Reader's Choice

Anatomy of a Fall

By Brian Eggert |

Anatomy of a Fall examines a complicated woman, her troubled marriage, and a mysterious death, all within a courtroom setting. Directed by Justine Triet, who co-wrote the screenplay with Arthur Harari, the film unfolds with an increasing awareness that everything we think we know about people is an assumption on our part, and we can never really be sure about people or why they behave the way they do. That’s a potentially unsatisfying ambiguity when applied to a standard courtroom drama, a genre that often relies on the absolutism of justice to craft its morality. But then, this is anything but a standard courtroom drama, despite appearances. Although Triet adheres to a typical formula, where a suspicious death reveals the spouse as the prime suspect, and the drama that follows attempts to ascertain whether the accused is guilty, her film has loftier questions about reality and perception. The filmmaker refuses to answer every question or explain every incongruous detail in the case. That can be maddening for audiences accustomed to seeing cinematic courtrooms as locations where all facts come to light. But the film’s lingering uncertainties are also what makes it most compelling.

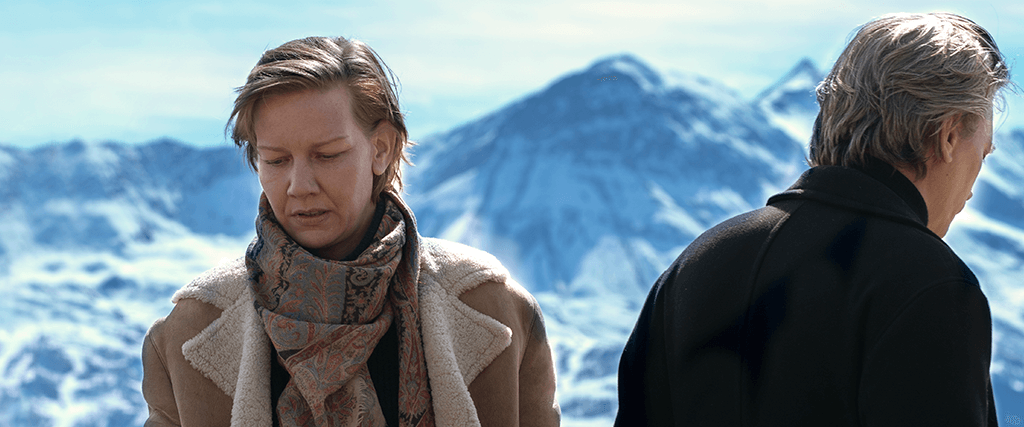

Sandra Hüller plays a successful author, Sandra Voyter, who lives in an isolated home in the French Alps. A woman out of place, she originates from Germany, lives with her French husband, Samuel (Samuel Theis), and they meet somewhere in the middle by speaking English. When a young female student comes to interview her, Samuel blasts an instrumental version of 50 Cent’s “P.I.M.P.” on repeat, creating an awkward scene that prompts Sandra to end the interview and the student to leave. Later, when their partially blind son, Daniel (Milo Machado-Graner, outstanding), returns from a walk with his guide dog Snoop, the boy finds Samuel’s body on the ground outside. It seems as though Samuel fell from the attic window where he was conducting repairs. But upon closer inspection, the authorities question some blood splatter and ultimately indict Sandra on suspicion of murder. When the case reaches trial a year later, Sandra faces intense scrutiny. Her defense attorney and friend Vincent (Swann Arlaud) supports her, but the fiery prosecutor (Antoine Reinartz) intends to question every facet of her life, marriage, and even artistic output.

This is the first of Triet’s body of work—including Age of Panic (2013), In Bed with Victoria (2016), and Sibyl (2019)—to break through to an international audience in a major way. After winning the Palme d’Or at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, and its subsequent acquisition by Neon for stateside distribution, the film arrives with questions about the ins and outs of French courts. The rather conversational dynamic between the judge (Anne Rotger), attorneys, witnesses, and accused throughout seems willing to interpret art as much as people, leading to a fascinating moment when the prosecutor reads from Sandra’s fiction to propose how her creative output might be a reflection of her reality. Elsewhere, Samuel’s psychiatrist gives one-sided evidence about their marriage, and Samuel’s choice of a “misogynist” 50 Cent song provides another interpretive window. Indeed, for much of the legal proceedings, the prosecution’s case seems rooted in presumptions and suspicions more than facts. But if the case hangs on a flimsy set of perceived motivations and physical evidence, it nonetheless supplies a platform to ask questions about how we define reality. The theme is not-so-subtly established when, in the first scene, the student (Camille Rutherford) who interviews Sandra observes her use of reality in her fiction, and she questions whether the author’s goal is to ask her readers to distinguish between them.

As the court case continues, Triet embraces the notion that we can never really know someone or what happened, and sometimes, as Daniel observes at one point, “You have to invent your belief.” In other words, in the face of uncertainty, you make a choice because that’s easier than accepting the unknown. Watching the film, you get the sense that Triet wants to put social media and cancel culture on trial, but also to question how the predominance of true-crime fiction has shaped our preconceptions. Perhaps society has seen one too many murder documentaries or serial killer limited series for its own good. To be sure, this is a film critical of how we choose to believe the worst in people because it’s more exciting that way. It’s a better story, and certainly more entertaining. When someone is accused of something, they’re practically convicted in our minds because of the accusation, and they remain guilty even if they are acquitted. But things are not always what they seem, and people’s motivations are seldom open-and-shut cases.

As the court case continues, Triet embraces the notion that we can never really know someone or what happened, and sometimes, as Daniel observes at one point, “You have to invent your belief.” In other words, in the face of uncertainty, you make a choice because that’s easier than accepting the unknown. Watching the film, you get the sense that Triet wants to put social media and cancel culture on trial, but also to question how the predominance of true-crime fiction has shaped our preconceptions. Perhaps society has seen one too many murder documentaries or serial killer limited series for its own good. To be sure, this is a film critical of how we choose to believe the worst in people because it’s more exciting that way. It’s a better story, and certainly more entertaining. When someone is accused of something, they’re practically convicted in our minds because of the accusation, and they remain guilty even if they are acquitted. But things are not always what they seem, and people’s motivations are seldom open-and-shut cases.

Triet acknowledges that people and the events that occur between them operate in a gray zone, and our systems are rarely adequate to process anything outside of black-and-white absolutes. And so, maybe it’s intentional that, working with cinematographer Simon Beaufils, Triet’s visual approach offers a range of techniques that never quite come together into a coherent or intentional aesthetic, except perhaps to acknowledge that the world consists of many perspectives. The camera sometimes feels like an objective observer, sharply moving during Daniel’s testimony to frame him in between attorneys. At other times, the camera is a spy, handheld and digital, watching from a really there position. Elsewhere still, we see projections of what happened from within the heads of various witnesses or low angles from the dog’s point of view. And while this employment of various techniques and perspectives can feel random or scattershot at times, they might, when considered on the whole, indicate that there’s no single source of truth in Anatomy of a Fall. Instead, it’s about the various ways people can see and interpret any situation.

Triet is a great director of actors and works with them to find the naturalism in each performance. Having studied documentary filmmakers such as Frederick Wiseman, she told Film Comment that she would attend actual trials to incorporate what she learned from them into her film—including a real-life case in which a lawyer used an author’s fiction against him. But she also carefully shapes performances to feel layered and authentic. Best known from Toni Erdmann (2016), Hüller’s performance is brilliant, offering a woman who can seem cold, harsh, and unforgiving, but she can also express motherly warmth. Another great performance belongs to the Border Collie named Messi, playing Snoop, who won the coveted Palm Dog prize at Cannes. Though, the production’s treatment of the animal actor looks questionable. For one scene where Snoop consumes some aspirin, the filmmakers clearly drugged the animal to achieve a doped-up look, which has some ethical implications that took me out of the film for a scene or two. Even so, Messi gives a compelling performance, and he’s clearly a good boy.

Anatomy of a Fall is a probing and fascinating study of humanity’s multifacetedness and its tendency to judge far too quickly. Even the title is clever in its allusion, which makes moviegoers think of Otto Preminger’s 1959 courtroom drama Anatomy of a Murder, a film in which a murder unquestionably takes place. By the title’s association and the prolonged case, the viewer may assume a murder has occurred here, too. But the title remains honest, revealing Triet’s theme that objectivity does not exist, and how often we choose to believe something based on assumptions, preconceptions, and emotions. If Anatomy of a Fall meanders during its 151-minute runtime before arriving at its destination, all of those seemingly inconsequential moments prove vital in their construction of thorny characters and uncertain inner lives. This is a film of intelligence and dimension, marked by a wry sense of humor, and shaped by a thoughtful awareness of human complexity and the faulty systems we have in place to understand it.

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on November 7, 2023.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review