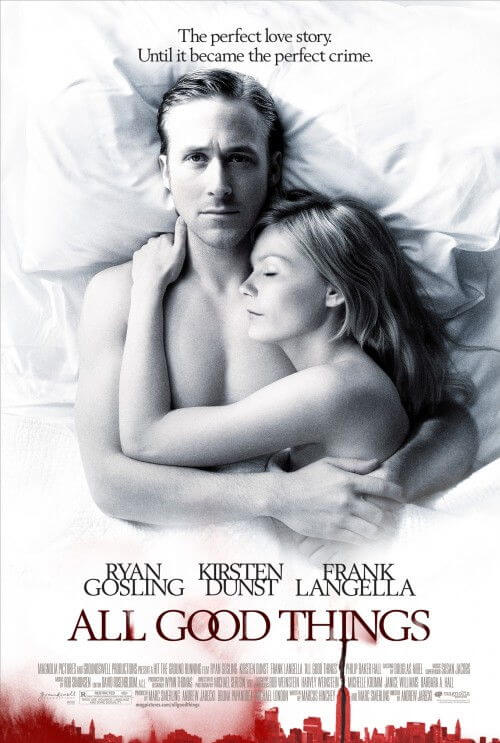

All Good Things

By Brian Eggert |

In what could be called speculative true crime fiction, All Good Things considers the actual unsolved murder case surrounding Robert Durst and attempts to fill in the blanks. The film arrives two years after its completion in 2008, receiving a truncated release by Magnolia, vis-à-vis The Weinstein Company, in arthouse theaters and video-on-demand. Director Andrew Jarecki, best known for his documentary Capturing the Friedmans, dramatizes actual events and engages in pure conjecture to give audiences closure that the real story doesn’t offer, suggesting some unsettling, out-of-left-field conclusions. But the vague way in which Jarecki and his screenwriters, Marcus Hinchey and Marc Smerling, reach their hypotheses about what “really happened” feels less engaging than a documentary on the same subject might’ve been.

On understandable legal grounds, actual names have been changed in the story to protect those involved, but news coverage of Durst’s case confirms that the filmmakers stuck close to the actual events, yet dwelled on circumstantial evidence. Robert Durst’s name was changed to David Marks, played by Ryan Gosling. Kathleen McCormack, Durst’s wife who mysteriously disappeared in 1982, is renamed Katie McCarthy, played by Kirsten Dunst. In the early 1970s, David and Katie meet and quickly marry, he from a wealthy New York City family of real-estate developers and she from a sweet middle-class homestead. They open a health food store in the Vermont countryside, enjoying a simple and quiet life, until David’s father, Sanford (Frank Langella), insists that he return to the city to pursue the family business, based in purveying stripteases and porn shops in Times Square. But when they uproot and move into the city, David’s resentment for, and extensive “issues” with his family begins to emerge.

Apparent psychological problems show in David’s mumbling to himself, his heavy blinking, or when his past is referenced. As a child, he witnessed his mother commit suicide, after which psychologists determined he would surely be unstable. Naïve to these truths, Katie finally begins to notice how David rails against his father yet cannot disobey him; and when she becomes pregnant, David forces her to abort the child out of his disdain for fatherhood. Soon he becomes violent and abusive toward Katie, who attempts to escape the marriage but cannot due to the Marks’ safeguards against anyone leaving the family. As the tale grows more desperate, Jarecki makes foggy allusions to murder, reveals David’s penchant for cross-dressing, and cuts away to inexplicable scenes of a woman dumping bags off a bridge. The story takes place over several decades, ending in the ‘00s with an awkward third act. But the pieces of the puzzle are left for us to put together from a rather unsatisfying structure, told via flashback from a court case in 2003.

Gosling’s upturned eyes and withdrawn onscreen presence describe a pained, baffling characterization, not unlike his turn in Lars and the Real Girl, except that that film knew enough to give audiences some tangible answers as to the motives of the main character. It’s an empty performance that we neither like nor despise, since Jarecki tiptoes around to avoid making too much of a declaration about David’s guilt. Dunst does a fine job capturing the wholesome innocence corrupted by cocaine and spousal abuse, but her performance won’t turn any critical heads. And Langella aptly plays the epitome of corruption whose past becomes just as mysterious as his son’s when David, after supposedly murdering his wife, tells him, rather cryptically, how they’re “the same” now.

Whether it’s Gosling’s vacant performance, the non-linear structure, or simply not knowing that distances the viewer, All Good Things is an unsatisfying experience. In a way, it recalls David Fincher’s underrated Zodiac, both being about unsolved cases. But where Fincher’s film asked questions and cleverly obsessed over not knowing, in turn making The Unknown the theme of his film, Jarecki allows a dramatic reenactment to play out and forgets to tender a necessary sense of closure to his melodrama. Given the incompleteness of his dramatic structure, Jarecki would have done better to put his enthusiasm for an admittedly intriguing real-life case into another documentary—a format where questions are often raised yet go unanswered.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review