Allied

By Brian Eggert |

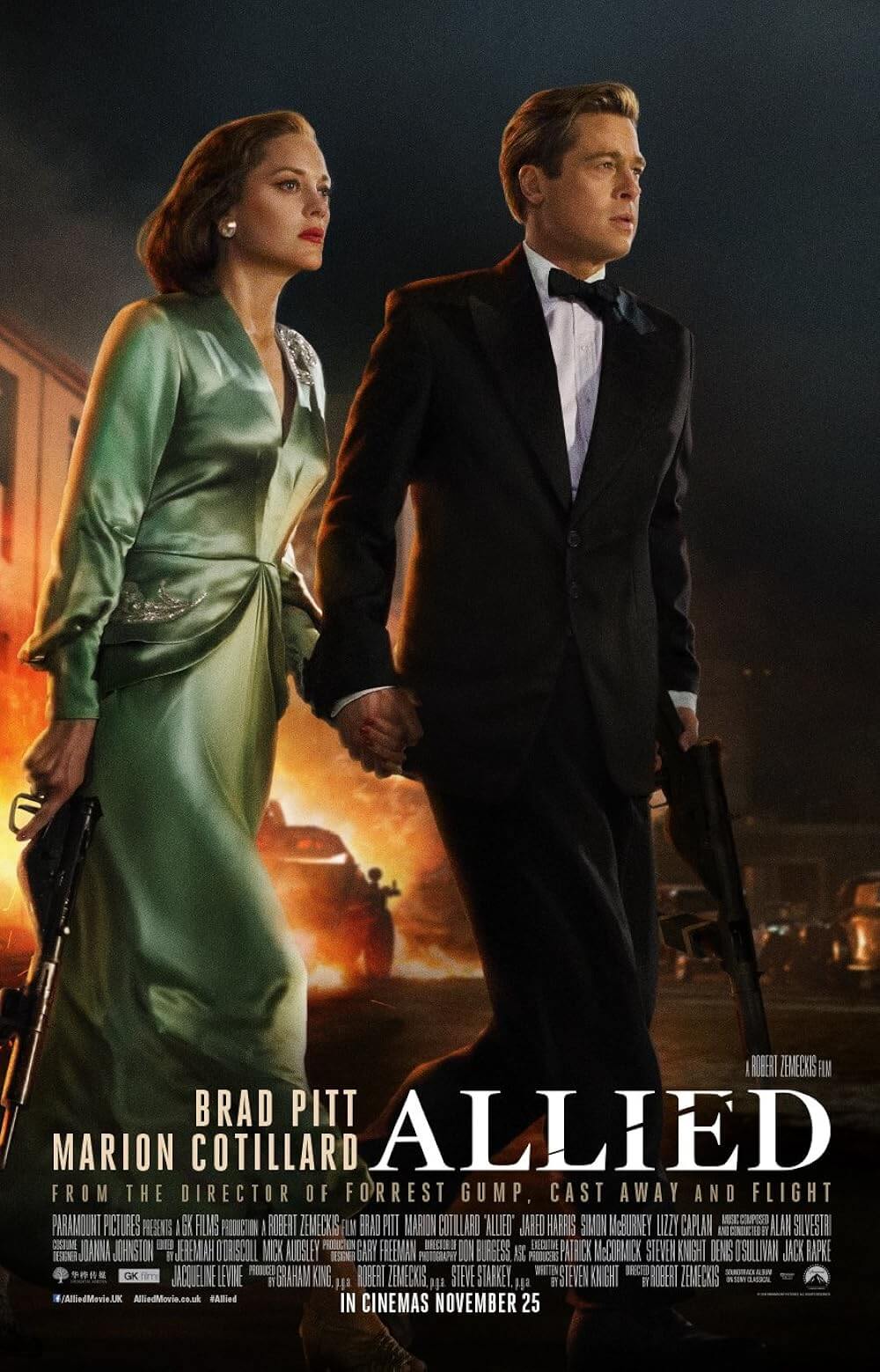

On the surface, Robert Zemeckis’ Allied may seem straightforward, a familiar sort of wartime romance whose tempo copies beats established in the Golden Age of Hollywood. At first, its politics seem certain and its moral principles firm, just like so many 1940s wartime classics. But similar to Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies from last year, Allied tells a story from the past through contemporary sensibilities. Although Zemeckis draws from classicized filmmakers like Michael Curtiz and Alfred Hitchcock for influence, Steven Knight’s intricate screenplay looks at the film’s World War II setting as a time of ambiguity and density, muddying otherwise clear divisions of patriotism and loyalty. Brad Pitt and Marion Cotillard bring elegant performances to an intelligent and stylish picture, which gradually reveals a profound emotional resonance under its outward restraint.

The film opens in 1942, as Canadian intelligence officer Max Vatan (Pitt) parachutes into the Moroccan desert. He arrives at a prearranged rendezvous in Casablanca to meet Marianne Beausejour (Cotillard), a French Resistance fighter posing as Vatan’s wife. She has been in Casablanca for weeks, establishing herself with the Vichy locals and German officials. Together, Max and Marianne intent to carry out an assassination of a German ambassador. Sharply dressed in costume designer Joanna Johnston’s elegant gowns and dapper suits, Cotillard and Pitt stand as one of the sexiest onscreen couples in recent memory, each delivering performances that rank among their best. Their initial interactions demonstrate her ability to charm the Vichy locals and his staid severity, while she plays the life of the party in public but critiques his Parisian accent as too Québécois in private. Nevertheless, the two fall in love while maintaining their cover, regardless of their otherwise detached professionalism, largely because of the fatalistic odds against either of them surviving the mission.

A year later, the story finds them together in London, married and parents to a newborn baby, ready to live happily ever after. Their characters soon face trouble when an SOE official (Simon McBurney) demands to see Max, and then warns there’s evidence suggesting the real Marianne was killed before Casablanca, and the woman with whom Max now lives is a German spy. The official explains they’re going to run a “Blue Dye” on Marianne, and just when a duller film would include expositional dialogue to explain what that means, Max interrupts and says he already knows how it works. They plan to leave out a piece of false intelligence, and if the information runs through a tapped German communiqué within a 72-hour window, then Marianne is guilty, and Max must kill her to demonstrate his loyalty. This is “standard operating procedure for intimate betrayal,” the official explains.

What are the possibilities? The SOE could have received inaccurate reports and, after 72 hours, Max will learn that his superiors unduly investigated his wife. Or maybe Marianne is, in fact, a spy for the Germans, and she’s so coldhearted and committed to her cause that getting married and having a baby with her enemy is nothing compared to her devotion to Hitler. At the same time, an outside chance remains that Max’s superiors have dreamt up this elaborate scheme to test his loyalties in consideration of an upcoming assignment. If so, then his behavior could spoil his chances at a promotion, and his new suspicion of Marianne is wholly unfounded. It seems as though only three possibilities could occur; however, the film always operates on an emotional level, regardless of the plot-centric setup. Indeed, nothing in Allied proves so simple or predictable. When finally the film reaches its conclusion, the audience could have never guessed the degree to which Zemeckis would avoid clichés and instead leave us devastated.

What are the possibilities? The SOE could have received inaccurate reports and, after 72 hours, Max will learn that his superiors unduly investigated his wife. Or maybe Marianne is, in fact, a spy for the Germans, and she’s so coldhearted and committed to her cause that getting married and having a baby with her enemy is nothing compared to her devotion to Hitler. At the same time, an outside chance remains that Max’s superiors have dreamt up this elaborate scheme to test his loyalties in consideration of an upcoming assignment. If so, then his behavior could spoil his chances at a promotion, and his new suspicion of Marianne is wholly unfounded. It seems as though only three possibilities could occur; however, the film always operates on an emotional level, regardless of the plot-centric setup. Indeed, nothing in Allied proves so simple or predictable. When finally the film reaches its conclusion, the audience could have never guessed the degree to which Zemeckis would avoid clichés and instead leave us devastated.

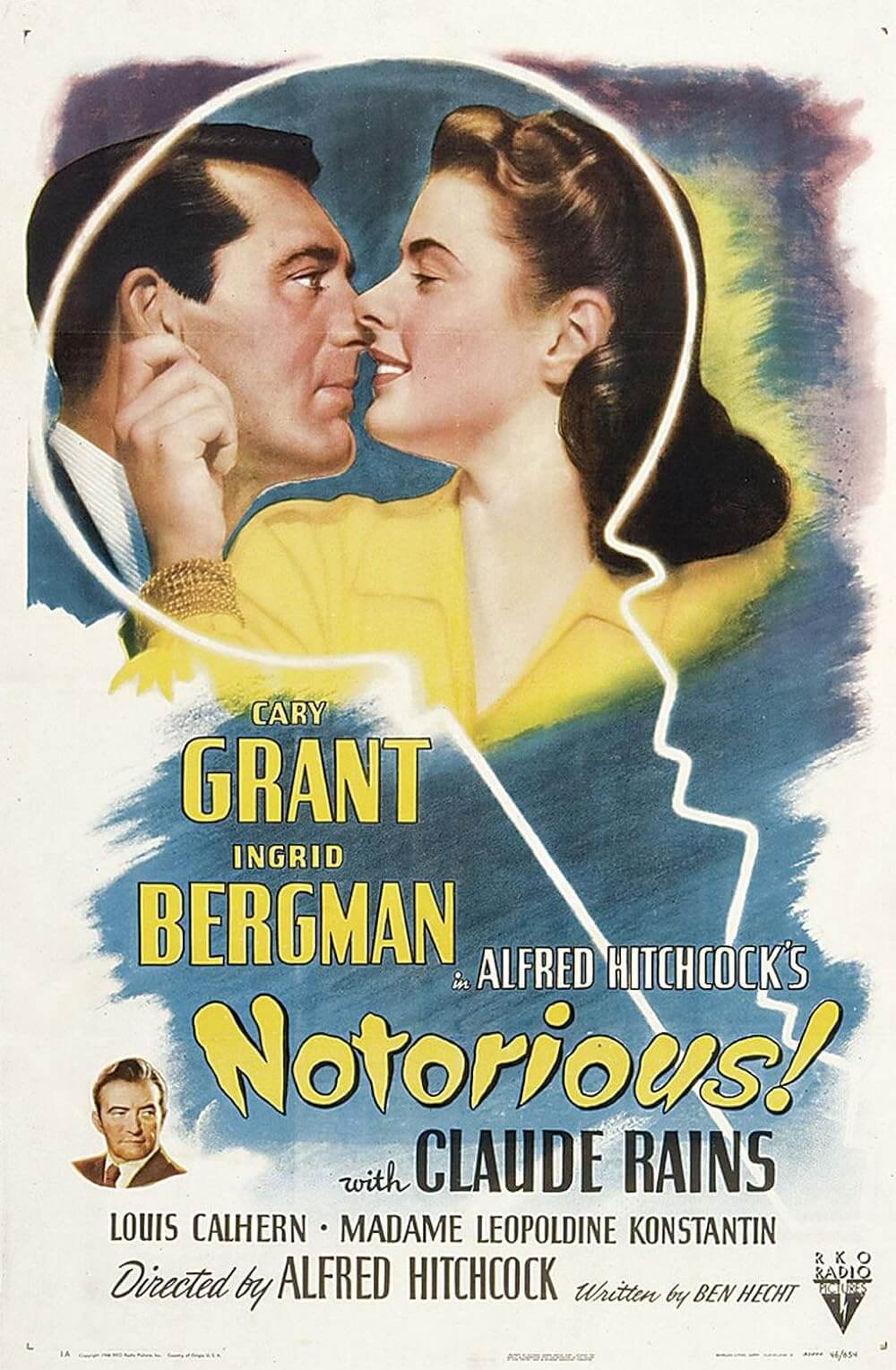

Much has already been written about the film’s similarities to Casablanca, Curtiz’s indelible classic from 1942. The opening act takes place in Casablanca, after all, and a performance of “La Marseillaise” figures heavily into the plot near the finale. Thematically, Casablanca and Allied both feature characters who must occupy secret roles in support of either their professional or personal lives. But more apt comparisons for Allied belong to several works by Hitchcock. In a way, the scenario recalls Hitchcock’s Suspicion (1941), in which Joan Fontaine suspected her husband, Cary Grant, to be a murderer. The uncertainty introduced into their intimate relationship was draining, until it turns out the film’s title was all too accurate. Perhaps Hitchcock’s greatest film is Notorious (1946), starring Grant and Ingrid Bergman, about a spy who sends his lover to investigate Nazis in Rio de Janeiro, putting distrust and an incredible strain on their relationship.

Suffice it to say, Allied has roots in old-fashioned storytelling, although it takes a decidedly realistic perspective in its depiction of wartime behavior. Rather than typical gung-ho, duty-bound soldiers and spies, we see London under the threat of devastation and the resulting effect that has on its culture. Max’s sister (Lizzy Caplan) openly engages in a lesbian relationship in front of her unbothered military superiors; later, Max and Marianne throw a wild party where cocaine seems just as normal as public sex. When the Nazis are at your doorstep, certain measures of decorum simply lose their importance. Such details offer a portrait of WWII culture unlike anything to which audiences are accustomed outside of a few rare exceptions, such as Paul Verhoeven’s Black Book (2007), which may be Allied’s closest cinematic sibling. Knight has researched the reality of his chosen era and delivered another scathing portrait of London to rival his screenplays for Dirty Pretty Things (2003) and Eastern Promises (2007).

Some critics have questioned Pitt’s subdued presence and censured him for being stoic and unemotive. However, his performance recalls that of Lino Ventura in Jean-Pierre Melville’s Army of Shadows (1969), the greatest of all films about the French Resistance and an essential picture to understand the spy sensibility. Ventura has flat, tired features throughout that film; there’s nary an expression on his face, and every line of dialogue is loaded. Melville, who served in the Resistance during the war, understood how maintaining that level of secrecy and inward control meant stripping away your sense of self and adopting an altogether committed state of mind. Performing as a spy who has a similar discipline, Pitt may not engage in expressive acting or charm his audience with his smile, but he captures the spy state of mind that Hollywood very often disregards in favor of large, easily relatable emotions.

Allied is far more complicated than standard Hollywood fare, in that its passions have layers of loyalty and duty embedded beneath the surface—and the audience feels turned in knots while trying to determine where Marianne’s loyalties reside. As dispassionate as the film may seem early on, watching requires the viewer to place themselves in the spy mindset and understand that what is shown is superficial. Max and Marianne behave in ways so that their intentions and true feelings can and should be questioned by the audience. And as their relationship grows throughout the picture, the suspicion grows with it, and suddenly the film begins to share much more in common with suspenseful tragedy rather than a purely romantic wartime drama. To be sure, Allied may have been inspired by the classics, but it remains something altogether unique and infinitely more serious than most viewers will expect.

Allied is far more complicated than standard Hollywood fare, in that its passions have layers of loyalty and duty embedded beneath the surface—and the audience feels turned in knots while trying to determine where Marianne’s loyalties reside. As dispassionate as the film may seem early on, watching requires the viewer to place themselves in the spy mindset and understand that what is shown is superficial. Max and Marianne behave in ways so that their intentions and true feelings can and should be questioned by the audience. And as their relationship grows throughout the picture, the suspicion grows with it, and suddenly the film begins to share much more in common with suspenseful tragedy rather than a purely romantic wartime drama. To be sure, Allied may have been inspired by the classics, but it remains something altogether unique and infinitely more serious than most viewers will expect.

On a formal level, cinematographer Don Burgess puts forth a clean and classy visual presentation, while the editing team (Mick Audsley and Jeremiah O’Driscoll) delivers seamless and invisible cuts amid some creative transitions. In addition to his polished production, Zemeckis, ever the Hollywood technophile, cannot resist incorporating a few dazzling sequences of showmanship into the picture. A love scene in the Moroccan desert in which the camera spins around Max and Marianne in a sand-beaten car recalls the intimacy from a similar scene in The English Patient (1997). Later, Zemeckis thrills us with a fast-paced assassination mission and the birth of Marianne’s child during a bombing in London. Although the air raid scenes are rendered with CGI, they contain incredible detail, such as when one of the damaged planes takes a sudden turn and crashes near Max and Marianne’s home.

Zemeckis’ visual touches never supplant the power of his film’s spy suspense, central love story, or subsequent paranoia, leaving Allied to feel, in the end, a terrifically executed picture in each of its various strains. Much like Zemeckis’ 2012 release Flight, the basic setup seems straightforward, until the story veers in several directions the viewer never anticipated. At the same time, every aspect of the picture hits its mark, from the expert performances to Alan Silvestri’s intimate score to the pristine quality of Zemeckis’ technical flourishes. What remains most impressive are the psychological intricacies of Max and Marianne, their world, and the extent to which Allied is less an escapist piece of wartime fantasy than a tragic romance set in a tumultuous, unpredictable time in history. Although the film may seem deceptively old-fashioned and entrenched in classic films, the storytelling feels relevant and modern.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review