Anora

By Brian Eggert |

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on November 5, 2024.)

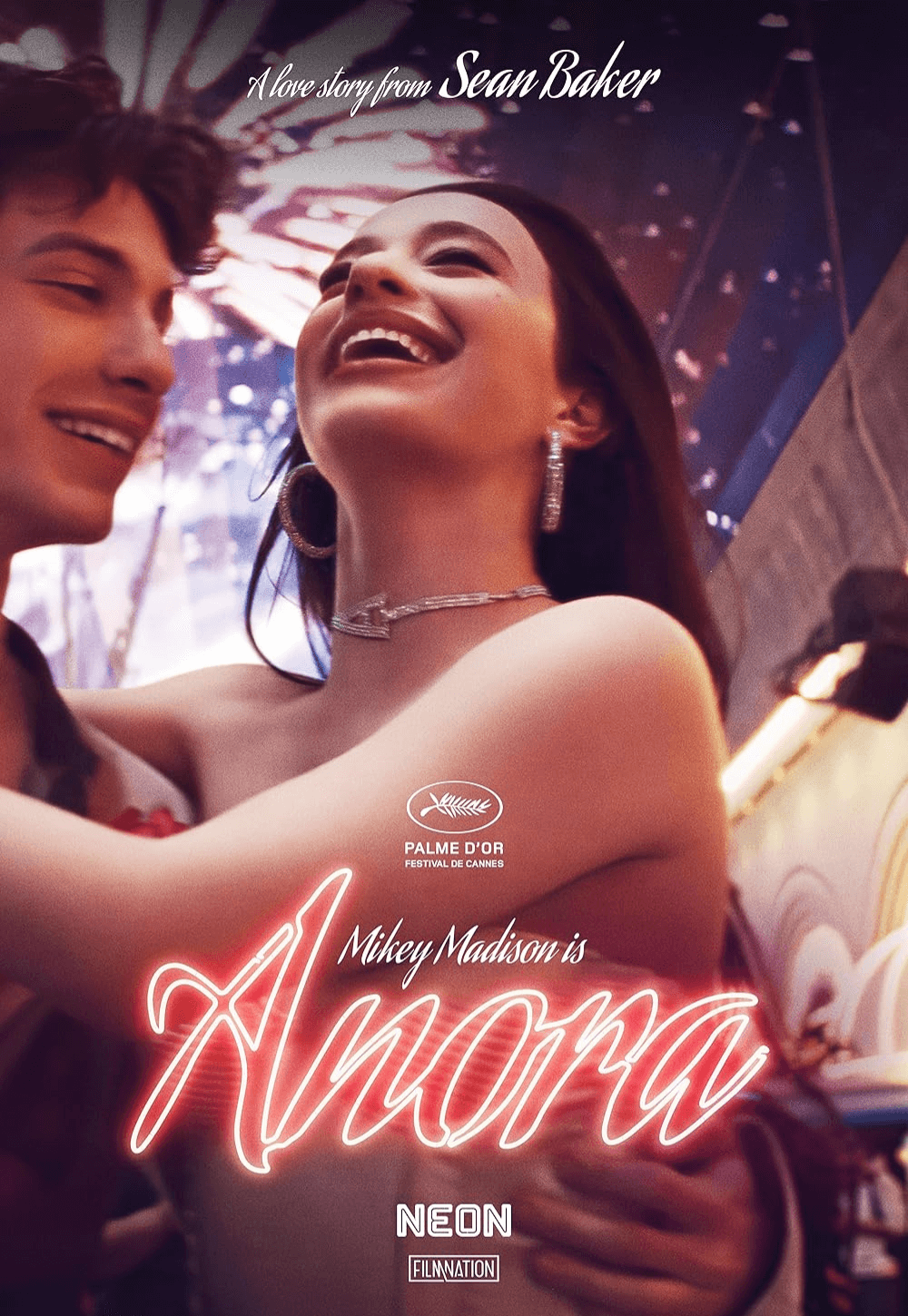

Sean Baker once again explores the false promises of the American Dream in Anora, an ersatz Cinderella story marked by a sobering dose of reality. This sexed-up anti-fairy tale follows Ani, a Brooklyn-based exotic dancer who can be tempted by the right client at her club, Headquarters, to dabble in sex work. Because she’s Russian-American and understands the language, she’s introduced to Ivan, a spoiled Russian man-boy with untold riches thanks to his mysteriously influential father. They fall for each other and live happily ever after, which is not at all what happens. Baker once again delves into his characters’ chaotic, shrill lives, which range from abrasive and hollow to genuine and warmhearted. Those last two qualities don’t factor much until the final stretch of the writer-director’s Palme d’Or-winning comedy, an engaging but caustic experience many have celebrated. My reaction is far from rhapsodic. Though I appreciate Baker’s continued interest in showcasing characters marginalized by society, and I admit it’s impossible to deny the immediacy with which Baker directs, Anora didn’t cast the same spell on me that it has on so many others.

Baker’s subjects tend to come from low-income and working-class sectors. Take Willem Dafoe in Baker’s lauded 2017 effort, The Florida Project, playing the manager of a crummy motel on the margins of Orlando. But Baker also delights in challenging his audience to empathize with his outsiders. In his last film, Red Rocket, Simon Rex plays a sleazy ex-porn star who’s always got a story or an excuse and a plan he’s trying to hatch. Baker is terrific at placing us inside his characters’ specific worlds and making us feel like a part of the moment, giving us a slice of humanity we might not be exposed to otherwise. He’s also one of the first significant filmmakers to use an iPhone to shoot a feature, with 2015’s Tangerine, probably his best film in its unpolished, immersive energy and form-follows-function execution. His characteristic zippy momentum and breakneck pacing entrance us in Anora, aided by his use of 35mm celluloid and energized handheld camerawork, which occasionally finds small moments of great beauty.

Serving as the writer, producer, director, editor, and even credited caster, Baker has a hand in every aspect of his production. As usual, he’s excellent at finding and showcasing the untapped depth of his performers. For Anora, he places Mikey Madison in the lead role. Some will likely recognize her as one of the Manson Family psychos in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019) or one of the killers from Scream (2022). Madison brings that same volatile energy to Ani, 23, who enters into a transactional relationship with the 21-year-old Ivan (Mark Eydelshteyn), who goes by Vanya. At first, he pays her for private dances and sexual rendezvous. Then he suggests a week-long fling, and she agrees, settling on a price tag of $15K. She confesses that she would have taken $10K; he admits that he would have paid up to $30K. Their quid pro quo may recall the setup of Pretty Woman (1990) on the surface, but Baker has more on his mind than creating another cliché fantasy. This is despite Vanya proposing to her during an impulsive trip to Las Vegas, where they’re fueled by drugs, alcohol, and bad sex. They seal their supposed love with a marriage certificate at a wedding chapel.

Anora has more in common with Nights of Cabiria (1957), Federico Fellini’s heartbreaking Italian drama where Giulietta Masina yearns to be loved but finds her would-be lovers are exploitative and deceptive. As it turns out, Vanya’s parents in Russia don’t approve of the union, and they order their US-based fixer, Toros (Karren Karagulian), to get the marriage annulled. Toros assigns two thugs, Garnick (Vache Tovmasyan) and Igor (Yura Borisov, the film’s secret weapon, from 2021’s Compartment No. 6), to find Vanya at his father’s mansion. The chaotic scene finds Vanya splitting on foot, while Ani is left with the goon squad. She fights with understandably harsh words and slapstick violence until, eventually, Toros and company force her to join in a race to locate her new husband. She learns along the way what an immature child he is—though nothing about his behavior up to this point suggests a mature adult. Maybe Vanya represented a method of escape from Ani’s work as an erotic dancer. Then again, this film takes a nonjudgmental approach to Ani’s profession, neither glamorizing nor condemning it. Instead, maybe he seemed like a fairy tale prince, offering to give her a new, luxurious life. It’s difficult to tell since Baker doesn’t explore Ani’s inner life.

Much of Anora unfolds in two modes. The first mode is an almost nonstop procession of partying, stripping, and sex, with occasional stops to watch Vanya playing video games while Ani clings to him. The second part involves Toros and company searching Vanya’s hangouts for any sign of him, from candy shops and restaurants to various nightspots. With the film running nearly two and a half hours, these scenes feel tiresome and repetitive, though shot by cinematographer Drew Daniels with urgency and authenticity. These modes are each effective in what they aim to evoke; there are simply too many of them for my liking. Capturing various spots in Brighton Beach, Baker finds visual splendor in the chaos—a shot of a sunset over the boardwalk is a stunner. But these are crammed between a nonstop procession of coarse insults, bickering, and attitude that lost their intentional humor and became grating after a while. At the same time, the plot machinations sideline Baker’s faint interest in his characters’ personalities, histories, or ambitions. The plot is involving and entertaining, but even as I felt empathy for Ani and later Igor, I didn’t feel like I really knew them by the end.

Like most of Baker’s works, Anora is unquestionably a well-made film. But I often feel removed from his subjects because he tends to emphasize moments over the emotional realities of his characters. He’s a great observer of heated situations and capable of imbuing unlikely types and messy situations with humor, charm, and energy to spare. However, he regularly reserves only a minor instant, usually at the finale, where his protagonist removes their mask and allows themselves to be seen. While this can and has led to overwhelming emotional responses to his films, it’s a tactic that, upon reflection, makes the rest of each film feel like it was spinning its wheels and not really getting anywhere. Maybe that’s why one of his most affecting works, The Florida Project, centers on children who have not yet learned to wear masks. For Anora, the emotional wallop at the end is terrifically acted by Madison, whose character is otherwise difficult to enjoy spending time with. But her rare instance of vulnerability arrives after several exhausting, tedious, and monotonous episodes that might make getting through them a chore.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review