Annihilation

By Brian Eggert |

Fission occurs when cells replicate and then divide. The process involves a single cell that splits itself in two, thereby negating its original form in service of two distinct cells. Growth and healing rely on this otherwise violent act, which signals Nature’s impulse to self-destruct in order to create. It’s a theme that prevails throughout Annihilation, writer-director Alex Garland’s film of Jeff VanderMeer’s 2014 novel. A microscopic view of cell division recurs as the film’s central motif, lovingly integrated into Garland’s visual and narrative choices. But the horrible beauty of the Kantian sublime dominates this intelligent, aesthetically wondrous production, leaving the viewer with much to contemplate about our human biases toward the essence of creation. (After all, while the rapid growth of, say, bacteria in the human body has been described as a disease, it’s a time of prosperity in the microcosm of the bacterial world.) Conceptual as such ideas may be, Garland never forgets to mirror them with human drama. Indeed, within Annihilation‘s visceral yet thoughtful science-fiction context, his characters undergo fission to either self-destruct or become something new.

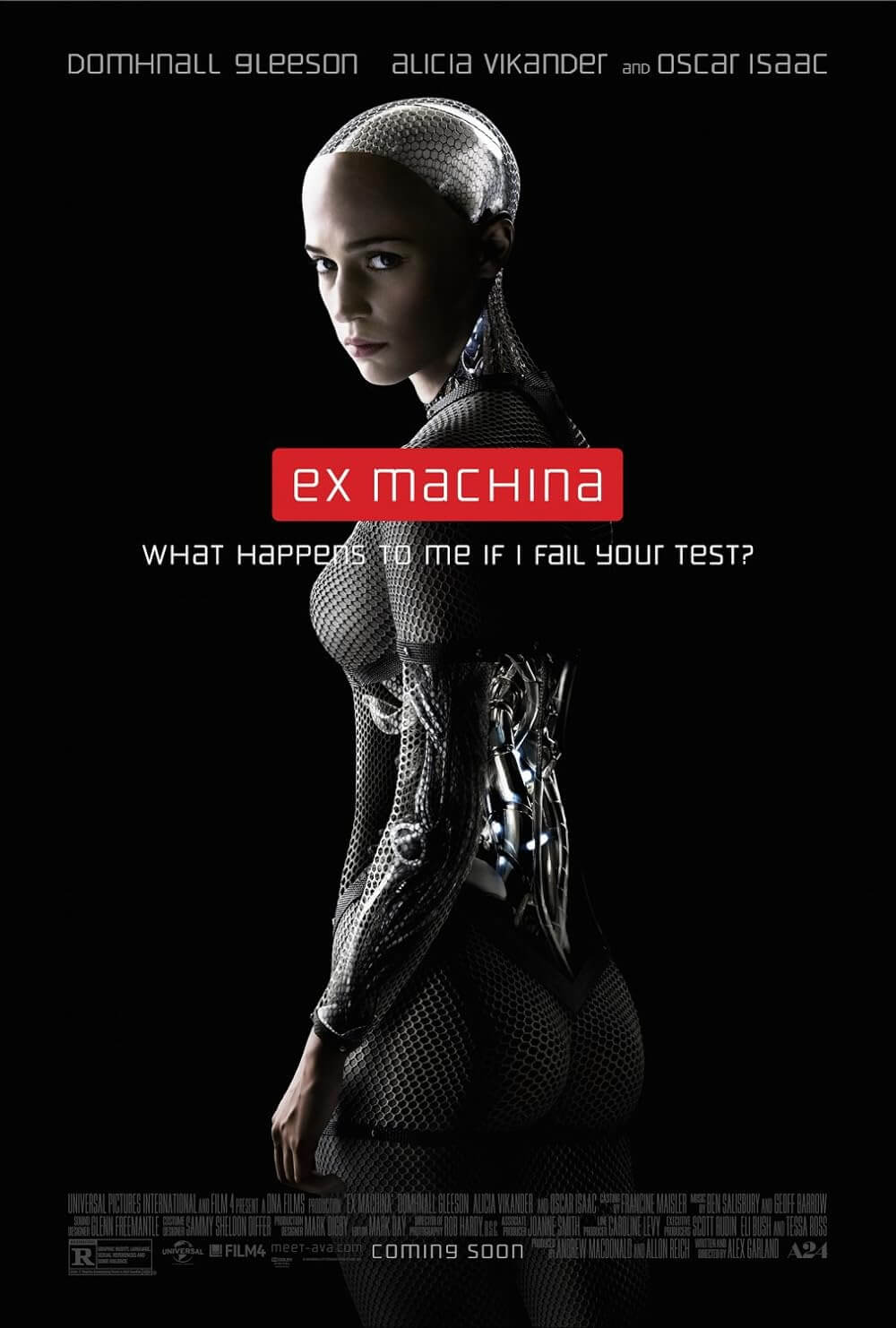

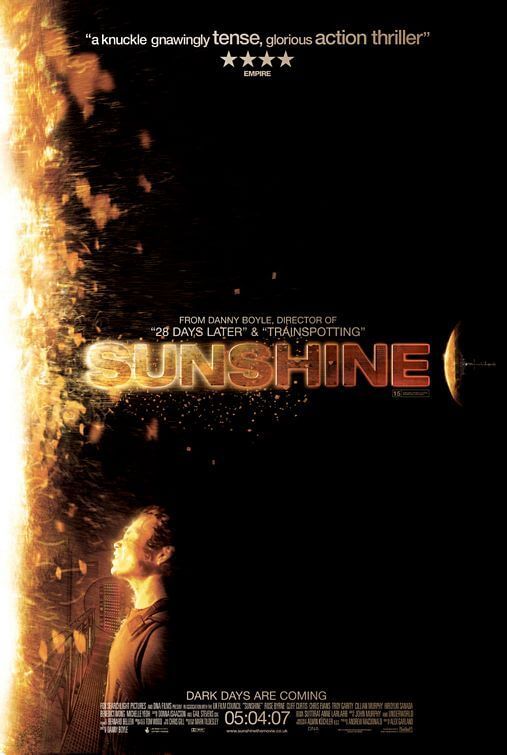

Garland is ideally suited to adapt VanderMeer’s book. During his early career as a novelist and screenwriter, he collaborated with British filmmaker Danny Boyle (and others) on several original screenplays that represent some of the best genre material in the last two decades. After a disappointing adaptation of his book The Beach in 2000, Garland worked with Boyle on the first true zombie reinvention of the twenty-first century, 28 Days Later… (2002), followed by the underseen space odyssey Sunshine (2007). He later wrote the screenplays for Never Let Me Go (2010) and the cult favorite Dredd (2012), proving his ability to alternate between substantive genre work or a severe comic book world. He finally directed his feature debut Ex Machina in 2014, earning a deserved Academy Award nomination for his screenplay, while his film won the Oscar for best visual effects. In each effort, Garland the writer incorporates powerful human exchanges into a complex science-fiction scenario. His ability to intertwine an accessible, emotional narrative with ideas explored by some of the genre’s headiest practitioners puts him in the same arena as Philip K. Dick.

For Annihilation, Garland chose aspects from each entry in VanderMeer’s “Southern Reach Trilogy” to synthesize the author’s complex, sometimes abstract conclusions for the screen. To borrow a term from the film, Garland refracts the novel rather than provide a faithful adaptation, bending the material from one medium into another to fit the requirements of cinema, as the best book-to-film adaptations do. It opens with a shot of a meteorite—that most efficient delivery system of apocalyptic horrors from The Day Of The Triffids to The Blob—falling to Earth and striking a lighthouse on the southeast coast of the United States. Mutated plants and animals have spread from this central location, surrounded by a living wall called “the Shimmer.” After this early scene, a framing device gives the film its structure: Lena (Natalie Portman, in a wonderful, mature performance) has been quarantined inside some manner of government facility, where she’s debriefed by an official in a hazmat suit (Benedict Wong). Her mission was supposed to last for 2 weeks. She didn’t return for 4 months. Where has she been? What was it like inside? She experienced lifeforms inside. What were they like? She answers each of these questions with a distant “I don’t know,” struggling to remember what happened to her fellow scientists.

Before her experiences in the Shimmer, Lena was an academic teaching cellular biology at Johns Hopkins and married to Kane (Oscar Isaac), whom she met during her 7 years in the army. They shared a playful romance, seen in endearing flashbacks of humor and affection, though Kane’s series of top-secret missions to undisclosed locations, each for an indeterminate amount of time, led to Lena’s unfaithfulness. Kane eventually disappeared on such a mission into the Shimmer, and that was a year ago. She’s since tried to move beyond her guilt and mourning. Did she drive him to accept an assignment from which he knew he would not return? But just then, Kane returns home without warning, a silent shell who replies to all questions with the same empty response: he answers “I don’t know,” just as Lena will do, as if he’s never considered where he’s been and what he’s seen. All at once, his organs begin to fail and he coughs up blood. Lena and Kane are transported to a facility called Area X. She meets a psychologist, Dr. Ventress (Jennifer Jason Leigh), who explains the Shimmer and its ever-expanding threat. Multiple teams of drones, animals, and soldiers have gone inside. None have returned, except Kane. The prevailing theories: it’s a religious event, an extraterrestrial visit, or an inter-dimensional rift—or perhaps some combination of the three.

Lena volunteers herself to go inside, driven by guilt and the need to find a cure for her husband. The all-female team consists of experts, each with a character flaw that makes them expendable (an essential characteristic for a suicide mission). Dr. Ventress leads a group that includes Sheppard (Tuva Novotny), an anthropologist who lost a child; Anya (Gina Rodriguez), a paramedic and addict; and Josie (Tessa Thompson), a physicist with a tendency for self-mutilation. Ventress, we notice, is an emotional cipher, if rather sad and nervous. As their team approaches the boundary of the Shimmer, Garland allows his audience a moment of awe. We cannot help but feel transfixed by a moving, luminescent pane that seems to be coated in a gel of prismatic colors. Once inside, the team loses any memory of the past several days, a detail that remains frustratingly unexplained. But it’s easy to become distracted by the surrounding tropical ecosystem. Flora grows wildly out of control in ways that make no sense to the laws of Nature. Lena observes a vine on which multiple flower species spring from the same stem; later, they meet an albino alligator with teeth growing in concentric rows like a shark’s. Plant and animal species have been torn apart and reassembled in fascinating if entirely unnerving ways.

Garland and cinematographer Rob Hardy fuse Annihilation‘s themes into their visual motifs without making the integration overt; and yet, wherever you look, the story, subtext, and form maintain an intricate balance. Consider how Ventress just wants answers before she’s consumed by cancer, a disease that represents death by uncontrolled cell growth. Or how Lena and Kane’s relationship recalls two cells coming together and then being torn apart. After Josie realizes the Shimmer “refracts” not only radio waves and light but also DNA, the visuals have even further meaning. Garland captures his theme in simple but evocative shots, such as an early one of Lena and Kane’s hands touching behind a glass of water, the image bent by the cylindrical shape. The entire production, realized by designer Mark Digby and overseen by visual FX supervisor Andrew Whitehurst, contains a spectrum of colors that have been curved and deflected from somewhere else. Inside the Shimmer, Lena’s team walks through an omnipresent rainbow mist, while Hardy uses lens flares that spray rich pinks and purples across the screen.

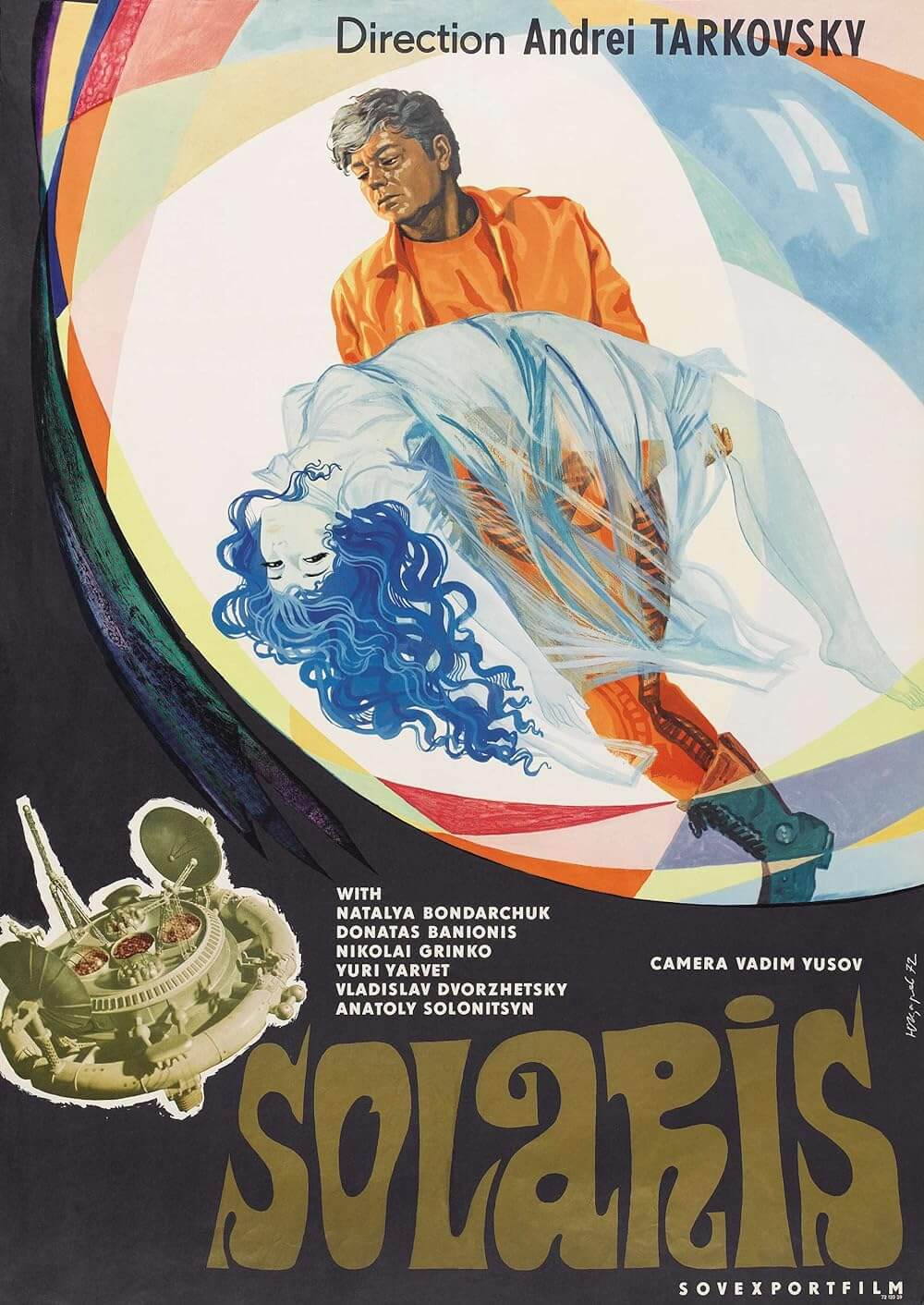

Other choices are less obvious, such as the use of the song “Helplessly Hoping” to encompass Lena and Kane’s relationship with its lyrics: “They are one person, they are two alone, they are three together, they are for each other.” Doubtful Crosby, Stills & Nash meant their 1969 song as a metaphor for cellular fission, but Garland’s choice is inspired. Elsewhere, the director adopts a more accessible use of memory-images and weighted considerations of lush, natural landscapes—however otherworldly—and he echoes similar concerns in Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972), or even Soderbergh’s remake. Similarly, the apocalyptic setting and hypnotic search for answers inside the Shimmer bring to mind Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and even Garland’s own work. When Josie finds herself entranced by the unhinged interspecies plant growth, neither wanting to escape nor confront it, she reminded me of the character in Sunshine who became addicted to staring at the Sun. “Total light envelops you,” he explains. But being consumed by light itself was an addiction that left him burned and covered in peeling skin, an act of self-destruction and fulfillment.

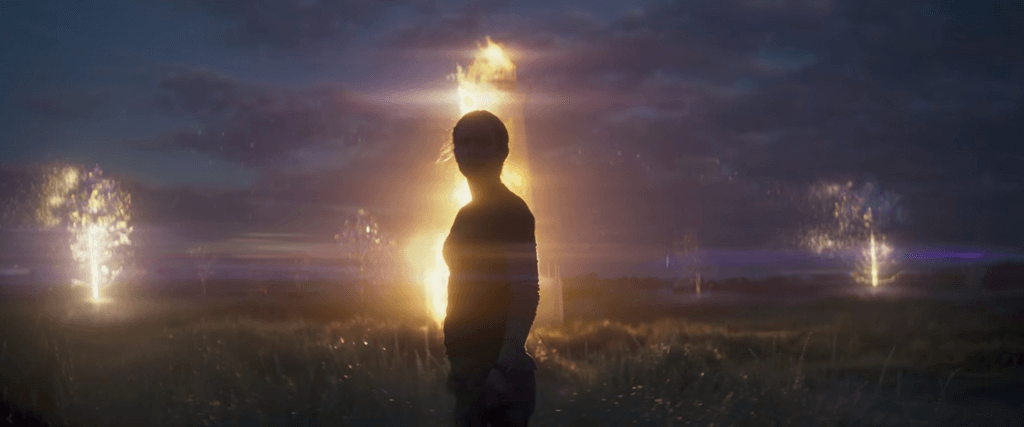

Whether the Shimmer beautifies Nature or corrupts it, the effect creates a true sense of the sublime, sometimes horrific and sometimes uncannily beautiful. Each member of their team has already begun to change on a cellular level. Many of them realize they will not be able to leave the Shimmer as the same person, quite literally. When the group sets up camp at an abandoned military base, they find a terrifying video from the last mission, Kane’s team, followed by the fungal result of a former soldier transformed from the inside-out by genetic refraction. Anya feels as though she’s losing her mind because when she looks at her hands, they seem to be changing right in front of her. Later, Lena and company are hunted by a skull-faced bear that roars with the screams of its victims, having absorbed some part of its victim’s mind. Things get even stranger in the climax, as Lena reaches the lighthouse to find another video, except this one depicts Kane committing suicide, while Kane’s exact copy records the moment—presumably the same Kane-copy now dying in a government facility outside of the Shimmer. And then she meets the Shimmer’s black-oil humanoid composite, a creature that mirrors her every movement in an attempt to—what? Understand Lena? Digest and replace her? Perhaps she’s already been replaced. The inconspicuous appearance of Anya’s Ouroboros tattoo on Lena’s forearm certainly raises some questions.

Many of these ideas permeated VanderMeer’s trilogy, but Garland concentrates them in alternate ways that invent something new, while also preserving the novel’s original meaning. What Garland does best is transform the material into great filmmaking. His visuals are incredible and original, and I haven’t felt so moved or awestruck by science-fiction since Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin (2014). For every moment of visceral horror, there are several more whose sublimity both haunts and astounds. All of this says nothing of the incredible performances, Portman above all, and their ability to make the fantastical situation feel grounded in human emotion. And while Annihilation could be interpreted in a multitude of ways—a film about aliens, multiple dimensions, or a religious experience—there’s a sense of finality and completion in the end. But not enough to stop us from returning to Garland’s film in the years to come to anatomize its parts.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review