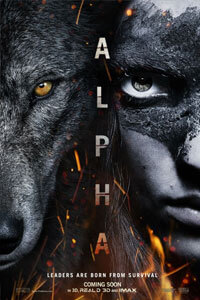

Alpha

By Brian Eggert |

Many theories about the evolution of the relationship between human and dog attempt to answer the question, who took the first step, people or the ancestral wolves that later became canines? Some argue that Homo sapiens domesticated wolves, seeking them out as pets and breeding only those tame enough to live among humans. Others believe that wolves, hungry for an easy meal, approached human camps and begged for scraps, and eventually, they learned how to behave around humans to survive. More recently, scientists have argued for coevolution, based on the mutual needs of both parties. The prehistoric adventure Alpha, which plays like the brainchild of Jean M. Auel and Jack London, demonstrates the latter theory. The spare, primordial tale of survival tells a familiar boy-and-his-dog story, except the film presents itself as the first such story in human history.

This ambitious concept comes from Albert Hughes, one half of the formerly named Hughes Brothers. Along with his brother Allen, Albert co-directed Menace II Society (1993), Dead Presidents (1995), and most recently The Book of Eli (2010)—their last film together. Since then, Allen has helmed the forgettable crime drama Broken City (2013), while Alpha marks the first solo project for Albert. If there’s a sense of sibling rivalry between the brothers, Allen should feel intimidated. Albert, who conceived the story on which the screenplay by Daniele Sebastian Wiedenhaupt was based, achieves something almost mythic with Alpha. Apart from opening titles that establish the settings as “Europe, 20,000 Years Ago,” the stripped-down narrative is accompanied by few words, and those are delivered in subtitles, translating a nonexistent prehistoric language conceived for the film.

In the opening sequence, a row of hunters crawls toward a herd of bison, and then, all at once, toss spears to create a wall that drives the stampede in the opposite direction, toward a cliff, where many fall to their deaths. During the fracas, the adolescent Keda (Kodi Smit-McPhee), on his first hunt beside his father, the brave chief (Jóhannes Haukur Jóhanneson), is thrown from the cliff, and he lands on a narrow ledge, unconscious. His clan presumes he’s dead. His father, heartbroken to have to leave the boy, wasn’t entirely convinced of Keda’s bravery. “He leads with his heart, not his spear,” explains his mother (Natassia Malthe) in a flashback. Left alone with a broken ankle, Keda, who resists killing, must face the sublimity of Nature to survive, and thus demonstrate his worthiness as the future brave leader of his people.

Early in his journey back home, Keda, who sustained a badly broken leg in his fall, is attacked by a pack of wolves and, while scampering up a tree to escape, he wounds one of them. Meeting the injured wolf with sympathy and patience, he rescues the animal and names it Alpha. After some initial growling and skittishness, the two heal together and learn to rely on one another for food, warmth, and protection. Alpha chases down wild hogs and other prey, guiding them toward Keda, who gradually learns that survival means killing. Sequences alternate between Alpha saving Keda’s life and vice versa, each time strengthening their bond. They face perilous weather conditions and dangerous predators, such as a pack of hyenas (yes, there were hyenas in Europe during the Ice Age) or various breeds of deadly big cats. Fortunately, Ray Romano, John Leguizamo, and Denis Leary do not lend their voices.

Hughes, collaborating with Austrian cinematographer Martin Gschlacht—who has worked almost exclusively on the European art film scene with titles like Revanche (2008) and Goodnight Mommy (2014)—realizes some marvelous and uncanny visuals throughout. The opening shots, for instance, recall the “Early Man” sequence from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), complete with majestic scenes of Nature contrasted by an unearthly, choral humming. Later, Hughes captures wistful moments with the aurora borealis or haunting dream sequences. However, since much of the film was shot in Canada and California, the landscapes and most of the animals are achieved with CGI, occasionally unconvincing. Smit-McPhee, who has been making the most of his rather unusual appearance in titles from The Road (2009) to his appearance as a young Nightcrawler in X-Men: Apocalypse (2016), commands the screen alongside his wolf companion, giving his most complete performance yet. Dog lovers will appreciate the measured pace at which Hughes builds their relationship, and the mostly CGI wolf proves to be a scene-stealer.

Finally released after several delays, Alpha is a hard sell. It’s original title, The Solutrean, didn’t help promotional efforts; neither did an investigation by American Humane into the deaths of some bison, resulting in their refusal to grant the picture their “No Animals Were Harmed” certification. Mainstream audiences attracted to a big-budget spectacle may resist the film’s subtitles, even though the basic boy-and-his-dog story doesn’t require much talking. But the grandeur and scope throughout, obvious computer animation notwithstanding, leaves the viewer with a sense of awe. Alpha is to be admired, familiar though the story may be, for its unconventionality and beauty. Not since Jean-Jacques Annaud, a clear influence here, tackled cave men in Quest for Fire (1981) and an animal’s perspective in The Bear (1988), has there been such an austere film about the basic connections between prehistoric people, animals, and Nature.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review