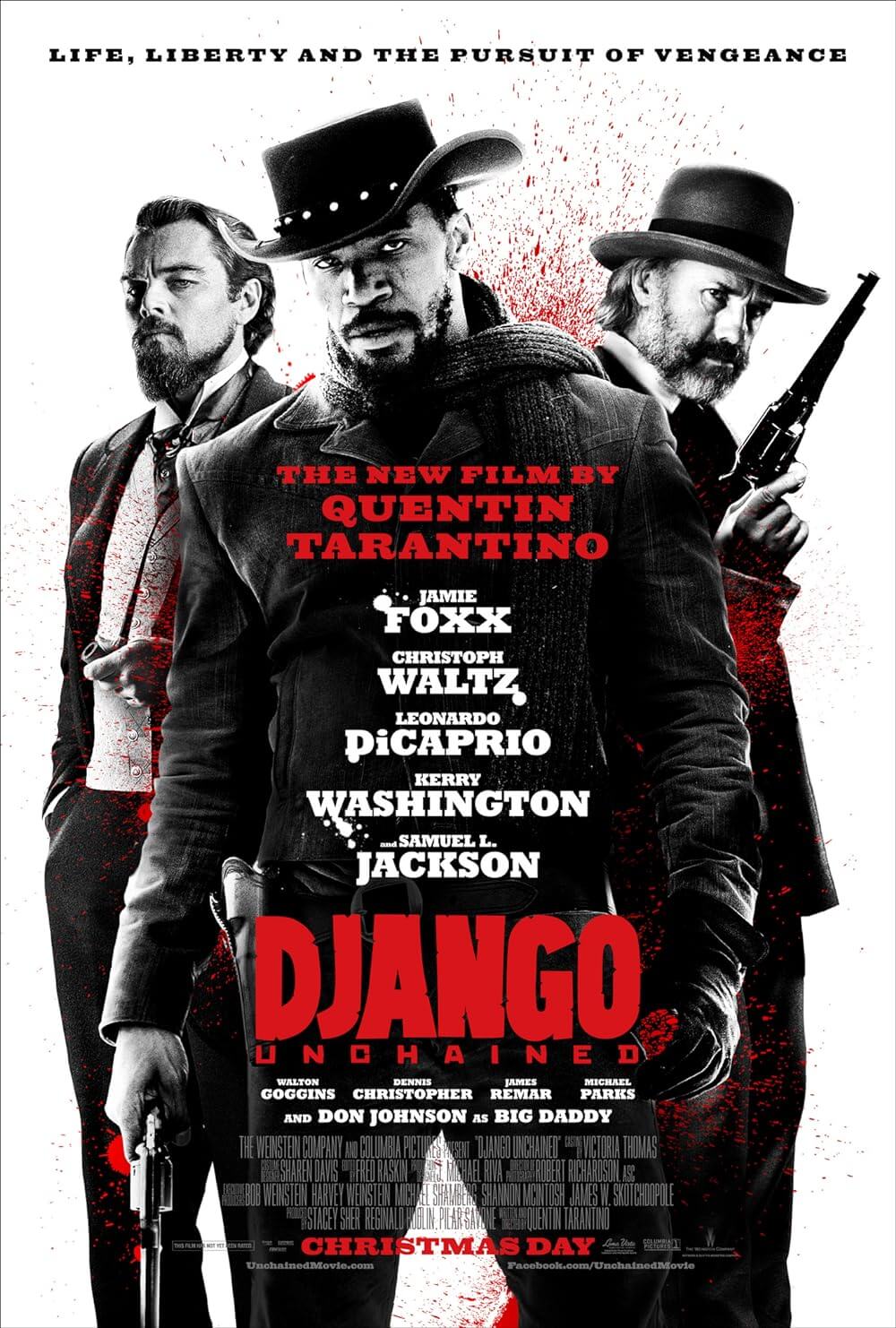

The screenplay by Bush and Renz has an effective structure, revealing in due time that a group of modern white supremacists has recreated the pre-emancipation conditions of slavery in a Civil War reenactment park. They snatch prominent Black intellectuals, including Veronica, brand and shackle them in some cases, and force them into slavery. The strength of this idea alone is enough to make Antebellum a horrifying concept-of-a-film. But their screenplay falters when it uses intellectual rhetoric about the persistence of American racism and slavery into the film’s dialogue. Veronica talks about intersectionality and the patriarchy in ways that eliminate subtext, making the commentary a blunt object that cannot be ignored. Somehow, Bush and Renz didn’t trust their powerful imagery and clever plotting to communicate their message, making Veronica’s discourse feel overstated. But their worst offense comes at the end. After injecting lofty ideas about men and especially women of color taking control of their identities, the film descends into a dull horror show. The final sequence of gristly, cathartic violence turns Veronica, who has been assigned the name Eden, into a ruthless badass who unleashes eye-for-an-eye retribution on her captors. It’s meant, I think, as a counterbalance to the opening scene; however, the tone becomes almost exploitative in a manner befitting Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained (2012)—a tone Antebellum hasn’t earned.

The screenplay by Bush and Renz has an effective structure, revealing in due time that a group of modern white supremacists has recreated the pre-emancipation conditions of slavery in a Civil War reenactment park. They snatch prominent Black intellectuals, including Veronica, brand and shackle them in some cases, and force them into slavery. The strength of this idea alone is enough to make Antebellum a horrifying concept-of-a-film. But their screenplay falters when it uses intellectual rhetoric about the persistence of American racism and slavery into the film’s dialogue. Veronica talks about intersectionality and the patriarchy in ways that eliminate subtext, making the commentary a blunt object that cannot be ignored. Somehow, Bush and Renz didn’t trust their powerful imagery and clever plotting to communicate their message, making Veronica’s discourse feel overstated. But their worst offense comes at the end. After injecting lofty ideas about men and especially women of color taking control of their identities, the film descends into a dull horror show. The final sequence of gristly, cathartic violence turns Veronica, who has been assigned the name Eden, into a ruthless badass who unleashes eye-for-an-eye retribution on her captors. It’s meant, I think, as a counterbalance to the opening scene; however, the tone becomes almost exploitative in a manner befitting Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained (2012)—a tone Antebellum hasn’t earned.

Some critics have questioned what the filmmakers hoped to say with their use of Faulkner’s famous line from Requiem for a Nun, “The past is not dead. It’s not even past.” Antebellum opens with the quote, and it’s referenced again later in the dialogue. Bush and Renz suggest that racial hatred and violence has not been neatly packed away into the history books. Oppression and inequality remain ever-present in American culture, and certain groups actively pursue a racial hierarchy. The film explores this idea in a nightmarish way. It reminds us that the Civil Rights Movement did not end racism, as recent examples from the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville to George Floyd’s death to the disturbing implications of Trump’s “Patriotic Education” initiative have revealed. Antebellum uses the guise of a horror film, much in the way Get Out did, to reveal a potent strain of racism not only festering underneath the surface but also emerging in everyday life in shocking ways. When Veronica and her friends have a ladies’ night out, their interactions with a white concierge and hostess show behaviors that barely conceal a prejudice at work. And the leader of the modern-day slave camp uses language echoed by today’s white supremacists: “This is the only hope we have of retaining our heritage.”

Although the film has a clear purpose, some of its methods remain questionable. To be sure, Bush and Renz have an unsubtle approach, and the violent climax, punctuated with Monáe wrapping her captor in a Confederate flag and burning him alive, or Malone’s head cracking on a statue of Robert E. Lee, is about as blunt as it comes. Instead of allowing the basic story to symbolize what they wanted Antebellum to represent, the filmmakers underline the point with broad language and unmissable imagery. Moreover, the trailer and official synopsis provided by the distributors at Lionsgate spoil the film’s biggest secret. Watching the first act unfold at a plantation, I kept admiring how committed Bush and Renz were to immersing me in a false setting. Yet, I could not help but feel the ache of having what might have been a confronting switcheroo spoiled for me by the trailer. But despite these nitpicks, and some general disappointment over how much better it might have been had the filmmakers exercised restraint, Antebellum is confidently made and thought-provoking, and further proof that Monáe is a terrific screen presence.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review