Reader's Choice

American Factory

By Brian Eggert |

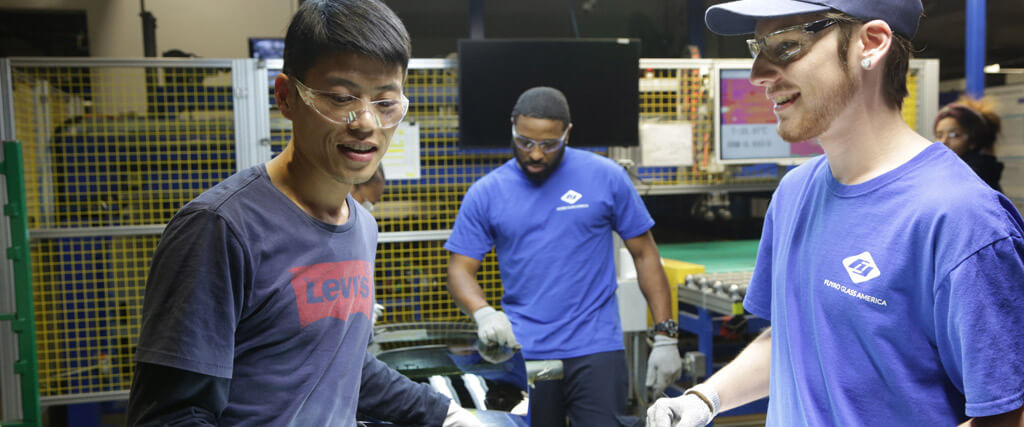

American Factory, the new documentary by Ohio-based filmmakers Steven Bognar and Julia Reichert, picks up a few years after their Oscar-nominated short for HBO, “The Last Truck: Closing of a GM Plant”—which left some 3,000 workers unemployed after the Dayton automobile factory shut down following the 2008 financial crisis. If their short film marked the end of an era in American capitalism, their new feature confronts a more delicate and nuanced situation. In 2014, Chinese magnate Cao Dewang, chairman of Fuyao Group, bought the Moraine Assembly plant once owned by GM and established the latest site of his auto glass division, calling it Fuyao Glass America. At the outset, Cao and his executives talked about enriching the Dayton community with a symbolic partnership between the Chinese company and American workers, some of whom had been out of work since the GM plant closed. But the doc takes an observational approach to chart a series of culture clashes between American and Chinese interests, from work ethic to unionization.

Bognar and Reichert have surprising access to Fuyao employees, machine processes, internal meetings, and Cao, in part because the billionaire wanted to document his success in America with a film. Even so, the filmmakers avoid making a puff piece. Almost immediately, with the ribbon-cutting ceremony at Fuyao where a local senator mentions the importance of worker unions in the United States, union interference threatens to derail Cao’s profit margins. Behind closed doors, Cao tells the company’s leadership, both American and Chinese, that if the unions come in, he’ll shut down the factory. But the prospect of unionization becomes increasingly attractive to the American workers who, after such a long stint of unemployment, are just happy to get back to work. Still, the pay is an issue; they earn half of what they earned from GM. The safety conditions also lack the same checks and balances to which they’re accustomed. Moreover, those who view unions as the answer are seen as troublemakers, and Fuyao brings in anti-union speakers to push the workers in a different direction. And tensions between the workers and the bosses continue to escalate after Cao’s company fails to reach its quotas.

For the first half of American Factory, Bognar and Reichert seem objective and even optimistic about the prospect of a Chinese-run factory on American soil. There are differences between the factory workers, to be sure. When a group of American workers visits the Chinese headquarters to observe their efficient practices, two members of middle management, an American and a Chinese man, discuss their employees: the Chinese operate like machines, adopting a military-style regimentation to their work routine; the Americans are thought to be lazy, unwilling to devote the hours necessary to get the job done. The Chinese businessmen attend their meetings in suits; one of the Americans wears a Jaws t-shirt to the same meetings. But after the day’s assembly, there’s a party where one large American executive must excuse himself after dinner. His eyes filled with tears, he explains that he was struck by the feeling that “we’re one.” It’s either the most tender and hopeful moment in the film, or the guy simply had too much to drink.

There’s a lot of that going around in American Factory, where moments in the film’s fly-on-the-wall technique seem artificial. Some people are too aware of the importance of image today to be unfiltered. Scenes of Cao looking out of windows, as if searching the sky for answers to his company’s success, look laughably staged, like a commercial for an antidepressant. Also, the sound editor inserts effects that raise an eyebrow about the film’s authenticity—for instance, there’s a scene in which some workers exit the factory, and the squeak made by the door is the sound byte of a rusty wrought iron fence that I’ve heard in countless other films. Perhaps this is nitpicky on my part, but it speaks to the produced quality of the film, which, when exposed, raises questions—more than usual—about how much the filmmakers shaped the story. Elsewhere, Bognar and Reichert avoid having a voice in their film. Unlike Michael Moore or Louis Theroux, they remain behind the camera, allowing their images and interviews to speak for themselves. The resulting ambiguity about the doc’s objective enables it to become a conversation piece, the benchmark of most successful documentaries today.

There’s a lot of that going around in American Factory, where moments in the film’s fly-on-the-wall technique seem artificial. Some people are too aware of the importance of image today to be unfiltered. Scenes of Cao looking out of windows, as if searching the sky for answers to his company’s success, look laughably staged, like a commercial for an antidepressant. Also, the sound editor inserts effects that raise an eyebrow about the film’s authenticity—for instance, there’s a scene in which some workers exit the factory, and the squeak made by the door is the sound byte of a rusty wrought iron fence that I’ve heard in countless other films. Perhaps this is nitpicky on my part, but it speaks to the produced quality of the film, which, when exposed, raises questions—more than usual—about how much the filmmakers shaped the story. Elsewhere, Bognar and Reichert avoid having a voice in their film. Unlike Michael Moore or Louis Theroux, they remain behind the camera, allowing their images and interviews to speak for themselves. The resulting ambiguity about the doc’s objective enables it to become a conversation piece, the benchmark of most successful documentaries today.

Certainly, the film mourns the death of industrial jobs that once defined America as an independent and thriving economic power; but times have changed, as signaled by the irony of a Chinese company helping Americans along. More than a statement about countries or even industries, the filmmakers turn massive and complicated issues into a human interest story—they look at workers from both sides, such as a woman who can finally move out of her sister’s basement because she’s employed again, or a worker who left his wife and child in China. The doc is unquestionably empathetic to the blue-collar workers, humanizing them through their struggles to make a better life. At the same time, it seems antagonistic about the personal motivations of upper management. Both the American executives and the Chinese executives who eventually replace them are shown making harsh and sometimes cruel decisions to protect the interest of the company. If American Factory isn’t overtly xenophobic toward Chinese culture, which is debatable, it probably has a beef with Chinese industry. Then again, would American executives be so different?

After premiering at the Sundance Film Festival in 2019, where Netflix acquired it, the film earned support from Michelle and Barack Obama’s Higher Ground Productions—a move bound to bring the film more exposure than it might have received without presidential approval. It’s the kind of film that doesn’t resign itself to a single thesis. Instead, it leaves you reeling from the complex, unresolvable cultural dynamics at play in our present and future globalization. And even though it would be easy to view the film as a story about what doesn’t work between American and Chinese industries, it contains sentiments that link the workers on the factory floor—all of them just human beings trying to make a wage to support their families. That’s at once a tender, human, and reductive view of the situation.

(Note: This review was selected by vote from supporters on Patreon.)

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review