Reader's Choice

David Bryne’s American Utopia

By Brian Eggert |

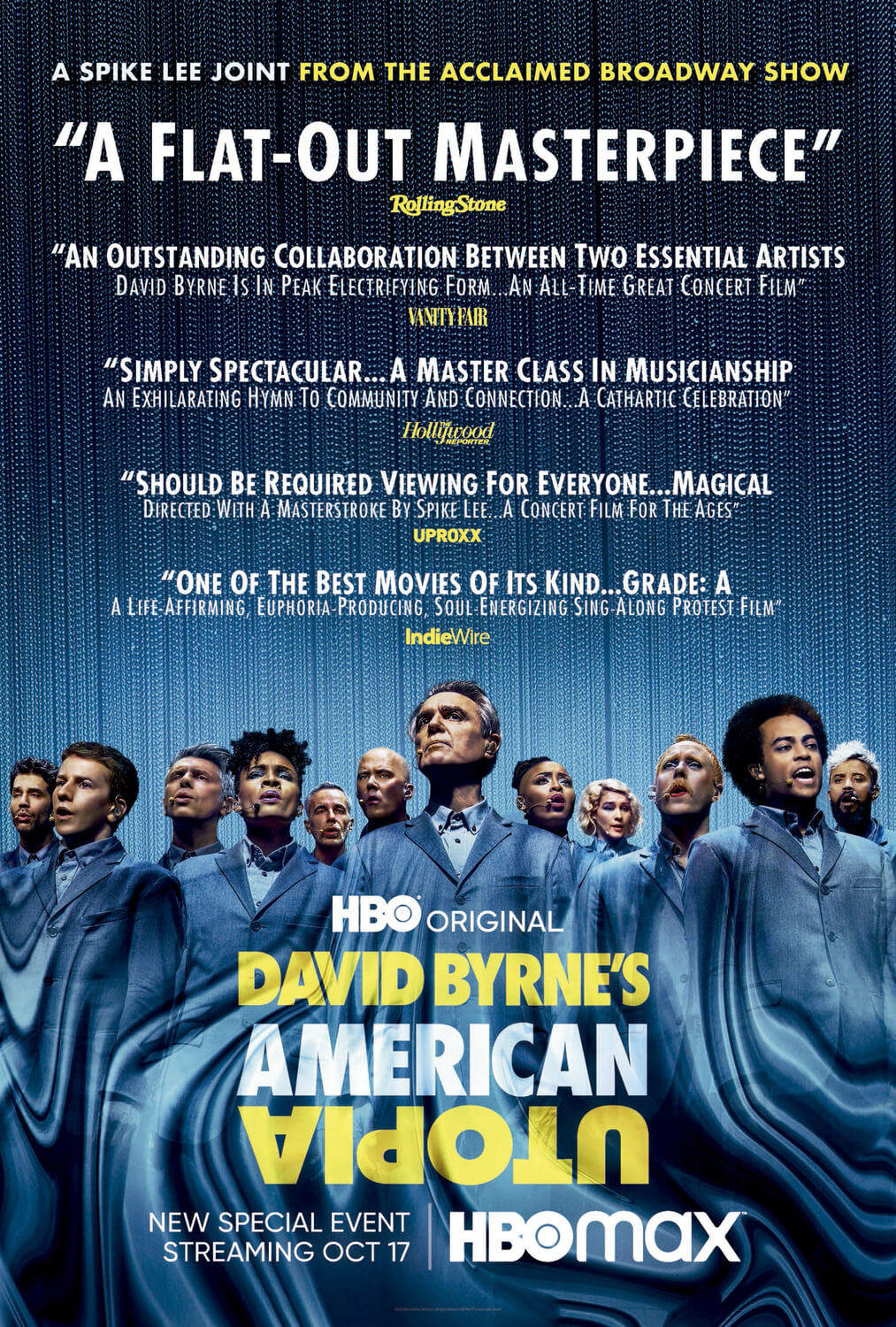

At one point in the concert film American Utopia, David Byrne thanks his audience “for leaving your homes.” Watching in the midst of a pandemic, where going to either a live performance or cinematic exhibition remains ill-advised, I felt the sting of our current predicament. It’s not only that I had to watch the film, directed by Spike Lee, at home on a television, on HBOMax, instead of at a packed theater. It’s that I also vividly remember seeing the show live in Madison, Wisconsin, a few months after the release of Bryne’s 2018 album, also called American Utopia. The live show was incredible, unlike any other concert. But similar experiences may not be possible in the near future. And it’s going to be some time before I feel comfortable assembling with hundreds of other people again—much less dancing, sweating, and breathing alongside them. Still, I couldn’t help but feel overjoyed by those memories and the sheer pleasure of viewing this film. That simultaneous feeling of exhilaration and melancholy is what American Utopia is all about—it’s a celebration of the mixed bag that is America today. Hopeful for the future and commenting on the grim present with stark irony, the film reveals that Bryne and Lee’s sensibilities are in perfect alignment.

From the outset, it’s obvious that American Utopia will not be your average concert film. Byrne and his band of 11 performers appear on a square stage, surrounded on three sides by thin, tinsel-like chains. Each musician dons the same gray, sharply tailored suit and appears barefoot on the empty stage, each carrying their instrument—whether it be a traditional electric guitar on a strap or a body-mounted percussive apparatus. Most of the various drums require no chords, whereas everything electric uses remote technology, freeing each musician to dance in elaborately staged choreography. The musicians regularly step behind the chains when not needed or to exchange their instruments. All the while, Tendayi Kuumba and Chris Giarmo serve as dancers and backup vocalists—although everyone sings—and they almost steal the show from Bryne with their dazzling movements and expressive faces. Overall, the dance feels organized yet also spontaneous, with Busby Berkeley synchronization and the freedom of improvisational movement. Only after seeing both the live show and the film does the intentionality of every gesture become apparent. The result feels more like living installation art than a concert—a blend of dance, music, performance, and socially conscious messaging.

It’s not the first time Bryne has redefined the concert film. In 1984, Bryne’s band Talking Heads released what is arguably the finest of its kind ever made, Stop Making Sense, directed by Jonathan Demme. Like much of the band’s output at the time, the film was a declaration of individuality through surreal lyrics and performance, rallying against an increasingly conformist Reagan-era America. Using some of the same songs, American Utopia reaffirms those ideals. But rather than a statement about individuality, it asks that we look at other people, not the surfaces or objects that would otherwise define them. Both films hope to define the world by prompting questions about who we are and why we do the things we do. Only when we begin this dialogue with ourselves and others can we confront what is wrong with the world and correct it. Bryne arrives at this theme both when he addresses the audience and his selection of songs—half of them come from older solo and Talking Heads albums, half from American Utopia. What’s strange and also brilliant about this theme is how Bryne repurposes classic songs like “Blind” and “Slippery People” and “Burning Down the House” with a new context, imbuing them with newfound relevance.

It’s not the first time Bryne has redefined the concert film. In 1984, Bryne’s band Talking Heads released what is arguably the finest of its kind ever made, Stop Making Sense, directed by Jonathan Demme. Like much of the band’s output at the time, the film was a declaration of individuality through surreal lyrics and performance, rallying against an increasingly conformist Reagan-era America. Using some of the same songs, American Utopia reaffirms those ideals. But rather than a statement about individuality, it asks that we look at other people, not the surfaces or objects that would otherwise define them. Both films hope to define the world by prompting questions about who we are and why we do the things we do. Only when we begin this dialogue with ourselves and others can we confront what is wrong with the world and correct it. Bryne arrives at this theme both when he addresses the audience and his selection of songs—half of them come from older solo and Talking Heads albums, half from American Utopia. What’s strange and also brilliant about this theme is how Bryne repurposes classic songs like “Blind” and “Slippery People” and “Burning Down the House” with a new context, imbuing them with newfound relevance.

The show’s energetic mood has been seen as optimistic, but there’s a deep well of cynicism here too. Perhaps that’s why Lee was attracted to the project. As a dramatic filmmaker and documentarian, Lee regularly confronts the uglier side of humanity and race in America, albeit with the most engaging and hopeful style imageable. Think of Do the Right Thing (1989), Bamboozled (2000), or BlacKkKlansman (2018), and you think of challenging subjects portrayed with vibrant aesthetics. It seems natural that Bryne reached out to Lee to direct. Bryne’s choice of songs characterize American culture today, whether it’s the empty consumption of television, the great societal reflector, with “I Should Watch TV” from Love This Giant, or our collective identity crisis with “Once in a Lifetime” from Remain in Light. Between songs, Bryne addresses the audience to talk about issues of the day, such as poor voter turnouts. He also alternates moods between expressions of creative freedom with “I Dance Like This” to lamentations about gun violence in “Bullet.”

Lee’s visual treatment captures the choreography from a bird’s eye view, up close and personal, or in expressive flourishes. Playfully, he tilts the frame at one point to suggest a relationship between the camera and the stage’s stability, as if rocking the boat. Elsewhere, he accents the show’s lighting with a low angle to emphasize a high shadow or stark cutting to augment a strobe sequence. His signature peaks with Bryne’s cover of a Janelle Monáe song, “Hell You Talmbout.” Although Bryne provides the lead vocals on most songs (aside from “I Zimbra”), the entire group sings in unison for Monáe’s searing, simple method of naming African American victims of racial violence, most of them at the hands of police. Names from Emmett Till to Eric Garner to Trayvon Martin are accompanied by a sudden break from the show. Lee cuts to an image of the victim held by a family member (when possible), accompanied by red titles that list their name, birth date, and death date. It’s a sobering moment when Lee fills the screen with dozens of names, “and too many more.” After breaking us down, American Utopia leaves the viewer with qualified buoyancy, transitioning into the hopeful “One Fine Day.”

After the concert tour to promote the American Utopia album, the show opened on Broadway in October 2019. Its limited engagement lasted the planned four months, and another run is set to open in September 2021. Lee shot the film at the Hudson Theater, using a small contingent of camera operators overseen by the director of photography, Ellen Kuras. It’s an intimate venue with a capacity of 970 seats (the Madison show was equally close-quartered). For much of the performance, both the audience and camera operators remain unseen; Lee keeps his camera pointed at Bryne and company, finding unique ways to frame the ever-moving group. But then, there’s a sequence during the final song, “Road to Nowhere” from Little Creatures, where Lee breaks this pattern. Byrne and his crew march into the crowd, and the formality of the stage show gives way to a joyous communal dance. At the same time, camera operators cannot help but catch glimpses of one another—some with massive cameras mounted on their shoulders, some with handheld devices no larger than a smartphone. The togetherness of the sequence is unmistakable. But there’s that sting again.

After the concert tour to promote the American Utopia album, the show opened on Broadway in October 2019. Its limited engagement lasted the planned four months, and another run is set to open in September 2021. Lee shot the film at the Hudson Theater, using a small contingent of camera operators overseen by the director of photography, Ellen Kuras. It’s an intimate venue with a capacity of 970 seats (the Madison show was equally close-quartered). For much of the performance, both the audience and camera operators remain unseen; Lee keeps his camera pointed at Bryne and company, finding unique ways to frame the ever-moving group. But then, there’s a sequence during the final song, “Road to Nowhere” from Little Creatures, where Lee breaks this pattern. Byrne and his crew march into the crowd, and the formality of the stage show gives way to a joyous communal dance. At the same time, camera operators cannot help but catch glimpses of one another—some with massive cameras mounted on their shoulders, some with handheld devices no larger than a smartphone. The togetherness of the sequence is unmistakable. But there’s that sting again.

During one of Byrne’s introductions, he talks about the song “Everybody’s Coming to My House” from his latest album. He admits that his version makes it sound like the lyric “Everybody’s coming to my house/and I’m never gonna be alone/and they’re never gonna go back home” is a nightmare scenario. If his tunes like “Civilization” are any indication, Bryne needs solitude to recharge his batteries after socializing (he and I have that in common), so the idea of a never-ending party is somewhat disturbing. Alternatively, Bryne notes that a choir from the Detroit School of Arts covered his song, and their version sounds more inviting, as though a party that never stops is something to embrace. American Utopia acknowledges that comfort zones sometimes need to be breached to make progress as a whole, that we all need to get better at dealing with our social anxieties, presumptions, and empathizing with others. Even if the idea of a utopia remains impossible, we’re all in it together, so we may as well try to identify and come closer to one another.

(Note: This review was suggested by supporters on Patreon.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review