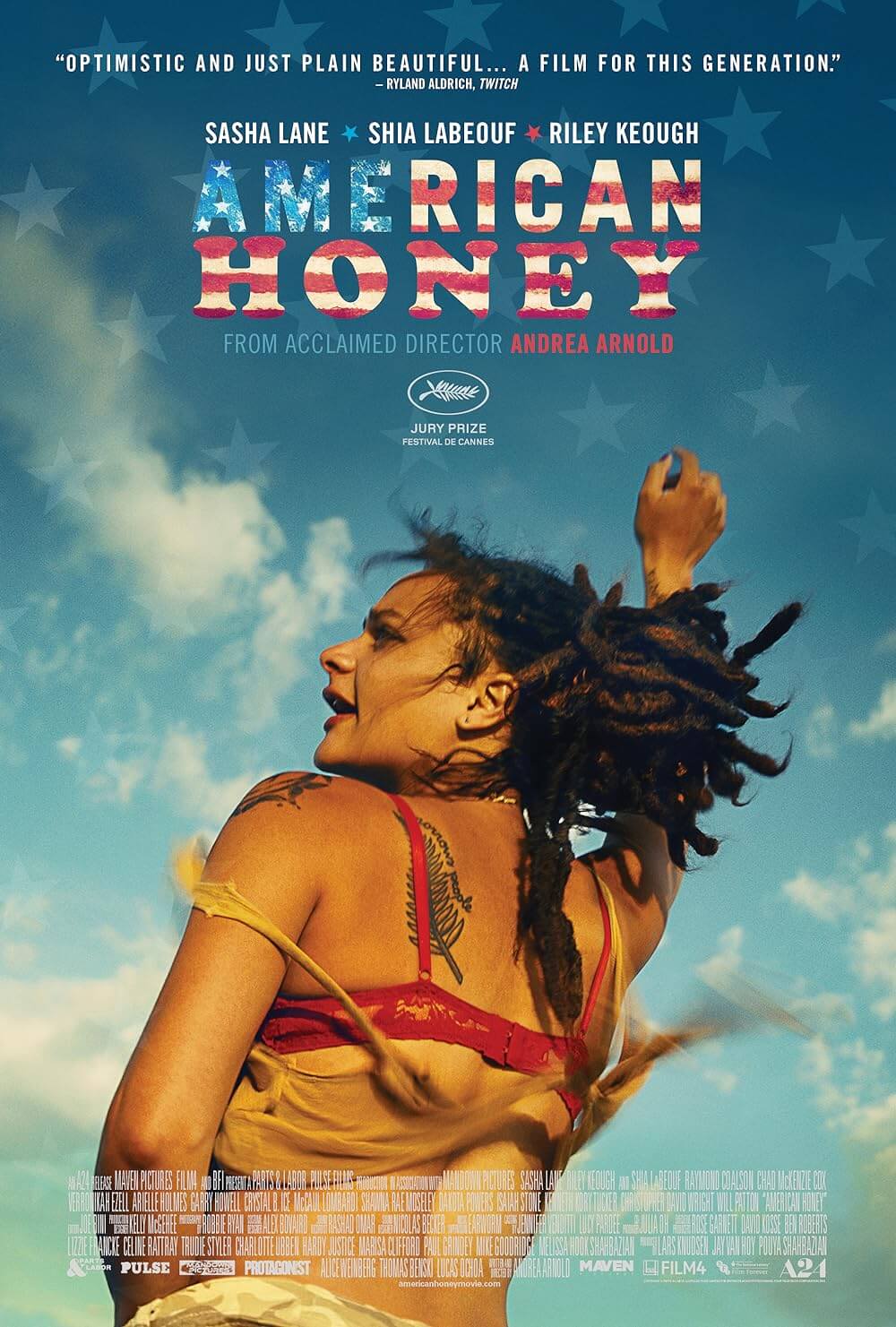

American Honey

By Brian Eggert |

Putting “American” at the beginning of a title has become a tired platitude, in most cases because its usage often feels meaningless when compared to the film’s context. American Hustle could take place almost anywhere, while American Gangster forgets that drug lords are not U.S.-exclusive and have made their homes in countries around the world. In many cases, the “American” of a title isn’t followed by a film about America, per se. Such is not the case with American Honey, the fourth film by British filmmaker Andrea Arnold. Running nearly three hours, Arnold’s elegiac and naked picture functions as a road adventure born of Dickens and Kerouac. It’s at once a coming-of-age drama and a sketch of the American Heartland. Venturing from Oklahoma to Nebraska, Missouri, and the Dakotas, Arnold captures an unromantic representation of thankless social conditions and impulsive behavior—all of it framed by the filmmaker’s tender understanding and rather beautiful portrait-making of her subject. Indeed, American Honey might seem like the work of an observational documentarian if it wasn’t so artfully presented.

Consider the film a modern and Americanized counterpart to Oliver Twist. A young and desperate woman, barely 18, named Star (newcomer Sasha Lane), abandons her coarse family to join a band of unruly teens who sell magazines at truck stops and towns (both privileged and impoverished) along U.S. highways. They’re led by the film’s resident Fagan, a harsh twentysomething named Krystal (Riley Keough), who rides ahead in her convertible, driven by Jake (Shia LaBeouf), her top seller. Krystal gives her workforce cheap motel rooms to share and transportation in a big van, but she takes a cut of their (legitimate?) magazine subscription sales, leaving them with only a quarter of their earnings. Additionally, Krystal has plenty of rules and issues threats if quotas are not met; but ultimately, her band of sellers lives a free-spirited existence. Loud music thumps throughout their van as Star meets her new crew, each oversharing their personal troubles, each bearing a face of hard-won independence and post-traumatic optimism, and all played by an ensemble of inexperienced actors.

Most impressive is Lane, whom Arnold discovered on a beach. Her performance as Star remains frighteningly naïve yet doggedly self-assured, a quality common among her fellow door-to-door sales associates. Star makes impulsive and rash decisions that, in another film, might result in tragedy. At several points throughout, she takes a warning sign ride from just about anybody, either ignoring or blind to the potential danger that could ensue. In a way, Star’s freedom is enviable; her willingness to trust and see the good in people serves her well. But we can imagine that not everyone who accepts a ride from a lone trucker, three upper-middle-class cowboys looking to party, or a horny oil worker ends up so well. American Honey is more episodic and sprawling than to allow itself to become so predictable, plot-oriented, or tragic outright. The film just sort of unfolds, with Arnold and her editor Joe Bini creating the impressionistic, Malickian tone and feel of cinematic wanderlust.

Elsewhere, Star finds herself drawn to Jake, Krystal’s own personal Artful Dodger, in an uncertain romance. LaBeouf gives perhaps the best performance of his career here, evoking the signature cocksureness that defined his early roles, while also remaining unpredictable and carrying some evident wounds that have marked his roles since his breakdown following Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. Alongside the naturalistic turn by Lane, LaBeouf manages to disappear into his eyebrow piercing, braided rattail, and oversensitive jealousy, delivering a performance of rage and passion. Even so, American Honey is far from a love story, as Jake can be just as cruel and selfish, as well as far too accommodating to Krystal. Jake, and the myriad of other, somewhat underdeveloped teens on the magazine bus, feel secondary next to Star, as none of them are so elemental or pure. Instead, it feels like the cast of Larry Clark’s Kids has taken to the road.

Elsewhere, Star finds herself drawn to Jake, Krystal’s own personal Artful Dodger, in an uncertain romance. LaBeouf gives perhaps the best performance of his career here, evoking the signature cocksureness that defined his early roles, while also remaining unpredictable and carrying some evident wounds that have marked his roles since his breakdown following Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. Alongside the naturalistic turn by Lane, LaBeouf manages to disappear into his eyebrow piercing, braided rattail, and oversensitive jealousy, delivering a performance of rage and passion. Even so, American Honey is far from a love story, as Jake can be just as cruel and selfish, as well as far too accommodating to Krystal. Jake, and the myriad of other, somewhat underdeveloped teens on the magazine bus, feel secondary next to Star, as none of them are so elemental or pure. Instead, it feels like the cast of Larry Clark’s Kids has taken to the road.

Long and somewhat messy, Arnold’s sprawling journey on the road marks another of the writer-director’s portraits of a specific time and place. Her 2006 debut Red Road examined a security CCTV operator in Glasgow, Scotland, who obsesses over a man who shaped her past. In Fish Tank (2009), the director peered into the council estates of her hometown in Dartford, where a teenage wannabe dancer finds herself charmed by the affections of her mother’s boyfriend. Arnold’s films often represent their subjects with an unflinching truth about their situation and the worlds they inhabit, backed by a formal austerity that looks deceptively spare. For instance, her 2011 adaptation of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights seems boundless despite its formal choices. Rather than shoot on the misty English countryside in a manner recalling Ang Lee’s idyllic-looking Sense and Sensibility, or even the IMAX scope of Skyfall, Arnold used a boxy 4:3 aspect ratio on Wuthering Heights to convey the limited world afforded Brontë’s classical characters.

For American Honey, Arnold once again limits the frame, resisting the urge to sentimentalize the beauty of the film’s Midwest locations with a wide visual panorama. The reduced frame suggests the restricted perspective of its characters, while the crisp photography by Robbie Ryan (Slow West, and all of Arnold’s other films) looks gorgeous within its clipped presentation. Nevertheless, the characters appear larger-than-life in this limited rectangle—like players in their own music video to the soundtrack’s millennial playlist of Rhianna, Låpsley, Mazzy Star, and even Bruce Springsteen. Lady Antebellum sings the titular tune, and everyone on the bus knows the lyrics, save for Star. Much like Arnold’s presentation, and America itself, Star seems to drift and lose herself in the moment; she gets caught up in her dreams and her group’s inbred camaraderie; she takes unnecessary and often unwise risks. But, in the end, Arnold embraces a damaged form of self-discovery that makes American Honey a marred, if hopeful use of the “America” in its title.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review