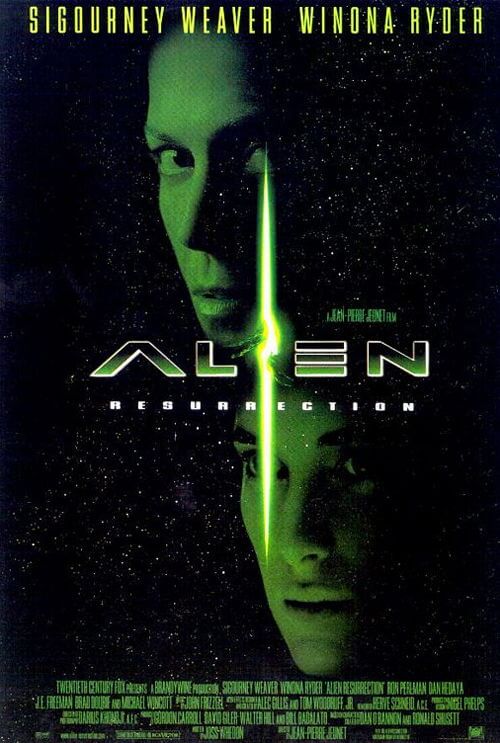

Alien: Resurrection

By Brian Eggert |

There’s not much to say about Alien: Resurrection, except to point out the many ways in which this movie is a disaster. When compared to its predecessors, everything about the experience is irksome. The actors are miscast and deliver silly, over-the-top performances. The aliens themselves growl and roar instead of hiss. Even Sigourney Weaver’s Ellen Ripley is not the character we’ve come to love since the original Alien. Rather, she’s a cocky superhero who moves like an alien herself. Nothing feels right. French director Jean-Pierre Jeunet, whose fabulist and eccentric The City of Lost Children (1995) earned him the job, has no apparent interest in staying true to the series. It’s as though Jeunet never bothered watching what came before, and so his movie feels in no way related. Of course, every director in the Alien franchise has put his personal stamp on his respective film, and certainly, this movie feels like a Jeunet production through and through. But in spite of his attempts to differentiate his movie from the first, this 1997 sequel put the first major nail in the franchise’s casket, artistically speaking.

Hoping to continue the Alien saga despite—or perhaps because of—the disappointing reception of Alien 3 (a film that was supposed to end the series with Ripley’s death), 20th Century Fox hired screenwriter Joss Whedon to somehow revive Ripley and press on. Whedon, whose script for Buffy the Vampire Slayer and doctoring of Speed and Waterworld garnered him some attention, proceeded with a cloning concept backed by Brandywine producers David Giler and Walter Hill. Whedon’s script contained signature ideas to those familiar with his later work (Firefly showrunner, writer-director of The Avengers), including a gang of space pirates and a comic-booky tone. True to the series was a corporate conspiracy bent on weaponizing the xenomorph species. Although, Whedon’s script notes that Weyland-Yutani, the evil corporation from the first three films, has since been bought out by “Wal-Mart” and replaced by an independent military science installation, the Auriga, headed by the maniacal Dr. Wren (J. E. Freeman) and corrupt General Perez (Dan Hedaya).

The story takes place some 200 years after Ripley’s sacrificial leap into the lead fire in the finale of Alien 3. Using blood samples found in the prison on Fury 161, scientists have attempted to separate and isolate Ripley’s DNA from the alien Queen that was inside her. After many botched attempts, they’ve managed to engineer a whole Ripley and a complete Queen alien on their space station. Except, Ripley still has traces of the alien DNA inside her, making her somehow stronger, faster, and more aggressive. Her behavior becomes almost primal, and her blood has acidic qualities like that of a xenomorph. Meanwhile, the scientists have contracted a ragtag band of space pirates to hijack hypersleep pods, and these poor cryogenically frozen people will serve as hosts to Facehuggers and spawn alien specimens. Soon after the pirate ship named Betty, captained by Frank Elgyn (Michael Wincott), arrives at the station, the newest of her crew named Call (Winona Ryder), exposes the military’s plot to engineer aliens. All at once, the aliens escape captivity and wreak havoc, causing the installation’s emergency protocol to take over and return everyone to Earth. With a small window to save Earth from alien infestation, the space pirates, a few remaining military personnel, and the newly super-powered Ripley make their way through the station to escape.

Along the way, the filmmakers subject their audience to a procession of neat ideas that serve little narrative purpose. Ripley taunts gruff pirate Johner (Ron Perlman) on a rec-room basketball court and then makes a long-distance swish with her back turned. A demented scientist (Brad Dourif) identifies with the aliens; he finds them beauuuuuutiful, and has a clever little exchange with one on the other side of protective glass. An underwater chase boasting cartoony CGI aliens stands as the movie’s best sequence. It leads to an opening in the water covered by a hardened layer of alien slime, on the other side of which are eggs waiting to hatch. An alien thrusts its double-jaw into the back of General Perez’s head; the back of his head gone, Perez reaches back there and pulls out a chunk of his brains and gives a You gotta be kiddin’ me look before he dies. Later, one of the alien hosts (Leland Orser) feels the alien inside him is about to burst; he uses this opportunity to hold Dr. Wren’s head against his chest, where the chestburster explodes not only through the host’s chest but Wren’s head. In an altogether hollow twist, Call reveals she’s a robot. Each of these ideas is more nonsensical and pointless than the last, conceived only because they might look cool onscreen, not because they intensify the suspense, immerse the audience in the proceedings, or deepen the characters.

Like these isolated moments strung together in Whedon’s screenplay, his characters are equally manufactured: a robot, a sharpshooter, a wheelchair-bound nice guy, a hardened captain, a dim-witted toughguy, and so on. Some might argue that Ripley’s character is dynamic compared to Weaver’s heroine from the earlier films; admittedly, her role has two dimensions instead of the one-dimensional level at which every other character in this movie operates. As they race to escape to the Betty, the survivors find a room with the botched attempts to engineer Ripley; a series of alien-Ripley hybrids are stored in formaldehyde, but one still lives and beckons to Ripley, “Kill me!” She sets the room ablaze in tears. Weaver co-produced Alien: Resurrection and secured herself an $11 million payday, but her acting has never been worse. Weaver’s talent is considerable and diverse, yet her performance here consists of moody glares unbalanced by cornball one-liners. When Johner (who finds a way to incorporate “man” into every line) confirms with Ripley that she’s dealt with xenomorphs before, he asks, “Wow, man. So, like, what did you do?” She replies with a tongue-in-cheek smile, “I died.” Later, a soldier recognizes her and says, “I thought you were dead.” Another brash grin, “Yeah, I get that a lot.” This isn’t acting; it’s reading lines with the self-satisfaction that you’re being overpaid for your efforts.

Like these isolated moments strung together in Whedon’s screenplay, his characters are equally manufactured: a robot, a sharpshooter, a wheelchair-bound nice guy, a hardened captain, a dim-witted toughguy, and so on. Some might argue that Ripley’s character is dynamic compared to Weaver’s heroine from the earlier films; admittedly, her role has two dimensions instead of the one-dimensional level at which every other character in this movie operates. As they race to escape to the Betty, the survivors find a room with the botched attempts to engineer Ripley; a series of alien-Ripley hybrids are stored in formaldehyde, but one still lives and beckons to Ripley, “Kill me!” She sets the room ablaze in tears. Weaver co-produced Alien: Resurrection and secured herself an $11 million payday, but her acting has never been worse. Weaver’s talent is considerable and diverse, yet her performance here consists of moody glares unbalanced by cornball one-liners. When Johner (who finds a way to incorporate “man” into every line) confirms with Ripley that she’s dealt with xenomorphs before, he asks, “Wow, man. So, like, what did you do?” She replies with a tongue-in-cheek smile, “I died.” Later, a soldier recognizes her and says, “I thought you were dead.” Another brash grin, “Yeah, I get that a lot.” This isn’t acting; it’s reading lines with the self-satisfaction that you’re being overpaid for your efforts.

More absurd is Ripley’s lingering connection with the aliens and what it leads to in the story. With traces of alien DNA in her system, she seems to communicate with them on some level. She comes to feel a kinship with them. She’s soon captured and carted off to the Queen’s lair, where, instead of the iconic ovipositor from Aliens, the Queen gives birth from a womb to an alien-human hybrid, which seems to have emotions relative to Frankenstein’s monster—it wants a friend and Ripley as a mother just as much as it wants to destroy everything in its path. With human-like skin, an elongated head, sad and expressive eyes, a twitching nose, and a gangly body, the design results in a creature that moves slowly and screeches loudly. It’s an unintentionally funny-looking thing, grossly un-scary, and memorable only for how ridiculous it manages to appear. Despite its labored movements, the hybrid somehow manages to beat the Betty crew back to their ship, where in the final battle, it’s sucked out into the vacuum of space through a tiny crack in the ship’s aperture; this moment is both excruciatingly violent and cathartic for audiences who wanted the silly hybrid to disappear from the screen and their memories forevermore.

Whedon’s script and Jeunet’s ostentatious style force a stimulus overload. There’s simply too much going on here, and none of it feels sufficiently explored or tonally appropriate for the series. Of course, the 200-year gap between films allows the production an excuse to separate itself. But at the same time, a certain level of cohesion is expected. It’s not that Jeunet and Whedon were lazy or weren’t trying for something unique; rather, their efforts were so monumentally misguided that nothing about the movie works. Jeunet’s deliberately wacky angles and inappropriate kitsch sour any hope of seriousness. The tone shifts from lighthearted banter to over-the-top gore, and there’s no end of clichéd dialogue to distance us from the characters. Whedon later claimed the director and actors misunderstood his script, and the production approached the material in the wrong way, but Whedon’s usual sense of humor is evident nonetheless, and it couldn’t be more unsuitable for this series. Moreover, Jeunet’s stylistic flourishes always seem to be winking at the audience, who in previous entries were submerged in a science-fiction horror presentation instead of the uneven action-comedy this movie proves to be.

Made for $70 million and earning more than $160 million in worldwide receipts, Alien: Resurrection earned a profit for 20th Century Fox. Nevertheless, it proved the least successful addition to the franchise at that point. Subsequent efforts on Weaver’s part to develop a fifth entry featuring Ripley, with the original’s director Ridley Scott at the helm, disappeared after the studio had lost interest. The Alien series would become the stuff of video games and action figures, and the days of artistic credibility had long since passed. In some ways, Jeunet and Whedon made a worse movie than the abysmal Alien vs. Predator movies to follow, because at least those movies’ creative ambitions were low, making the outcome decidedly less offensive. Alien: Resurrection has lofty objectives and achieves none of them with its lack of nuance, substance, and restraint. For devoted fans, it’s an abomination that, like its central monster, deserves to be sucked out into space from a tiny opening and forgotten for all time.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review