Alien vs. Predator

By Brian Eggert |

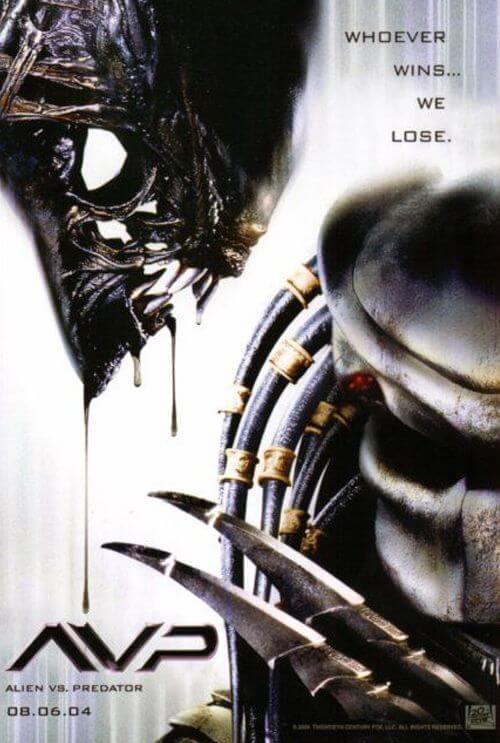

With its franchise on life support, the Alien movies have worsened in their progression, sustaining none of the momentum created by Ridley Scott and James Cameron’s initial entries. The series was knocked around with Alien 3 and hospitalized with Alien: Resurrection. And then there’s the Predator franchise, which had one healthy child and a second, sickly one; the former was a solid Arnold Schwarzenegger action movie, and the latter featured Gary Busey in a performance scarier than a xenomorph. After seeing Alien vs. Predator (dubbed AVP by 20th Century Fox marketing), I really think Fox should consider pulling the plug on both.

The studio took a cue from the popular video games where the Alien and Predator face off, and from comic books where the movie monsters battle against the likes of Batman or Superman. The aliens’ eventual meeting should come as no surprise to moviegoers; in Predator 2, in the hunter’s spaceship, we see a xenomorph skull displayed on the trophy board. Ever since that image, fans of both franchises have clamored for a movie on the subject. I was not one of them. I see no potential in watching movie monsters duke it out since the concept rarely offers sympathetic human characters (see Freddy vs. Jason for a similar example).

AVP was written and directed by Paul W.S. Anderson, the anti-genius behind Mortal Kombat and the Resident Evil franchise. His brand of big-on-action and small-on-story turns high box-office numbers but also turns my stomach. Reliant on CGI-heavy effects and perfunctory slow-motion action scenes, Anderson’s movies play out no differently than the games on which they’re based. His characters are as thin as tissue paper, and his writing is filled with silly dialogue. Here, Anderson starts us out with a wealthy independent mogul’s satellite discovering a heat signature buried under thousands of feet of Antarctic ice. Thanks to 3-D underground imagining, curiously familiar to that used in Resident Evil, we see a pyramid buried under the ice (more on that later). Said mogul, named Charles Bishop Weyland, is played by Lance Henriksen, better known as the “artificial person” Bishop in Aliens and Alien 3. Don’t expect to learn Bishop’s android origins in AVP; he’s just here as a familiar face, or perhaps to indicate the eventual appearance of the corrupt Weyland-Yutani Corporation in the Alien series.

Rushing to compile a crack team of specialty scientists, Weyland enlists the rough terrain adventurer Alexa (Sanaa Lathan) as the team’s guide, failed archeologist Sebastian (Raoul Bova) to identify the structure, and goofy chemist Graeme (Ewen Bremmer) to date it. This is a body-count movie—a picture driven by killing everyone onscreen in new and inventive ways—so there’s also the usual selection of anonymous personnel to become Alien hosts and, of course, military types with big guns to blast them away.

We arrive at an Antarctic whaling station where, in the film’s prologue, set in 1904, we see Predators hunting whalers for sport (at least the Predators have their ethics in the right place). One hundred years later, when Weyland’s team arrives, not much has changed with the place. Now, you’d think that being in Antarctica and unmanned for 100 years that the whaling camp might have weathered away. Alas, there’s a meager six inches of snowy fluff over everything but not much damage otherwise. I’m shocked by this because Anderson seemed so preoccupied with Antarctica-based trivia when writing the script. The first ten minutes of AVP are comprised of dialogue where Alexa instructs the others on the risky climate, how fast the freezing water will kill you, and what the Point of Safe Return is—all pointlessly interesting facts that hold no bearing on the subsequent alien war. The Antarctic setting is more of a way for Anderson to infuse the movie with illogical twists on established horror movie tropes (for example, the traditional false-alarm cat is replaced by a penguin).

Now, about that pyramid. When Weyland’s team gets through the ice and down into the structure, they discover it was built with a combination of ancient Egyptian, Aztec, and Cambodian architectural and hieroglyphic characteristics. We learn that all of human civilization came about as a result of the Predator race, which visited Earth thousands upon thousands of years ago, taught us, primitives, to build, and then used our pyramids as enclosed hunting grounds. Every one hundred years, Predators return to hunt Aliens for sport. If the Predators lose, they set off a bomb to wipe out the encroaching Alien threat, hence explaining the disappearances of the Mayan and Anasazi peoples. (Thank you for the history lesson, Mr. Anderson.)

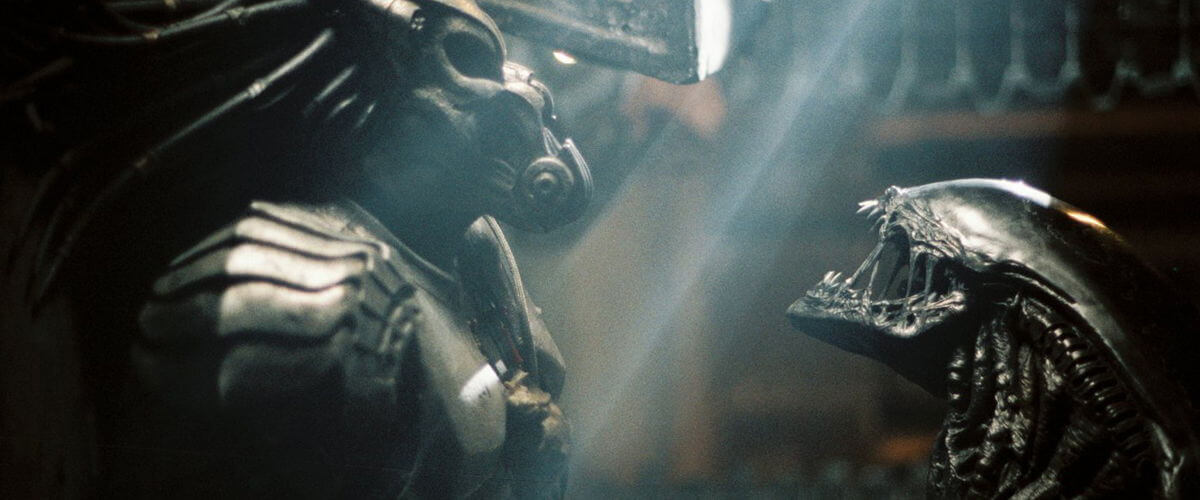

Alexa and her team set off triggers that spark the reanimation of a dormant Alien Queen, strapped in and penetrated with electrodes and such, coming to life like Frankenstein. She begins laying eggs, humans get face-hugged, Aliens burst from chest cavities, and the hunt begins. The ambiguous human characters get caught in a fight between ambiguous monsters, fighting an unintelligibly shot mess of ambiguous CGI warfare.

Following the decline of the Alien franchise, here the Aliens growl and sound suspiciously like Jurassic Park dinosaurs. Remember in Ridley Scott’s Alien, when Ripley and the creature were alone on the escape shuttle; the Alien releases a throaty hiss ever-so-quietly, never screeching or roaring out like the silly monsters in this picture. The sequels have dissolved any fear for these archetypal movie monsters by revealing them entirely, bringing them out of the dark, and making them disposable video game villains. One dies, another one pops up, and who cares because they’re not frightening anymore.

This movie isn’t scary or particularly thrilling. There are no strong human characters (like Ripley) to link to (a requirement of movies featuring a variety of non-speaking aliens). Neither the Alien nor Predator franchises evolve or regain any of the lost ground they need to recoup—rather the opposite. The movie is a full-fledged geek-a-thon, appealing only to those few who got a kick out of the video games and poor, monster-laden comic books. Fox likely hoped AVP would consume its budget back in the first week or so of release; just enough effort was exerted to produce a curiosity-inducing trailer and get some teens into cinemas (Fox demanded a PG-13 rating, as opposed to the traditional R-rating for individual Alien and Predator movies, for this reason). Their plan was a financial success, despite making an unforgivably stupid movie. Hence the sequel: Alien vs. Predator: Requiem.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review