Anonymous

By Brian Eggert |

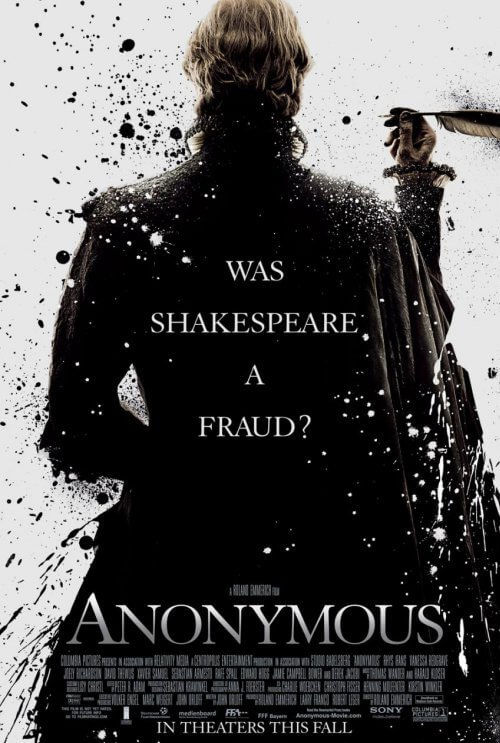

For Anonymous, director Roland Emmerich has set aside destroying the world again and instead engaged himself in a scholarly pursuit; which is to say, scholarly for a filmmaker whose films include Independence Day and 2012. Emmerich and screenwriter John Orloff render the Elizabethan equivalent of Oliver Stone’s JFK and present a popular conspiracy theory that questions whether or not William Shakespeare actually authored his body of work. In doing so, the filmmakers embrace a whole slew of half-cocked notions that fuel an entertaining period melodrama (plump with schemes, revenge, forbidden love, and incest). Costumes by Lisy Christl and restrained CGI scenery deliver an elegant, if stylized, interpretation of the era, but don’t expect subtlety from Emmerich just because the planet isn’t hanging in the balance. He pours on hammy performances and plenty of intrigue, making the result costumed trash of the most well-meaning variety.

A range of historians argues that, among others, either Francis Bacon, William Stanley (6th Earl of Derby), Christopher Marlowe, or Queen Elizabeth herself most likely wrote the work attributed to Shakespeare. Anybody, it seems, except the Bard. Of course, there’s plenty of evidence for and against each hypothesis. At the top of the “against” category stands the actor-turned-playwright’s humble origins, his lack of aristocratic education and experience at court, and his uncharacteristic end as a banker and grain merchant. Not to mention the lack of physical evidence; not one original manuscript in Shakespeare’s handwriting survives. With this in mind, Emmerich’s film opens on modern-day Broadway, where a production called “Anonymous” features Derek Jacobi preaching the doctrine of Oxfordianism—the rather compelling theory that Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, wrote Shakespeare’s entire opus.

From here, Emmerich effectively transitions into 16th century England, where Edward de Vere (Rhys Ifans) cannot publish his plays because of his status, as the Puritans believe that poetry and plays equate to worshiping false idols. To command the mobs attending plays at The Globe Theater, Edward plans to hand his writings over to a known playwright, Ben Jonson (Sebastian Armesto), who will take credit and receive Edward’s glory, and in effect, communicate Edward’s hidden messages to the masses. Ultimately, Edward wants the Earl of Essex (Sebastian Reid) to replace the aging Elizabeth (Vanessa Redgrave) as England’s ruler after her death, and not the eventual King James as the slippery courtiers William Cecil (David Thewlis) and his hunchback son Robert (Edward Hogg) would have. But before Jonson can take credit, illiterate Globe actor William Shakespeare (Rafe Spall) undercuts him to steal authorship of Henry V and each of Edward’s subsequent plays, all the while boasting of his genius and bowing with false humility before his audience like he’s accepting an Oscar. During post-play “thank you” speeches, Shakespeare ineloquently stumbles over words, laying on heavy he’s-a-dope shtick.

Meanwhile, the film’s nonlinear structure leaps back and forth through history, preventing us from having much of an emotional connection to the proceedings. Orloff’s script begins five years after the film’s main events when Jonson is being interrogated by the younger Cecil to obtain original copies of the plays to be destroyed. We then leap to twenty years before, during which time a young Edward (played by Jamie Campbell Bower) and Elizabeth (overacted by Joely Richardson, Redgrave’s daughter) have an affair and conceive an illegitimate child, and the elder Cecil plots to banish Edward. As a result, as watchers of this film, we’re seeing a stage play that relates a story told from Jonson’s point of view, using a series of flashbacks-within-flashbacks. The structure proves inconsistent at times, even if Jacobi’s stirring bookend appearances begin and end the film on high notes.

Emmerich glosses over the plays themselves, offering a montage of sorts that touches on all of the best-known lines like “To be or not to be” or “Now is the winter of our discontent” and so forth. He effectively places the plays in a historical context, however, so viewers familiar with these works (a percentage of the moviegoing audience that I fear is very small) have a nice idea of why the plays were so relevant in their day. Much of this is to posture Oxfordian theories, which have an adequate platform here. Touching on the plays’ broad strokes also establishes Emmerich and Orloff’s intentions to make Anonymous something of a Shakespearian tragedy itself, as they set up Edward’s lofty aspirations and watch as they disintegrate. Although, the filmmakers succeeded more in realizing an undergraduate-level historical study with questionable references and soap opera embellishments—albeit in the most entertaining way possible.

To be sure, at times, the film is a pleasure to watch. Ifans proves surprisingly charismatic as Edward, his upturned eyes and heavy brow placing gravitas behind his silly bleach-blond hair (he also incites involuntary laughter when he laments about the voices in his head and the need to set them to paper). Too, Redgrave gives much dimension to her version of Elizabeth, which isn’t as charming or compelling as versions played by Judi Dench or Cate Blanchett. All around, the supporting players are strong—save for the exceptions of Bower, Hogg, and Spall, each performance more exaggerated than the last. Viewers will be more impressed with how Emmerich uses remarkable soundstages to create many of his sets, including the striking theater set pieces, and then augments larger-scope photography with period-creating CGI to give his production an overall polish. The production isn’t quite as painstakingly accurate as Elizabeth nor quite as emotionally dynamic as Shakespeare in Love, but there’s a strong sense of atmosphere and mood throughout.

Few will walk away from Anonymous convinced of its historical legitimacy, yet interests will be piqued, perhaps inspiring some to read up on the subject from more credible sources. Still, there’s no denying that Anonymous is Emmerich’s best film, a work that doesn’t rely on explosions and wow effects to enrapture its audience, yet doesn’t preach too seriously on its otherwise academic subject. Sure, there are moments of over-the-top acting and plotting; no one’s applauding Emmerich for his refinement here. But it’s an accessible and rather scandal-driven costume drama that’s interesting and visually arresting, even if it’s also imperfect and structurally a mess. That Emmerich was compelled to step away from his usual no-brainer blockbusters to realize something truly different in his oeuvre, and then succeeded, shows that there’s an evident talent behind the camera. Now, if only he continued to make passion projects like these instead of mindless disaster movies.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review