Another Earth

By Brian Eggert |

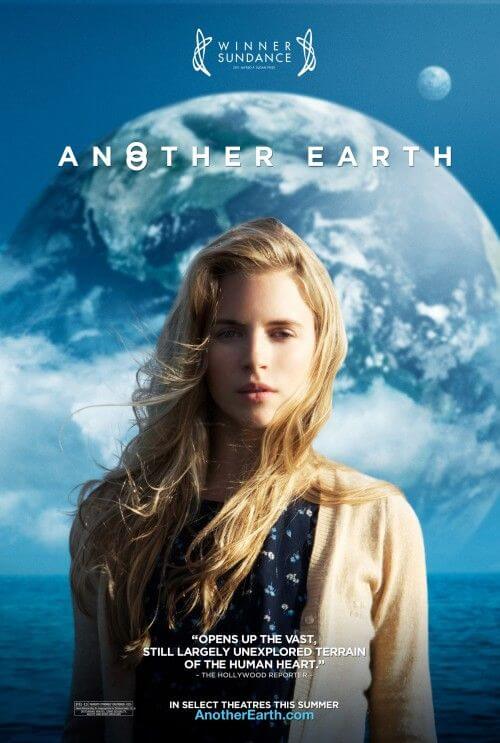

Another Earth is a fine example of what aspiring young filmmakers can do with a relatively small sum of money, minor equipment, and lofty—though not always cohesive—ambitions. Made for an estimated $150,000, the small-scale production, underlit and grainily shot with a handheld digital camera, features one or two grandiose ideas courtesy of background special FX tacked onto the foreground’s cumbersome narrative. It’s an interplanetary affair, an intimate indie drama beset by vast spatial implications that never quite make their mark on the earthly story. Having debuted at 2011’s Sundance Film Festival, it was a much-lauded release, bringing all eyes to the first-time director and co-writer Mike Cahill (not to be confused with the same-name helmer of King of California) and his star, co-writer and producer Brit Marling. But of several 2011 films in which a human drama plays out against cosmic happenings, this one offers the least in terms of feeling or stunning visuals.

The film opens with the news that scientists have discovered a “duplicate Earth” in orbit around the Sun. That night, future astrophysicist Rhoda (Marling) celebrates her acceptance to MIT by driving home drunk. As she stares out the window up at the blue speck known as “Earth 2”, she crashes into another car, killing the woman and child passengers, but leaving the husband/father alive and in a coma. Four years later, after former Yale music professor John Burroughs (William Mapother) comes out of his coma, Rhoda is released from jail. Plagued by her guilt, she resolves to apologize to him face-to-face, but when she arrives on his doorstep she can’t follow through. Instead, she passes herself off as a cleaning lady and offers to clean his home, which is littered with empty booze bottles and general dismay. Rhoda, who also now works as a janitor at the local high school, cleans up and helps him get his life back together after the tragedy. All the while, she never knows if she’s doing this for herself or for him.

Meanwhile, scientists, overheard on radio shows and news broadcasts, talk about Earth 2, which is no longer a blue speck but a massive orb in the sky. Reports explain that it’s a carbon copy of our planet, a parallel world complete with a mirror version of everyone on our Earth, leading many to wonder what’s different about their doppelganger—what choices have our doubles made that are different than our own? This becomes particularly important for Rhoda, who wonders if Earth 2’s version of herself made the same mistakes. Perhaps John’s family is still alive over there. To find out, she enters an essay contest with a company called United Space Adventures to be among the first to visit Earth 2, as apparently widespread radio communication with the planet is shoddy at best. But by the time she wins the contest, she’s started a compulsory affair with John and no longer knows if she’s ready to leave.

Here is one of two films from 2011 in which the sudden appearance of a random planet in orbit symbolizes the inner turmoil of the protagonist, the other being Lars von Trier’s Melancholia. Neither film fully integrates this high-concept device into its story, leaving any believable scientific factoids on the wayside as a devastating, highly metaphoric drama plays out. Both film’s narratives could exist on their own terms without the need for their sci-fi flourishes, and in fact, the addition of their cosmic anomalies only distracts from each film’s story—because as much as we’re interested in the drama surrounding the protagonist, we also want to know more about the planet. As a result, neither film works, not completely.

Cahill puts forth a more consistent, affecting story, whereas von Trier’s tale remains allegorical and fragmented. Cahill’s visual approach is muddy and gray and unpleasant to watch; von Trier’s is polished and elegant, and rather impressive. Both films feature their female protagonist disrobing at night before the moonlight-like glow of the rogue planet. Also, both feature great performances by their leading ladies. But as much talent as Marling displays, her portrayal is undone by a film barely exploring the implications of a “broken mirror” universe. Theoretical physics-driven debates are expounded throughout the course of the film, but nothing’s done with them until the open-ended last shot—one that’s bound to upset viewers with its abruptness.

In its most basic terms, great science fiction hinges on the idea of incorporating a scientific notion into a narrative and using that narrative to explore said notion. Another Earth uses science—and vaguely described theories at that—as a springboard and doesn’t look back. The story never gets beyond What if? Whereas authors like Philip K. Dick (Minority Report) investigate sci-fi theories to the fullest, Cahill and Marling have constructed a drama around a neat idea, but chose sappiness over intrigue. After all, could there be a more transparent, sappy metaphor than a guilt-ridden protagonist who cleans in order to cleanse her conscience? The film spoils a compelling idea by treating the subject like a hypothetical, instead of a device that brings the protagonist’s world crashing down.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review