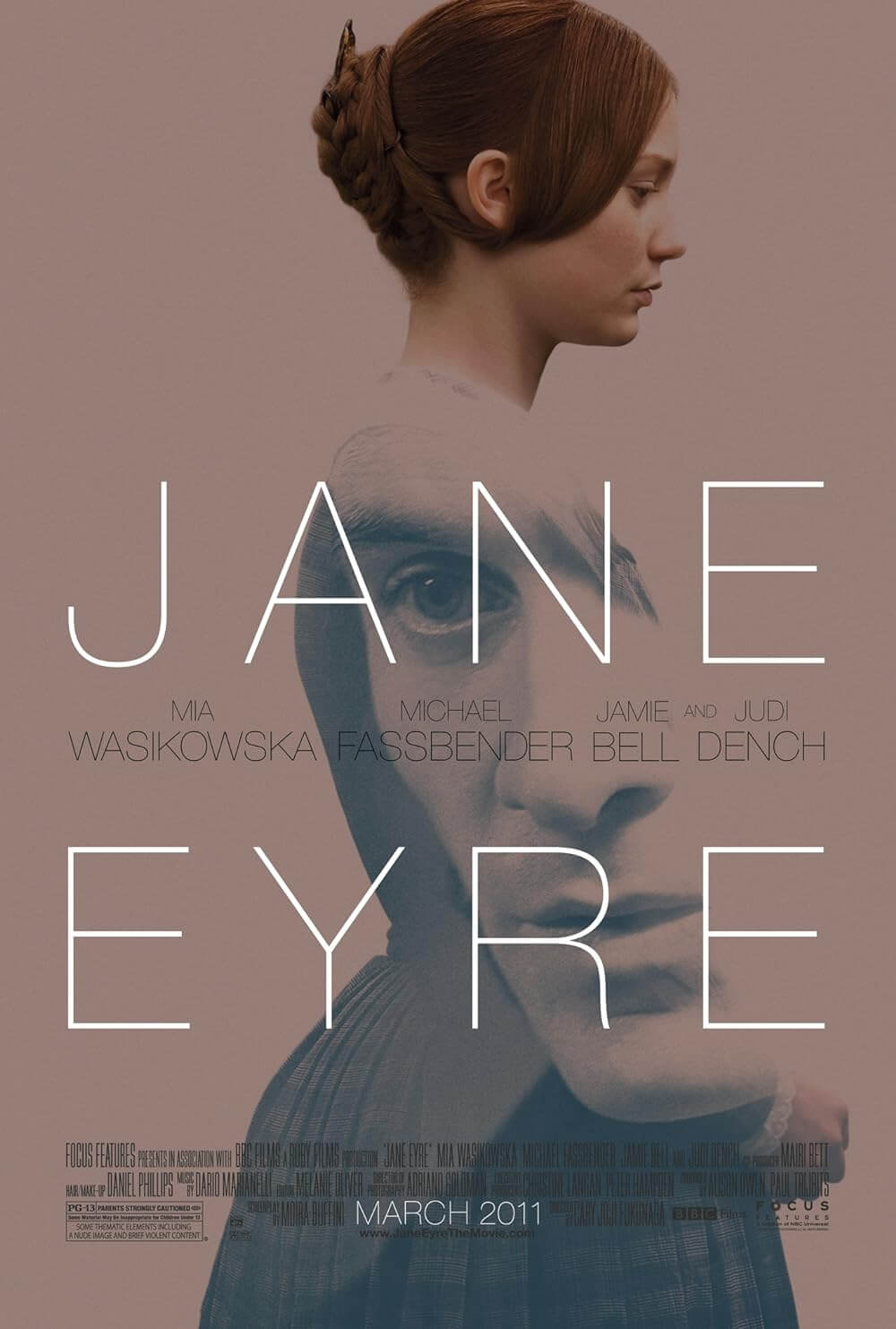

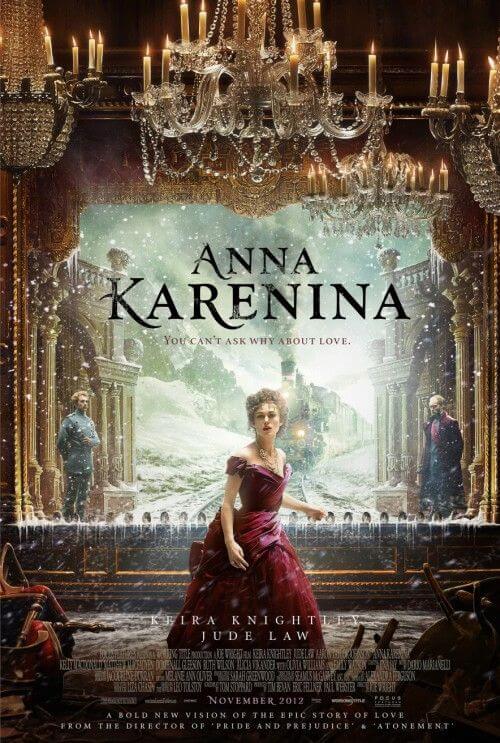

Anna Karenina

By Brian Eggert |

Anna Karenina is a cinematic tradition. Although a new filmic adaptation of Leo Tolstoy’s romantic tragedy tome arrives every few years, not a single one has bested the 1935 Warner Bros. version starring Greta Garbo, including the most recent from Bernard Rose in 1997, which featured Sophie Marceau and Sean Bean. For the latest adaptation, director Joe Wright incorporates an overwhelming degree of novelty flourishes to set his film apart from the surplus of other adaptations, and in turn Tolstoy’s work receives a unique treatment courtesy of this imaginative filmmaker and his screenwriter, playwright Tom Stoppard. Together, Wright and Stoppard compress their source by shrinking the scope into what becomes an inconsistent metaphoric theater setting, over-emphatically reminding the audience that “All the world’s a stage.” With a certain distance placed between the viewer and characters because of this interpretation, the film’s uniqueness among other such adaptations is offset by its own preoccupation with style and often overwrought symbolism.

Past adaptations have struggled to effectively reduce the text into a reasonable runtime without sacrificing essential characters and themes from Tolstoy’s 900-plus pages. For this, Stoppard must be commended. His screenplay touches on essential characters typically written out of past versions, while his treatment of the characters changes their usual function in interesting if unsuccessful ways. Anna (Kiera Knightley), the wife of respected government official Karenin (Jude Law), finds herself drawn into an affair with a Russian cavalry officer, Count Vronsky (Aaron Taylor-Johnson). Anna would divorce her staid husband for Vronsky but law and society’s rules prevent her from receiving any allowances from the cuckolded party; in fact, she will be completely stripped of status and financial backing if she leaves Karenin. Somehow, this Anna lacks the character’s glowing inner beauty and seems selfish; at the same time, the film represents Karenin as a quietly sympathetic, if impassionate and staid figure, while customarily, he’s villainous. Vronsky only seems seductive because other characters tell us so; the performance is one-note and unappealing, perhaps to emphasize Vronsky’s superficial choice in the finale.

Wright’s reteaming with Knightley (his Pride and Prejudice and Atonement star) for the third time marks their least successful outing, if only because Stoppard’s adaptation serves up Anna as a manic, occasionally cruel force. Here, she leaves her victimized husband and their innocent child and chooses a shallow lover in Vronsky for what feels like nothing more than lust. Not even Knightley’s powerful performance can make up for how the filmmakers have chosen to represent this usually warm character so enlightened by love and oppressed by her culture. Johnson’s shortage of personality in his role makes Anna’s choice even more questionable. Law’s restrained, two-timed husband role has more layers but remains devoid of the necessary antagonist traits. The supporting players give the best, most well-rounded performances. Also present is Matthew Macfadyen as Anna’s brother Oblonsky, whose wife (Kelly Macdonald), caught in a catch-22, is convinced by Anna to forgive her husband’s adulterous ways—not that she has any choice; despite being the wronged party, if she chooses to divorce Oblonsky, she would be left with nothing.

All the while, these characters move about on filmed stages, the action occurring behind the curtain, amid the rigging, and with actors sometimes moving set-pieces in an out of the frame. Elaborate choreography sends the actors moving in unison to emphasize the monotony of clerical work, while the flashy Vronsky and Oblonsky twirl into their seats on every occasion. Each character behaves as if participating in a ballet. Ropes, wires, and background matte paintings are intentionally visible, and the actors’ shuffling feet are distractingly audible as though Wright had resolved to film an actual play. In every detail, the metaphoric setting recalls expressive, over-the-top efforts from Baz Luhrmann (Moulin Rouge) and Julie Taymor (Titus), whose ostentatiousness can and often does distract from the dramatic pull of their material. Moreover, Wright also employs a number of other obvious visual metaphors beyond his central stage imagery. Whenever Anna and Vronsky make love, Wright fades to train wheels churning, as if their lovemaking drives Anna toward her fate. Anna also finds herself looking into fragmentary mirror reflections throughout the film, underlining her necessity for duality in Russian society. Each of the stated metaphors is repeatedly employed and feels overused and eventually redundant.

A stylistic counterpoint to Wright’s staging of Anna’s love triangle is how he handles the fledgling romance between Levin (Domhall Gleeson) and Kitty (Alicia Vikander). The former a mere farmer and the latter a would-be lady of circumstance, Kitty gives up her social life for true love. By comparison, these characters, often omitted from adaptations of Anna Karenina, share scenes at Levin’s farm, shot at actual locations in Russia. Since the honest farmer Levin remains outside of the stage-like world of high society, Wright represents his farm as natural and true. As a result, we see what an extravagant film Wright might’ve made had he chosen a more conventional approach and used real locations throughout. We also feel a jarring inconsistency when, after twenty minutes of staged scenes, the stage doors open on a vast snowy landscape, gorgeous scenery comparable to scenes in Doctor Zhivago. Of course, each time Wright returns to the impressive sets and costumes of his staged society world, his film’s metaphor is further ingrained, as we feel underwhelmed by the artificiality of social politics. Nevertheless, the visual symbolism abound doesn’t bring us closer to the narrative.

Other films have underscored their life-is-a-theater themes with subtle and more effective visual motifs. Consider the French classic Children of Paradise, which, in addition to being about a troupe of performers and artists, opens and closes with a curtain. Or consider how Terry Gilliam’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen suggests the entire film is a fantastical play by dissolving from a staged performance into the fantastical exploits of the titular hero. Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game offered a scene where the characters dress up and put on a play, while their devotion to “the game” makes them all performers in an ongoing exhibition of manners. In each case, the filmmaker’s implementation of the stage metaphor is restrained enough to get the point across, whereas Joe Wright and Tom Stoppard have determined to beat their audience over the head with similar symbolism in Anna Karenina. No matter how much impressive ornamentation on the costumes or detail in the whimsical set designs, this ambitious film’s emotional impact suffers from the production’s almost obsessive preoccupation with surfaces and its deficient attention to the power of the tragedy itself. While even skilled filmmakers would have trouble adapting Tolstoy’s novel in a straightforward form, Wright attempts a book-to-stage-to-film approach and, for the first time in his career, stretched his considerable talent thin.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review