American Hustle

By Brian Eggert |

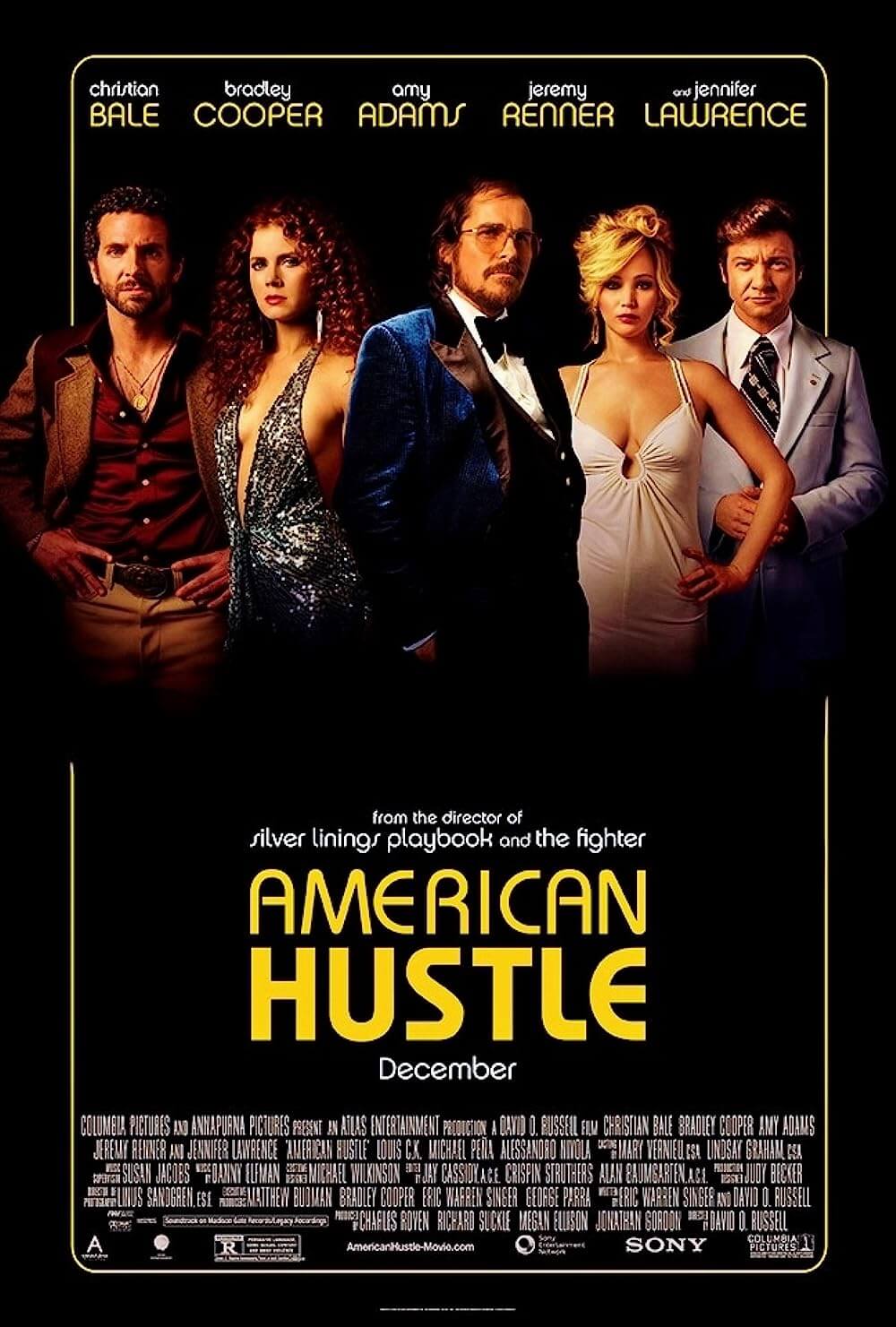

“We’re all conning ourselves one way or another just to get through life,” observes the pudgy grifter Irving Rosenfeld. In the first scene of American Hustle, David O. Russell’s comic and cinematically bravado take on the Abscam scandal of the late 1970s and early 1980s, Irving, embodied by Christian Bale, preps his intricate comb-over in the mirror. He secures a frizzy thatch to his bare scalp with glue, folds inches-long hair over the top to create the illusion of volume, and hardens the absurd coif with a liberal application of hairspray. Along with his brown-tinted, gold-rimmed glasses and flashy three-piece suit, Irving’s style seems like a caricature, but this look is what he needs to walk into a room alongside his partner and an undercover FBI agent to scam a powerful politician. Irving cons himself into believing that no one notices his unflattering appearance, and he functions—flourishes even—because of it. In some respect, each of the central characters in Russell’s hilarious, giddily virtuoso film deceives themselves to gain an advantage through varied means: the illusion of their appearance, the certainty of affection through manipulation, or the simple notion that they’re the smartest person in the room.

Originally called “American Bullshit”, the screenplay by Eric Singer and Russell satirizes history through a cavalcade of 1970s character types and outrageous circumstances of which, as a pre-title informs without the promise of a factual representation, “Some of this actually happened.” Indeed, Irving is based on Melvin Weinberg, a real-life Long Island con artist who struck a deal with the FBI in 1978 to avoid a prison sentence for fraud. Weinberg agreed to help the feds organize an elaborate sting operation that would capture political corruption during videotaped meetings in a posh hotel suite. To entrap Washington politicians into accepting bribes in exchange for their influence, the FBI created an ersatz company in Abdul Enterprises, Ltd. and its fake Arab sheikh backer. More than ten political figures were convicted, including a United States senator and six members of Congress. Singer and Russell’s script marries an enthralling, high-stakes gambit like The Sting with a screwball farce. As a result, American Hustle may offer only a rickety historical background, but it nevertheless concerns itself more with the ensemble of characters who, while also steeped in self-deception, make their business by conning in one form or another.

Russell, whose idiosyncratic comedies have impressed since the early 1990s (see Flirting With Disaster or I Heart Huckabees), has received widespread regard in recent years as director of The Fighter and Silver Linings Playbook. Despite his temperamental reputation in the past, he’s transformed into a prestige-worthy filmmaker capable of wrangling incredible casts and large audiences. Here, Russell reteams with Amy Adams and the Oscar-winner Bale from The Fighter; he also secured once again Bradley Cooper, Jennifer Lawrence, and (in an uncredited cameo) Robert De Niro from Silver Linings Playbook. The director’s casting—which also includes Jeremy Renner as Carmine Polito, a fictionalized version of Angelo Errichetti, mayor of Camden, New Jersey, and state senator—has never been better. For example, in a small supporting role, Russell assigns a pitch-perfect Louis CK as a by-the-book FBI suit, an abused and overpowered victim played with CK’s achingly droll humility. The casting is brilliant, just brilliant.

Russell, whose idiosyncratic comedies have impressed since the early 1990s (see Flirting With Disaster or I Heart Huckabees), has received widespread regard in recent years as director of The Fighter and Silver Linings Playbook. Despite his temperamental reputation in the past, he’s transformed into a prestige-worthy filmmaker capable of wrangling incredible casts and large audiences. Here, Russell reteams with Amy Adams and the Oscar-winner Bale from The Fighter; he also secured once again Bradley Cooper, Jennifer Lawrence, and (in an uncredited cameo) Robert De Niro from Silver Linings Playbook. The director’s casting—which also includes Jeremy Renner as Carmine Polito, a fictionalized version of Angelo Errichetti, mayor of Camden, New Jersey, and state senator—has never been better. For example, in a small supporting role, Russell assigns a pitch-perfect Louis CK as a by-the-book FBI suit, an abused and overpowered victim played with CK’s achingly droll humility. The casting is brilliant, just brilliant.

Russell specializes in ensembles, his frenetic energy passing amid hugely talented actors in larger-than-life performances. And none of them, surprisingly, goes too far over the top in American Hustle. But then, the entire film exists within a world of excessive vibrancy. Bale’s appearance as the self-made con artist and loan shark Irving is another transformative role for this intense method performer; he added 40 pounds to his frame and walked with a hunch throughout the production, causing some back issues offscreen. Adams stars as Irving’s paramour Sydney, who uses the alias Lady Edith, and whose on-and-off British accent recalls Barbara Stanwyck in Preston Sturges’ romantic con-game The Lady Eve (1941). Irving and Sydney are involved in a lucrative scam in which they sell art forgeries and accept money for faux investments in nonexistent overseas companies. When they’re caught by Richie DiMaso (Cooper, under a riotous perm), an unstable FBI Agent, they’re forced to help Richie catch other professional hustlers. On the sidelines is Irving’s young and estranged wife Rosalyn (Lawrence), whose beauty and unpredictable personality clash like her description of the scent of her favorite nail polish: “Sweet and sour, like flowers, but also rotten, like garbage.”

In a wildly funny and stressed tale populated by schemers, liars, and self-deceivers, Irving finds himself juggling pressures from his FBI handler, his on-the-brink girlfriend, and his manipulative wife. But the film’s structure doesn’t fall on a single protagonist; in fact, in a touch (not the only one) reminiscent of Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas or Casino, multiple narrators relay the events and our sympathies shift throughout. Richie seems like an ambitious Agent, except his professionalism comes into question when he begins sniffing after Sydney. And she plays Richie like a harp, until his manic behavior and unchecked drive set their sights on a bigger mark, one that gets all of them involved not only with politicians, but the Mafia. They begin by targeting Carmine Polito, but Richie figures why stop there when they could take down government officials and organized crime too? Irving, trapped between his fear of prison time and Richie’s unbridled overreaching that may get them all killed, squirms. In his defense, Irving’s scams and romantic duplicitousness may be flaws, but he’s genuinely affected by his feigned “friendship” with Carmine, and he also genuinely loves Rosalyn’s young boy fathered by another man. Meanwhile, Rosalyn’s loose cannon approach to life hooks her to the arm of a charming mobster (Jack Huston), to whom she says far too much about her husband’s dealings.

Russell is a master of organized chaos, from the overlapping dialogue in Flirting With Disaster and Silver Linings Playbook, to the blend of intellectual philosophy and filthy humor in I Heart Huckabees, to the actionized political war comedy tone of Three Kings. He orchestrates a whirlwind of unbalanced characters in American Hustle, injecting a pointed 1970s style to rival the visual element and satiric edge of P.T. Anderson’s Boogie Nights. Every aspect of the production exudes detail. Production designer Judy Becker’s flashy décor of yellows and browns, and the deep necklines of Michael Wilkinson’s costumes realize the period in extraordinary flair. The soundtrack is filled with ‘70s hits, jazzy songs, and even some disco. Just like Anderson’s film, Russell pokes fun at the shabby excess of the ‘70s as the decade fades into the ‘80s. But, as suggested above, Russell’s greatest influence is Scorsese, with a dash of Sidney Lumet’s New York pictures of the ‘70s (Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon) to boot. Cinematographer Linus Sandgren replicates Scorsese’s frequent use of quick rushes and zooms (established by Michael Ballhaus on After Hours and maintained through The Departed). Along with the varied perspective narration, Russell adopts some of Scorsese’s technical tricks and narrative devices; however, the neurotic humor and head-case characters are pure David O. Russell.

In a film defined by its exceptional performances, none of them stand out insofar that all of them deserve endless praise. Almost completely untested in comedic roles, Bale delivers a masterful performance far beyond that of his physical makeover. Bale’s portrayal is somehow soulful and absurd at the same time, as his character questions what he’s doing and wonders if America needs another scandal after the Vietnam War and Watergate. Adams pins down her character’s tricky, sexy charms as wondrously as Stanwyck did in The Lady Eve, and, likewise, makes it look easy. But Sydney’s life of lies has worn her down, and Adams realizes Sydney as an almost tragic figure. In another manic role to rival his turn in Silver Linings Playbook, Cooper’s FBI man appears completely out of his depth both professionally and emotionally, and when things go wrong, the actor’s outbursts are raw comic hysteria. As for Lawrence, Irving describes Rosalyn as “the Picasso of passive-aggressive karate” but she’s also a force of unruly nature, sexual and dangerous. Whether she’s blowing up a “science oven” microwave or furiously housecleaning to “Live and Let Die”, Lawrence’s limited role isn’t quite as dim as Judy Holliday in Born Yesterday (1950), but her monumental blunders and ignorant, spiteful behavior are scene-stealing. Renner is also very good as an idealistic politician who just wants to create jobs and rebuild Atlantic City.

Russell manages to make these characters at once despicable and loveable, complicated and weighty, none of them irredeemable, each of them incurably watchable. Some may consider this the defect of American Hustle, as, just like Silver Linings Playbook, the director somehow devises an unlikely happy ending for his besieged characters. But it’s all exhilarating at a level few directors could maintain for the film’s full 2-hour-and-18-minute runtime. Such a maneuver requires a kind of magic, and Russell demonstrates that he’s a wizard of outcasts and strangely crowd-pleasing conclusions. The enthralling Abscam caper serves as a fascinating pretense in which even more fascinating characters either come apart or maintain impossible composure under unbearable strain, allowing the film’s actors to deliver crazily entertaining performances rooted in what seems like an almost improvised style. Whether spontaneous or carefully planned, Russell’s unique capacity to propel his intelligent work with a hyper, lively quality radiates and leaves you burning from its contagious energy.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review