American Fiction

By Brian Eggert |

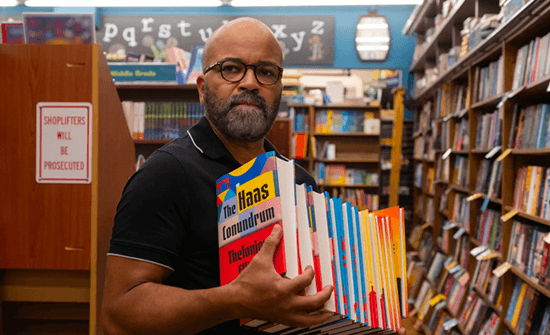

Do you want to be good, or do you want to be popular? That’s one of the many complex artistic questions at the center of Cord Jefferson’s scathing and hilarious American Fiction, a surprisingly tender and even tragic satire that discusses matters of artistic responsibility among creatives. Jeffrey Wright stars as Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, an English professor and critically acclaimed author whose books don’t sell. Tired of publishers, readers, and fellow authors trafficking in buzzwords such as diversity and representation, Monk has become embittered. He probably drinks too much, has been seen crying alone in his car, and, in the opening scene, loses his temper with a white student who was too offended by the n-word to let the lesson proceed. “When did they all become so goddamn delicate,” he wonders aloud. The incident earns him a mandatory, unpaid vacation home to Boston, where Monk grapples with family drama and resolves to act out with a new book. What unfolds seems like a polemic at first, with Monk’s pronouncement, “Okay, let’s begin” in the opening, equating to here beginneth the lesson. But wrapped around the film’s often caustic conversation about race in America, artistic responsibility, and the ethics of representation is a dimensional drama, anchored by a fantastic performance from Wright.

If the trailers sell American Fiction as a wacky farce, the reality is a far more measured character study of Monk. After arriving home, Monk finds his family in quiet disarray, staying in the summer house where their father shot himself. Now his mother (Leslie Uggams) is losing her memory to dementia, and his divorced sister Lisa (Tracee Ellis Ross, a ray of light), full of levity, continues her work at an abortion clinic. A tragedy brings his brother, Clifford (Sterling K. Brown), a newly divorced plastic surgeon from Arizona, home for a funeral. Along with Lorraine (Myra Lucretia Taylor), the family’s kindly housekeeper who receives a lovely subplot, the dynamic between them feels genuine, complete with years of memories and animosities to examine. Staying to resolve some family business, Monk begins to see Coraline (Erika Alexander), a lawyer who lives across the street and has read one of Monk’s books. Meanwhile, his agent, played by John Ortiz, cannot sell his latest manuscript. The publishing industry wants a “Black book,” and Monk, who claims not to believe in race, refuses to kowtow to an intellectually bereft industry.

After hearing an excerpt from the best-selling We’s Lives in Da Ghetto by a fellow Black author Sintara Golden (Issa Rae), and listening to her statements about representation, Monk cannot believe his ears. “Look at what they publish. Look at what they expect us to write,” he says later. How low she must have sunk to pander to an audience of predominantly white women, writing a book he believes was designed “to satisfy the needs of guilt-ridden white people.” And so, stressed about his family and disenchanted by the literary world, he sits down to manufacture a tome of gross stereotypes he calls My Pafology, throwing what white audiences want to see from Black fiction in their face. But to his surprise, Monk, working under a pseudonym, Stagg R. Leigh, receives a $750,000 offer for his story about an eye-patched thug who kills his father, only for the cops to shoot him dead in the end. Soon enough, not only does his facetious book hit stores but it’s optioned by a smarmy producer (Adam Brody) into a Hollywood movie. All the while, he must pretend to be Leigh, an escaped convict on the run from the FBI, which, of course, only adds to the public’s impression of the book’s seeming authenticity.

After hearing an excerpt from the best-selling We’s Lives in Da Ghetto by a fellow Black author Sintara Golden (Issa Rae), and listening to her statements about representation, Monk cannot believe his ears. “Look at what they publish. Look at what they expect us to write,” he says later. How low she must have sunk to pander to an audience of predominantly white women, writing a book he believes was designed “to satisfy the needs of guilt-ridden white people.” And so, stressed about his family and disenchanted by the literary world, he sits down to manufacture a tome of gross stereotypes he calls My Pafology, throwing what white audiences want to see from Black fiction in their face. But to his surprise, Monk, working under a pseudonym, Stagg R. Leigh, receives a $750,000 offer for his story about an eye-patched thug who kills his father, only for the cops to shoot him dead in the end. Soon enough, not only does his facetious book hit stores but it’s optioned by a smarmy producer (Adam Brody) into a Hollywood movie. All the while, he must pretend to be Leigh, an escaped convict on the run from the FBI, which, of course, only adds to the public’s impression of the book’s seeming authenticity.

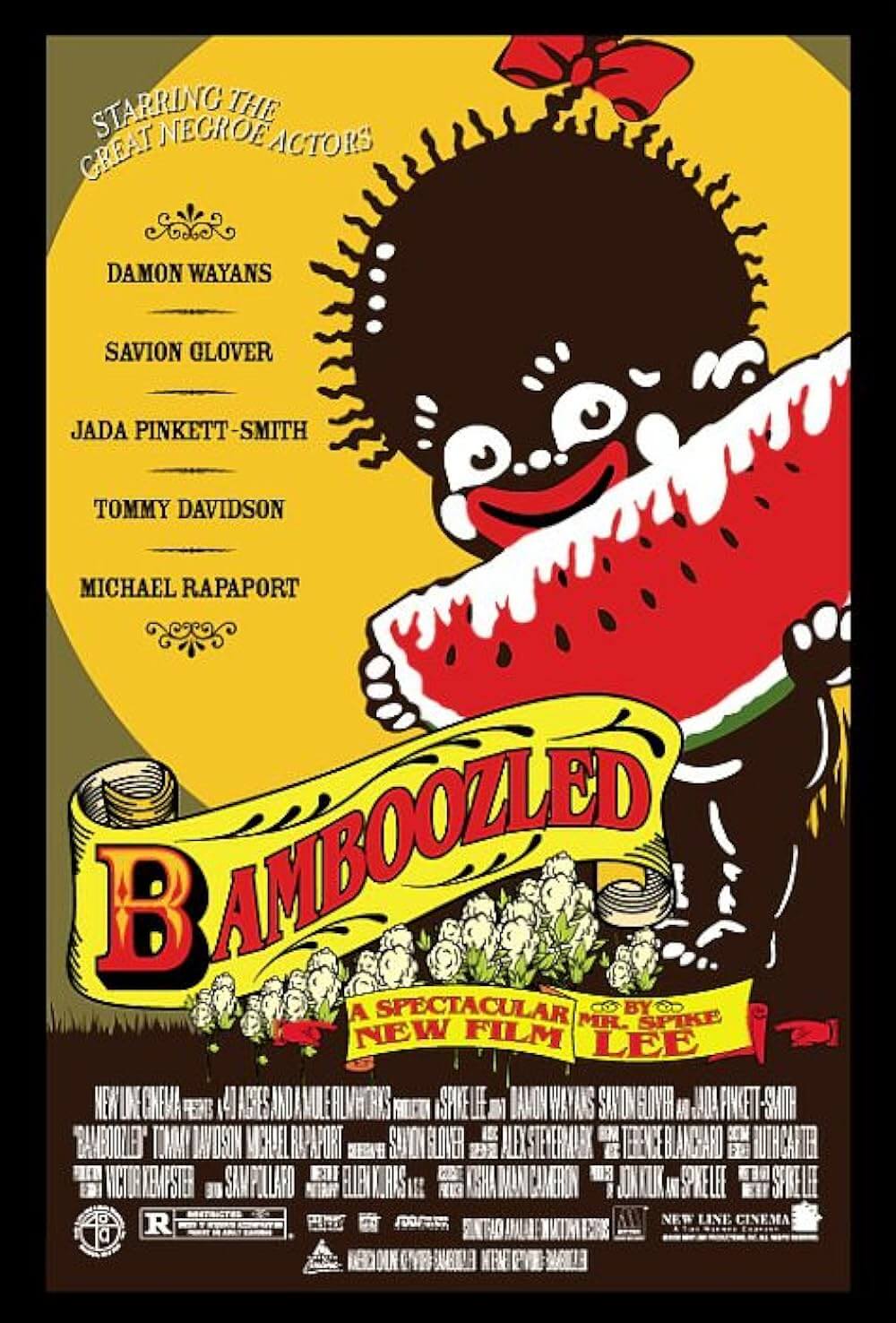

Based on the 2001 novel Erasure by author Percival Everett, the material owes a considerable sum to Robert Townsend’s Hollywood Shuffle (1987) and Spike Lee’s Bamboozled (2000). Both grapple with Black representation in the entertainment industry, the former in movies, the latter in television. Both examples find their respective protagonists wrestling with whether they should contribute to Black stereotypes. In Townsend’s comedy, his struggling actor character refuses to lower himself to that level, and the film itself is a testament to his refusal to play another urban criminal, slave, or Eddie Murphy type. Lee’s film finds Damon Wayans’ TV writer hoping to send a message to his white producer about the danger of Black stereotypes by pitching a new show in which performers of color perform minstrel routines in blackface, but it backfires, and the show goes on TV and becomes a hit. Similarly, in Monk’s case, he can’t imagine anyone would publish his book, so he resolves to demand an absurd title change to Fuck, expecting publishers to lose interest. Instead, it only garners the book more attention from opportunistic publishers, readers, and even the literary establishment. “The dumber I behave, the richer I get,” Monk observes.

If American Fiction’s satirical premise feels too close to Bamboozled to be called wholly original, Jefferson’s screenplay distinguishes itself with acidic wit, brief flights of fancy, and characters who feel three-dimensional. Cord has worked on some of the best television series of the twenty-first century, including Watchmen, The Good Place, Succession, and Station Eleven. This is his first time as a film director, and it’s an accomplished piece of work, less dependent on visuals than words, which is not to discredit cinematographer Cristina Dunlap’s assured lensing. Dunlap’s work has the straightforward appearance of a no-fuss indie, even in its few broad comic moments, most involving Brody’s hilarious caricature of Hollywood scum. When Monk adapts Fuck into a screenplay, Jefferson shows us several iterations of the possible ending, and they’re about as flashy as American Fiction gets. But most of the film relies on Wright’s lived-in performance, his best since Basquiat (1996). Monk wears his intellectual credibility as a shield, yet, as Coraline points out, it’s not admirable to be actively unknowable. Wright terrifically captures the cracks in his character’s armor.

The film is best outside of its satiric broad strokes, in scenes involving Monk’s family and peers. In the former category, Brown is excellent as the defiant Clifford, who, steeped in his own midlife crisis after coming out, confronts how Monk is repeating their father’s lies, anger, and detachment. Elsewhere, a subplot involves Monk serving on a panel of judges to determine a literary award, giving us a slice of how even academia fails to adequately address matters of race and representation. When the panel of judges, which includes Sintara Golden, assesses his book, they call it “real” and “raw,” much to his disbelief. He talks to Sintara about how books like theirs “flatten our lives.” Then again, if they sell, doesn’t every creator have a responsibility to get their work out there and earn a payday? Should individual artists be held responsible for how their work reflects their race? Isn’t that a problem with society and perception, and not the artist? Should creators try to change the system or contribute to and profit from it? Monk says he thinks Black people have the potential to be more. Sintara responds, “Potential is what people see when what’s in front of them isn’t good enough.” The remark stops the conversation in its tracks.

The film is best outside of its satiric broad strokes, in scenes involving Monk’s family and peers. In the former category, Brown is excellent as the defiant Clifford, who, steeped in his own midlife crisis after coming out, confronts how Monk is repeating their father’s lies, anger, and detachment. Elsewhere, a subplot involves Monk serving on a panel of judges to determine a literary award, giving us a slice of how even academia fails to adequately address matters of race and representation. When the panel of judges, which includes Sintara Golden, assesses his book, they call it “real” and “raw,” much to his disbelief. He talks to Sintara about how books like theirs “flatten our lives.” Then again, if they sell, doesn’t every creator have a responsibility to get their work out there and earn a payday? Should individual artists be held responsible for how their work reflects their race? Isn’t that a problem with society and perception, and not the artist? Should creators try to change the system or contribute to and profit from it? Monk says he thinks Black people have the potential to be more. Sintara responds, “Potential is what people see when what’s in front of them isn’t good enough.” The remark stops the conversation in its tracks.

If the two Black authors on the literary award committee agree on anything, it’s that Fuck shouldn’t win the award. But they’re outvoted by the predominantly white panel who “think it’s essential to listen to Black voices right now”—just not Monk’s or Sintara’s voices. Their decision is a pointed moment that gets to the core of how American Fiction dissects the thorny system around Black art, and how it’s consumed, advertised, and commodified, and for whom. Are they stories, or are they “Black Stories”—as, for example, many streaming services would label them—targeted to white audiences? Monk would argue to remove that label, but also, the label helps embolden improvements in diversity awareness and representation. These are complex questions that neither Cord nor Monk attempts to solve, but they’re necessary prompts for a culture where the discourse about representation remains ongoing. While these issues give American Fiction’s approach to satire an intelligent backbone, they’re also paired with the strength and texture of Wright’s performance, which shapes the intimate, character-driven drama at the center. Cord’s film can sometimes feel split between the two threads, but it’s so smart and thoughtfully considered that its structure and similarity to previous satires hardly matter.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review