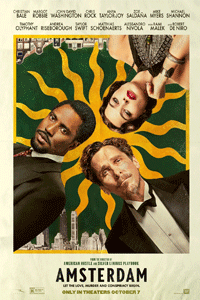

Amsterdam

By Brian Eggert |

While fascism spread across Europe in the early 1930s, many in the United States thought that Hitler and Mussolini had the right idea. Some Americans were sympathizers, convinced by Nazi spies sent from Germany to promote the fascist cause. Others had the same idea or felt emboldened by the examples of European dictators, and then formed fascist groups of their own, including the Black Legion, the Christian Front, and the America First Committee. Not only did these organizations maintain an isolationist stance in the first years of World War II, but they also used hateful remarks to target Jewish, African American, and other minority groups. Even powerful so-called American heroes, from Henry Ford to Charles Lindbergh, advocated for these ideologies and sought to build sometimes very profitable bridges with fascistic European leaders, all while attempting to normalize fascism in the U.S. to further both their political and financial agenda. But the question is: What does any of this have to do with Amsterdam, writer-director David O. Russell’s ensemble comedy, murder mystery, conspiracy thriller, and existential treatise on love and art?

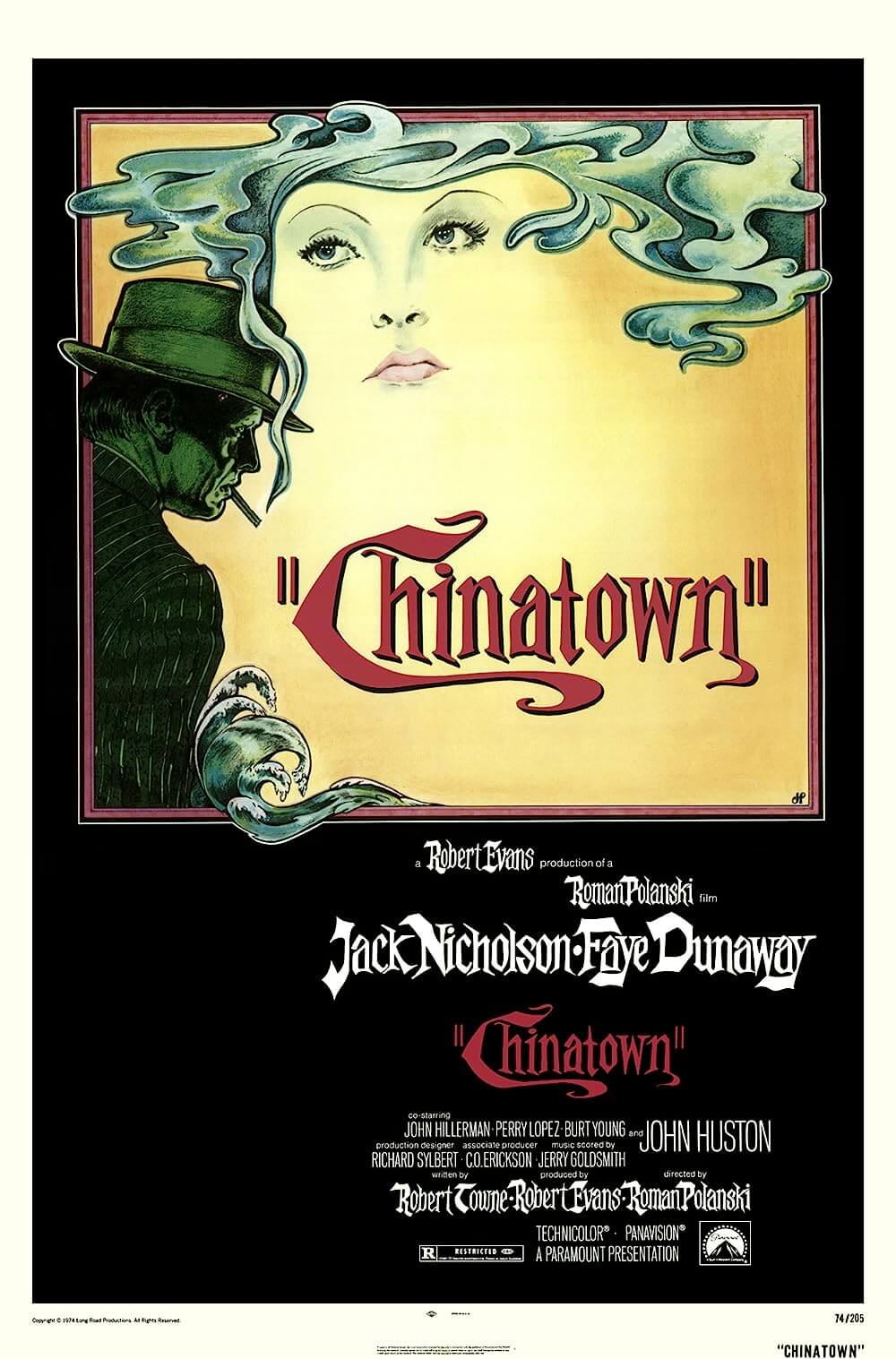

In the film’s roundabout way that owes much to Chinatown (1974), Amsterdam begins with a simple investigation and unfolds into an intricate story about power and wealth. It’s set in New York in the early 1930s—with occasional flashbacks to the Great War—during a time when most Americans had no idea of what was snowballing in Europe. It was a time of relative innocence and happiness between wars: “The good part” of life, as one character describes it, epitomized by the titular capital city of the Netherlands. There, the film’s three main American characters form an unshakable bond after the First World War: Burt (Christian Bale, once again proving his knack for comedy), a half-Jewish doctor who lost an eye in the war and now concocts homemade painkillers to help wounded veterans; Harold (John David Washington), a decorated ex-soldier who becomes a lawyer; and Valerie (Margot Robbie), a manic pixie dream nurse and artist who falls for Harold—a relationship that would never be accepted back home. For them, Amsterdam is a state of mind, just as Chinatown was for Jake Gittes, except more positive. It’s a blissful postwar period where the three of them danced, created art, lived, and loved without any concern for politics or intolerance. But that was in 1918, and their trio eventually dissolved.

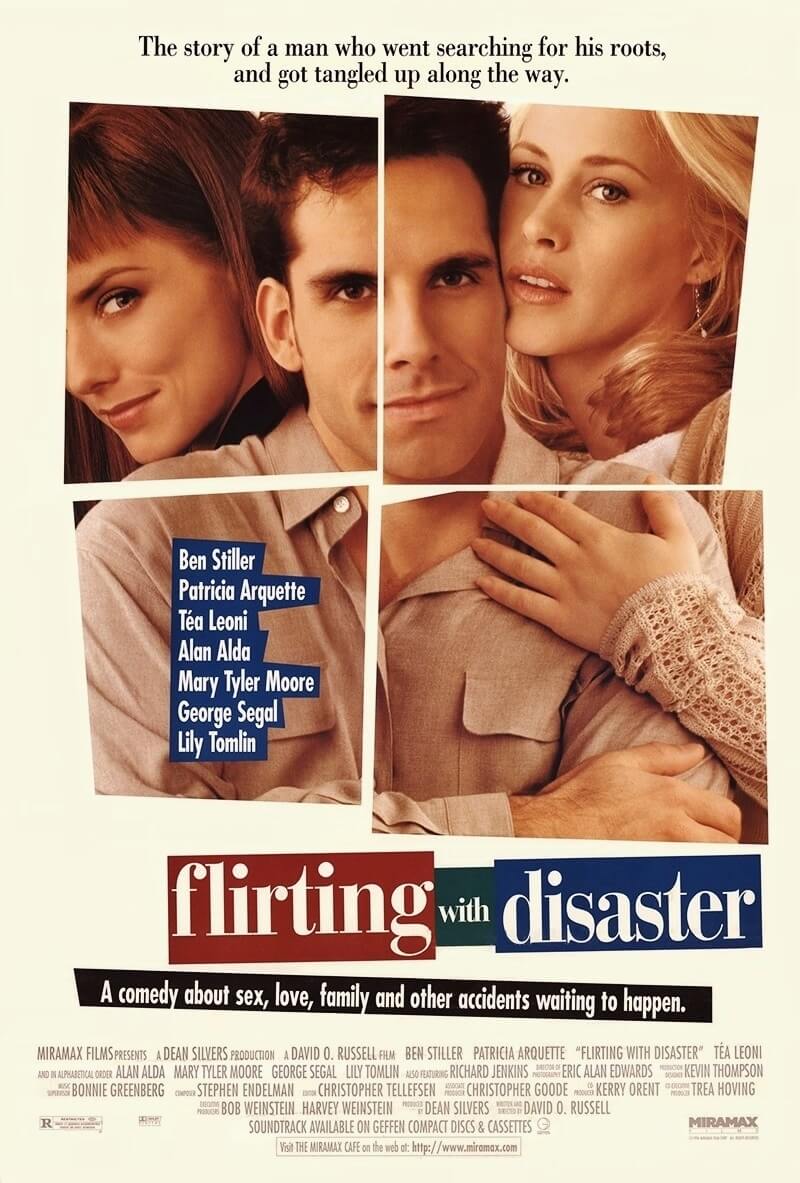

Before establishing his film’s Amsterdam metaphor in a flashback, Russell applies his frenzied, improvisational energy to these based-on-a-true-story proceedings. “A lot of this really happened,” the opening titles inform. Indeed, the story draws from an actual attempted coup d’état to overthrow President Roosevelt in 1933. But Russell and editor Jay Cassidy imbue scenes with dizzying and modern energy, recalling the director’s work from Flirting with Disaster (1996), Silver Linings Playbook (2011), and American Hustle (2013). Russell’s brand of organized chaos may feel anachronistic in a period setting, especially one set before the 1960s, before radical forms of filmmaking started to emerge and defy the tradition of quality in period pieces. Still, the mayhem resembles a Hawksian screwball comedy, complete with recurring pratfalls where Burt hits the ground, and his glass eye pops out onto the floor. But Russell’s zany energy adopts a manner that he also deployed in his best film, Three Kings (1999), in that the humorous setup soon has more serious implications. It’s all augmented and rendered borderline dreamy by Emanuel Lubezki’s gorgeous, color-drained cinematography, which uses a roving camera, close-ups, wide-angle lenses, and low angles to suggest the topsy-turvy events.

Before establishing his film’s Amsterdam metaphor in a flashback, Russell applies his frenzied, improvisational energy to these based-on-a-true-story proceedings. “A lot of this really happened,” the opening titles inform. Indeed, the story draws from an actual attempted coup d’état to overthrow President Roosevelt in 1933. But Russell and editor Jay Cassidy imbue scenes with dizzying and modern energy, recalling the director’s work from Flirting with Disaster (1996), Silver Linings Playbook (2011), and American Hustle (2013). Russell’s brand of organized chaos may feel anachronistic in a period setting, especially one set before the 1960s, before radical forms of filmmaking started to emerge and defy the tradition of quality in period pieces. Still, the mayhem resembles a Hawksian screwball comedy, complete with recurring pratfalls where Burt hits the ground, and his glass eye pops out onto the floor. But Russell’s zany energy adopts a manner that he also deployed in his best film, Three Kings (1999), in that the humorous setup soon has more serious implications. It’s all augmented and rendered borderline dreamy by Emanuel Lubezki’s gorgeous, color-drained cinematography, which uses a roving camera, close-ups, wide-angle lenses, and low angles to suggest the topsy-turvy events.

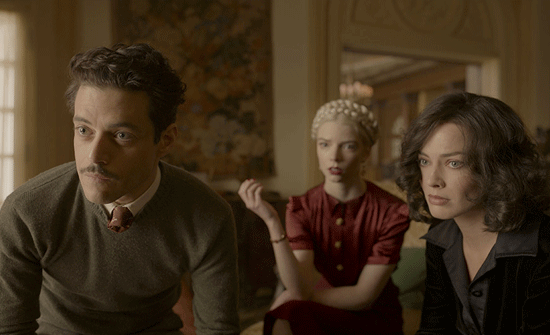

The plot gets rolling when Elizabeth (Taylor Swift) retains Harold’s law firm to acquire a last-minute autopsy on her dead father, Burt and Harold’s former General, Senator Meekins (Ed Begley, Jr.). The Senator died just after returning from a trip to Europe, and Elizabeth suspects foul play. So Harold enlists Burt, and, with the help of Burt’s colleague Irma (Zoe Saldaña), they determine that Meekins was poisoned. But why? When Burt and Harold try to ask Elizabeth, she’s killed in front of them by a mysterious man (Timothy Olyphant), who convinces a white crowd that the one-eyed Jewish doctor and Black lawyer did it. Now on the run from two detectives—Burt’s sympathetic veteran friend (Matthias Schoenaerts) and a flat-footed cop with an inferiority complex (Alessandro Nivola)—Burt and Harold attempt to secure help from Burt’s estranged wife, Beatrice (Andrea Riseborough). Her family’s high society ties suggest the secretive and ultra-wealthy Voze family might be able to help. When Burt and Harold visit the Vozes, siblings Tom (Rami Malek) and Libby (Anya Taylor-Joy), they’re also reconnected with their long-absent friend, Valerie, who disappeared years earlier.

Russell’s screenplay zig-zags in so many directions that it’s easy to see why anyone would feel lost or frustrated while watching Amsterdam, similar to how many responded to his underrated I Heart Huckabees (2005). It’s a challenge to keep track of the various plotlines until their interconnection becomes apparent. But as ever with Russell, there’s a method to his madness. His films tend to play like an optical illusion poster that doesn’t reveal its image unless you relax your eyes. However, until the big picture emerges, we’re caught up in the wild performances, individual set pieces, and moment-to-moment confusion—even among the characters. Burt periodically asks, “What’s happening?” It’s a good question, but not one without an answer, similar to the labyrinthine plot of Chinatown. Even so, it doesn’t help that the romantic subplots (between Burt and Irma, Burt and Beatrice, Harold and Valerie) generally feel underdeveloped. The story also meanders in the middle while our protagonists connect the dots between a white nationalist group called “The Committee of the Five” and their attempt to convince the no-nonsense General Dillenbeck (Robert De Niro) to overthrow Washington D.C., followed by an attempt to stop them.

Much like Russell’s last few films, Amsterdam boasts an impressive ensemble, the most star-studded in recent memory and second in his career only to American Hustle. In addition to those players mentioned, Michael Shannon and Mike Myers star as American and U.K. intelligence officers, respectively—the latter behind blue color contacts, a blonde wig, and his same proper British accent from Inglourious Basterds (2009). Chris Rock also appears as Harold’s assistant, doing his hilarious schtick with commentary on how America is a thankless place for people of color. When the viewer isn’t charting the constellations of stars, we’re racing to keep up with Russell’s shifting perspectives and madcap situations. If the jazzlike arrangement wasn’t enough, Burt and Harold each narrate the film at various points in a style akin to Martin Scorsese’s gangster pictures, often leaping between 1918 and 1933. The film’s energy consists of flowing ideas and a fluid structure that comes together in a strange alchemy, as most of Russell’s films do. The main flaw is that Amsterdam often feels repetitive in its dialogue, particularly Burt’s remarks about following “the wrong god home” or Valerie and Harold’s earnest refrain “Amsterdam,” which means more to them than the audience. Perhaps such reiterations are a way of giving the viewer some consistency through the head-spinning plot machinations.

Much like Russell’s last few films, Amsterdam boasts an impressive ensemble, the most star-studded in recent memory and second in his career only to American Hustle. In addition to those players mentioned, Michael Shannon and Mike Myers star as American and U.K. intelligence officers, respectively—the latter behind blue color contacts, a blonde wig, and his same proper British accent from Inglourious Basterds (2009). Chris Rock also appears as Harold’s assistant, doing his hilarious schtick with commentary on how America is a thankless place for people of color. When the viewer isn’t charting the constellations of stars, we’re racing to keep up with Russell’s shifting perspectives and madcap situations. If the jazzlike arrangement wasn’t enough, Burt and Harold each narrate the film at various points in a style akin to Martin Scorsese’s gangster pictures, often leaping between 1918 and 1933. The film’s energy consists of flowing ideas and a fluid structure that comes together in a strange alchemy, as most of Russell’s films do. The main flaw is that Amsterdam often feels repetitive in its dialogue, particularly Burt’s remarks about following “the wrong god home” or Valerie and Harold’s earnest refrain “Amsterdam,” which means more to them than the audience. Perhaps such reiterations are a way of giving the viewer some consistency through the head-spinning plot machinations.

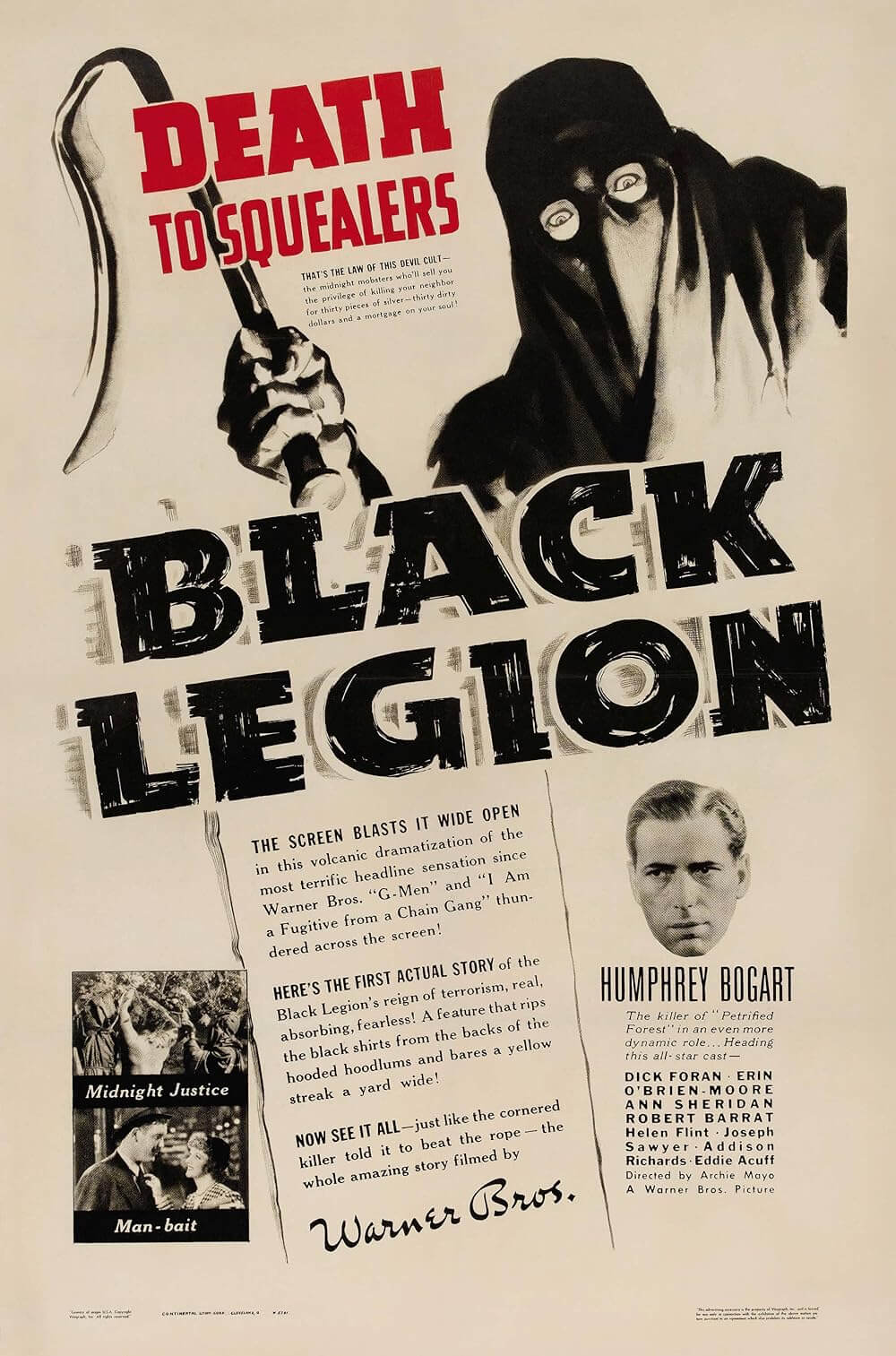

Amsterdam has been subject to some of the worst reviews of Russell’s career (though, I suspect some critics may be reviewing the director as a human being and less so the movie). Regardless, his picture reminded me of so many pre-World War II films, often made by Warner Bros., that sought to expose the dangers of fascism—not because the U.S. government had enlisted the studios for propagandistic purposes (that would come after Pearl Harbor), but because the filmmakers and studio heads felt passionate about taking an anti-fascist stance. And so, Amsterdam resembles films such as Black Legion (1937) and Foreign Correspondent (1940), and it presents itself as a cautionary tale for our times—when corporate interests continue to influence political leaders for control. “What’s more un-American than a dictatorship built by rich people?” asks De Niro’s General Dillenbeck. Post-Trump, the question comes a little late, but the threat remains persistent in how history repeats itself today. But that aside, Russell ends his film with an idealistic message that emerges from the titular metaphor, yearning for love and artistic creation over a fanatical allegiance to politics, greed, and power. After the film’s many impassioned and politicized speeches, like those in another antifascist film, The Great Dictator (1940), the notion feels like an afterthought, albeit a heartfelt one.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review