All Is Lost

By Brian Eggert |

Films about absolute solitude rarely, if ever, occur. Long periods of seclusion in cinema are usually broken with the illusion of company and vast amounts of internal dialogue. Sandra Bullock had George Clooney (real or imagined) in her adrift-in-space thriller Gravity; Suraj Sharma interacted with his Bengal tiger Richard Parker (again, real or imagined) in Life of Pi; Tom Hanks talked to his imaginary soccer ball friend Wilson in Cast Away. Each projection of the stranded protagonist’s mind serves a purpose, not only to figuratively represent some basic need in the character’s psyche to interrupt their own loneliness but also to give the main character someone with whom they can speak, if only for the sake of the audience. Real or not, watching a character interact or mutter exchanges with another entity (be it a person, animal, or thing) is easier than watching a human being willingly accept their own isolation with calm silence. By its very nature, solitude is uncinematic.

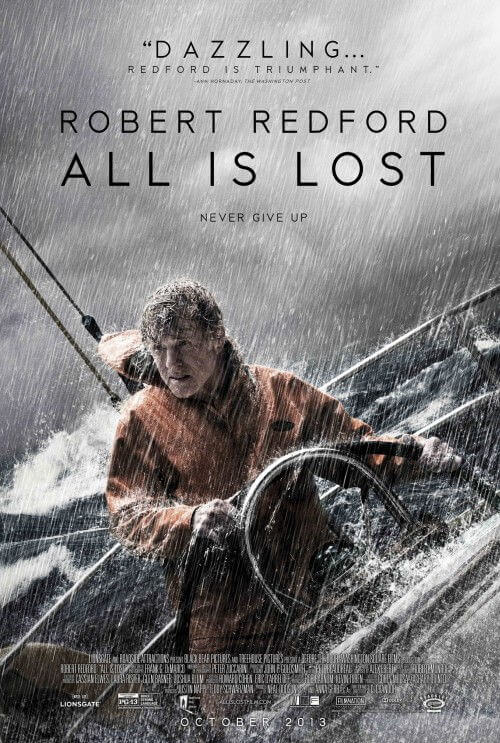

With All Is Lost, writer-director J.C. Chandor proves this truism false. He enlivens silence and solitude through action as a Silent Era filmmaker might. And moreover, he makes an incredible leap from his timely, dialogue-driven, Oscar-nominated Wall Street drama Margin Call to a seafaring survival story with just a few spoken lines. Channeling Hemingway’s Old Man and the Sea in a classic tale of Man vs. Nature, Chandor’s film follows an unnamed sailor (dubbed “Our Man” in the end credits), played by Robert Redford. We know almost nothing about this character, save for what we gather from his brief lines in the opening narration. Presumably to his wife and children, he reads aloud a final note in which he professes “I’m sorry,” and then maintains, “I fought to the end.” After these words, he barely speaks, never talking to himself or projecting his lonesomeness onto something that’s never there.

Our Man sails alone on a yacht through the Indian Ocean. He seems to be intelligent and well-off, someone who can afford to take his own vessel halfway across the world, and yet he remains smart enough to carry out a solo expedition. He’s awakened by a crashing impact and the sound of water flooding his cabin and destroying his electronic equipment. Upon inspection, his boat has run into a metal container floating in the ocean that’s apparently fallen from a cargo ship. He repairs the hole as best he can, and as he attempts to hoist himself up on his mast to patch up his electronics, he sees a massive storm approaching in the distance. Huge waves roll his boat over, and inside he spins like clothes in a dryer; when it’s over, he’s left with a gash on his forehead and no choice but to abandon his ship for a life raft. With limited supplies and a book on celestial navigation to guide him, our resourceful survivor attempts to make it North to Indonesian shipping lanes in hopes of rescue.

At 77, Redford has aged well. Though he’s no longer the heartthrob from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid or All the President’s Men, he carries a dignity and undeniable command of the screen. Redford’s performance is completely un-self-conscious, fuelled by his naturalism and underplayed mannerisms. His character approaches each problem before him without losing himself in emotion or panic, relying on his thoughtful examination of what needs to be done. It’s perceptible that under the surface, he realizes the full extent of his predicament, but he’s too wise to lose his nerve. Redford appears leathery and weathered by time, which provides his character with the visible experience he needs to survive. And Our Man’s perseverance gives way in just one instance where, for a moment, he loses hope, and in that brief flash, trembles with frustration and shouts an expletive the audience has been uttering to themselves quietly throughout the entire film thus far. This brief respite from Redford’s otherwise calm, thinking character is a revelation.

Chandor has constructed an impressive production. On a technical level, he and cinematographer Frank G. DeMarco use a combination of location footage and green screens. The film was shot around the Bahamas but the director integrates live-action environments with vast CGI storms for a wholly believable and engrossing visual experience. Ever since Steven Spielberg’s legendarily troubled experience making Jaws, water shoots have been dreaded by filmmakers, but computer-animated special FX no doubt eased Chandor’s production from being plagued by the usual trials of filming on the ocean. The director certainly relishes his quiet, sometimes frightening shots of CGI fish and sharks swimming under Our Man’s raft. Filmed for just $9 million, the production looks far more expensive and never once hints at its relatively low-budget, independent film roots. Meanwhile, DeMarco’s tight camerawork keeps us involved in Redford’s every action, and the editing by Pete Beaudreau is economical and never resorts to abrupt cutting to artificially enhance the film’s energy.

Best of all, unlike other films about stranded survivors, All Is Lost doesn’t attempt to poeticize Our Man’s fight for survival into the character’s personal allegory through which he resolves his existential issues. Just recently, the visual wonder of Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity was somewhat spoiled by the narrative’s symbolic flourishes and attempts to bring “meaning” to the thrills. And while Chandor’s film avoids such symbolic grandstanding, its arguable lack of metaphoric purpose could also be seen as a dramatic fault. The film strips away the usual emotional frills of a Man vs. Nature conflict and approaches the story with deep restraint and narrative simplicity. As a result, Redford’s outstandingly composed performance is crucial to the film’s success; and it’s not difficult to imagine another version of Chandor’s film without Redford that completely fails because its lead doesn’t carry the same presence. For all its discipline, All is Lost is a commendable and engaging motion picture, but also a rare achievement in spare filmmaking.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review