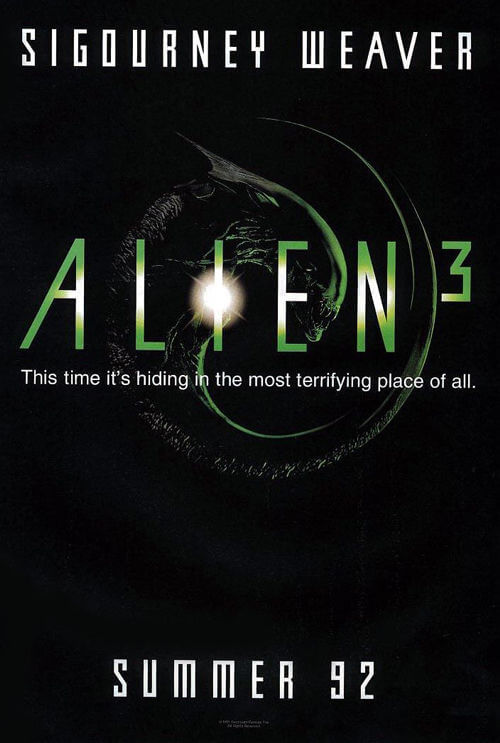

Alien 3

By Brian Eggert |

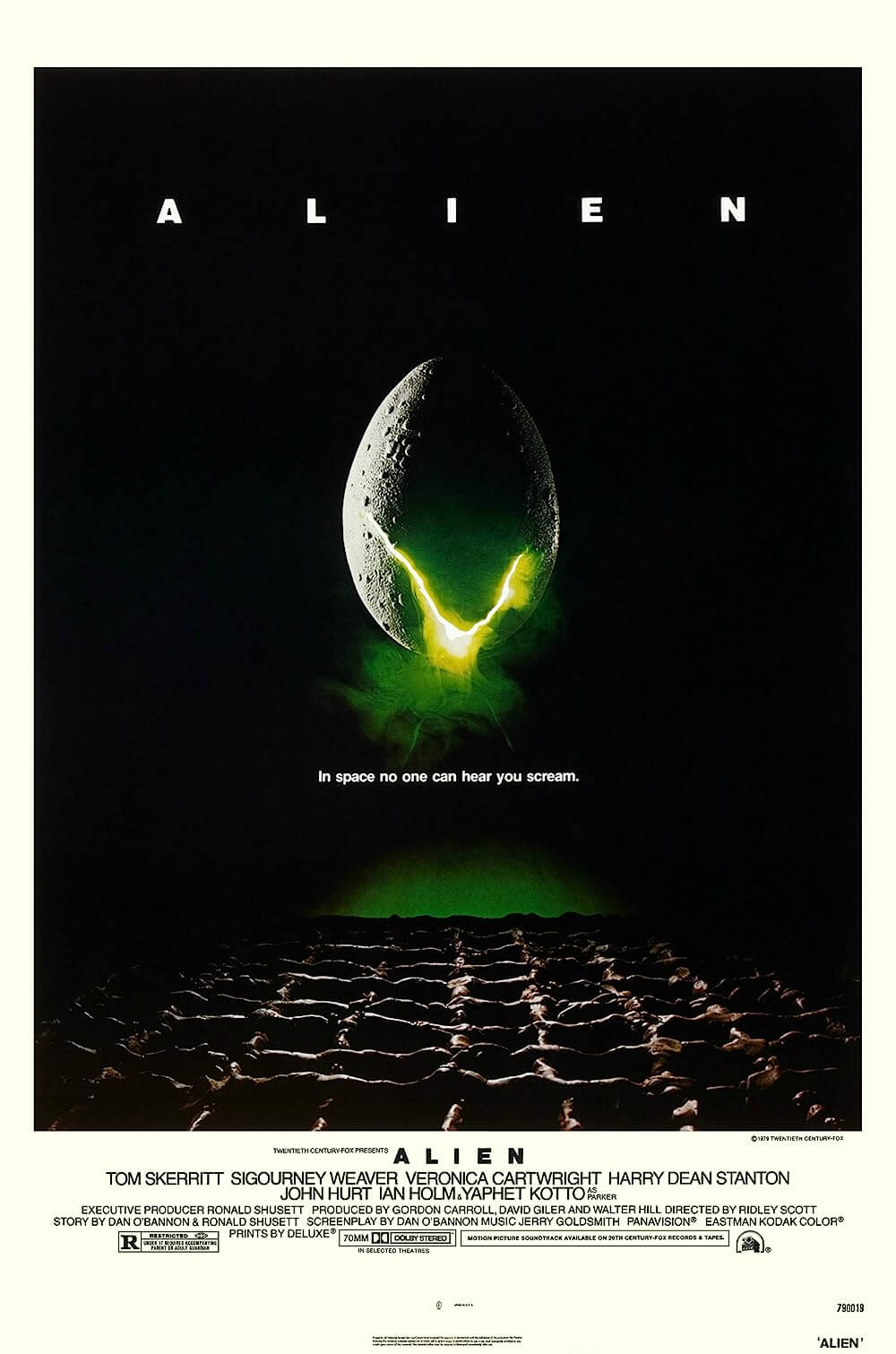

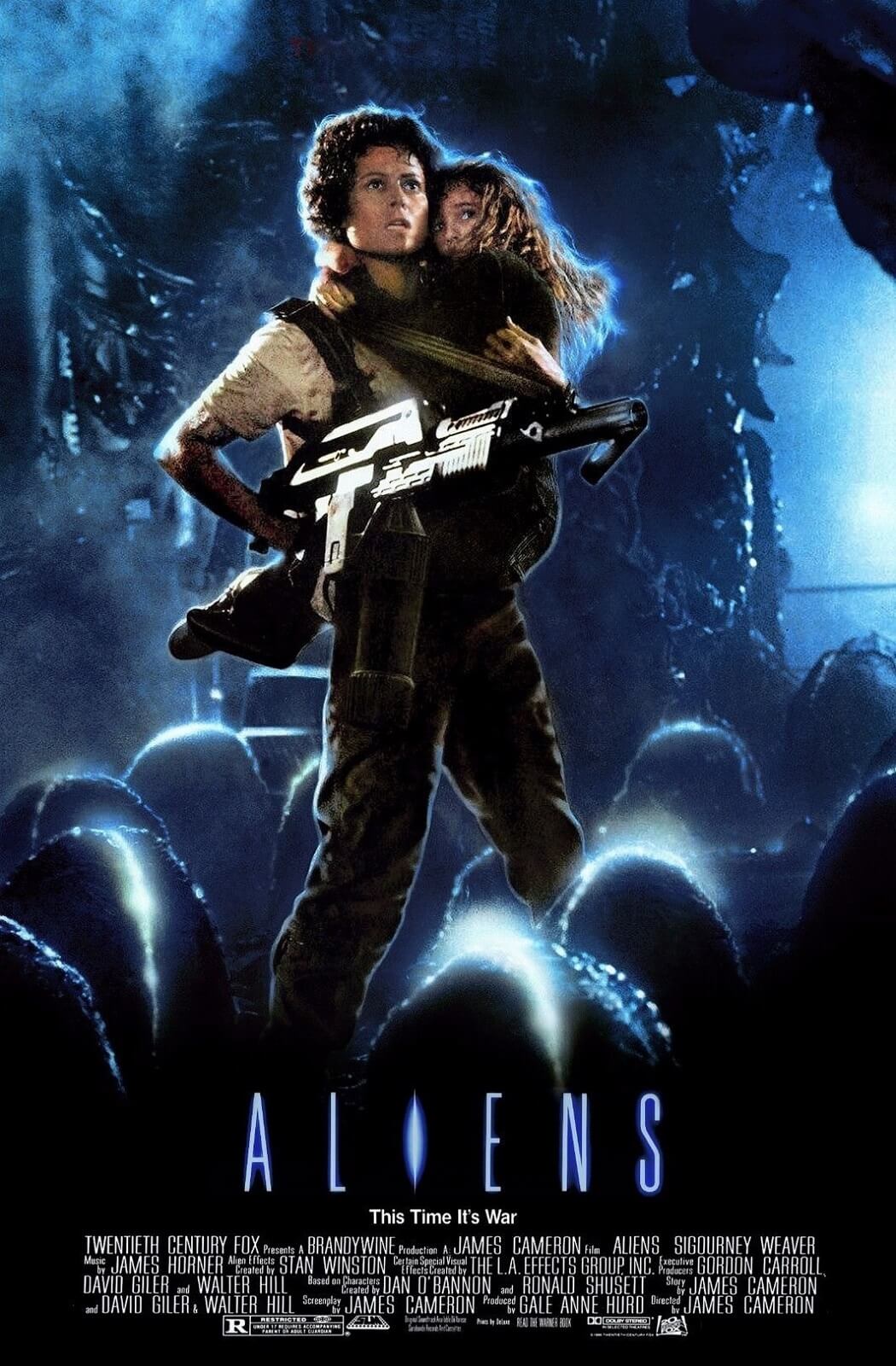

Alien 3 puts yet another inspired visualist behind the camera of the Alien franchise for the third in the series—started in 1979 by Ridley Scott and revisited in 1986 by James Cameron. Following this tradition, in 1992, director David Fincher made a visually distinctive sequel whose outcome was nonetheless considered by most to be a major disappointment. Each entry in the franchise is set apart by the ingrained personal style of its director, who, in turn, marries his own visual signatures with the atmosphere of their science-fiction setting. Scott and Cameron both made superbly innovative films, whereas Fincher, an acclaimed music video director but first-time filmmaker, came into a maligned studio production and was forced to shoot with a limited budget and incomplete script. Thus, his vision is less cemented in the finished film. Still, his presence lingers in the surface polish (or intended lack thereof). Having survived a long and strenuous development and production process, Alien 3 made it to cinemas only after much studio tampering, which led to Fincher eventually disowning the end result. What we’re left with is a film to feel conflicted about but ultimately admire from a minimum safe distance.

Upon its initial release, the film was met with infrequent praise but more often dismissal. Most critics commended its visuals and condemned the story. Roger Ebert did this most succinctly, calling the film “one of the best-looking bad movies I have ever seen.” Reactions to this day insist on comparing Fincher’s film to the franchise’s earlier entries, somewhat unfairly so. Naysayers (Cameron among them) lament how the film destroys what Aliens established in what was supposedly the last chapter in a trilogy, as all beloved characters die and the mood never reaches above somber and funerary. Audiences loved the warm ending and gung-ho American militarism of Cameron’s blockbuster, and by contrast, Alien 3 is filled with a gloomy, largely British cast of characters faced with their inevitable doom. But Fincher’s highly publicized bowing to studio demands during the production doesn’t mean he didn’t leave his signature. His precisely shot, brown-toned treatment contains many of the atmospheric and technical flourishes found later in his career, and he lends the film a weightier push toward spiritual substance than Alien or Aliens. Unfortunately, in the end, the final screen story does little more than provide a pretense through which audiences witness ghastly deaths and the chomping of human fodder into so much gore.

Prior to Fincher’s arrival, Alien 3’s development gave birth to a long list of unrealized concepts and oddball ideas, some of which ended up in its sequel, Alien: Resurrection, but none of which made much sense following Aliens. Brandywine’s David Giler and Walter Hill originally suggested to 20th Century Fox a two-part sequel to Aliens in which Michael Biehn’s character Hicks would take center stage fighting against a corporate conspiracy to genetically engineer xenomorph warriors. The initial script by Neuromancer author William Gibson was to be helmed by Ridley Scott, although the director’s schedule would not allow it, at which point Renny Harlin (Die Hard 2) stepped in. Harlin later left the production after a succession of unsatisfying rewrites. Pitch Black writer-director David Twohy then wrote his own script about Ripley landing on a prison planet wrought by an alien cloning conspiracy, but his idea was scrapped too. The next writer, Vincent Ward, introduced a radical fan-favorite concept where Ripley landed on a wooden satellite amid a group of monks; the presence of a deadly alien represented a kind of religious test for the monks, while Ripley soul-searched for meaning in her connection to the demonic alien species. Ultimately, producers Giler and Hill rewrote the final screenplay themselves, meshing ideas from earlier scripts into an inelegant new amalgamation. The film was green-lit before Giler and Hill finished their new draft; however, Fincher was forced to begin production without a completed script.

Prior to Fincher’s arrival, Alien 3’s development gave birth to a long list of unrealized concepts and oddball ideas, some of which ended up in its sequel, Alien: Resurrection, but none of which made much sense following Aliens. Brandywine’s David Giler and Walter Hill originally suggested to 20th Century Fox a two-part sequel to Aliens in which Michael Biehn’s character Hicks would take center stage fighting against a corporate conspiracy to genetically engineer xenomorph warriors. The initial script by Neuromancer author William Gibson was to be helmed by Ridley Scott, although the director’s schedule would not allow it, at which point Renny Harlin (Die Hard 2) stepped in. Harlin later left the production after a succession of unsatisfying rewrites. Pitch Black writer-director David Twohy then wrote his own script about Ripley landing on a prison planet wrought by an alien cloning conspiracy, but his idea was scrapped too. The next writer, Vincent Ward, introduced a radical fan-favorite concept where Ripley landed on a wooden satellite amid a group of monks; the presence of a deadly alien represented a kind of religious test for the monks, while Ripley soul-searched for meaning in her connection to the demonic alien species. Ultimately, producers Giler and Hill rewrote the final screenplay themselves, meshing ideas from earlier scripts into an inelegant new amalgamation. The film was green-lit before Giler and Hill finished their new draft; however, Fincher was forced to begin production without a completed script.

The film opens with the survivors of Aliens—Ripley, her surrogate daughter Newt, bisected android Bishop, and Ripley’s would-be suitor Hicks—ejected from the military spaceship Sulaco in an escape vehicle only to crash-land on a derelict planet, called Fury 161. Home to an all-but-abandoned maximum security prison now occupied by a few remaining staff and two-dozen inmates, the prison exists on the “ass-end of space,” forgotten and unwanted. Ripley finds herself in similar standings, alone once more as, during the crash-landing, everyone she’s come to love dies. Worse, an acid-blood burn inside their escape pod suggests an alien rode along and perhaps implanted someone onboard. Utterly defeated by her ill fate and the loss of her stand-in family, this Ripley is distant and burdened, and no longer the gun-toting heroine from Aliens. In fact, Fury 161 has no guns whatsoever to tote against the forthcoming alien threat. As she investigates the probability of an alien on the planet, Ripley befriends a doctor-turned-inmate-turned-doctor (Charles Dance) and rivals the prison’s two authority figures (Brian Glover and Ralph Brown). Meanwhile, her presence sets the all-male inmate population (including Pete Postlethwaite, Holt McCallany, Danny Webb, and Paul McGann) on edge. Believing in some apocalyptic version of Christianity, the inmates preach the word of God and struggle with temptation. Their unity brings them together when an alien emerges in their prison, bursting from a dog and determined to kill them all.

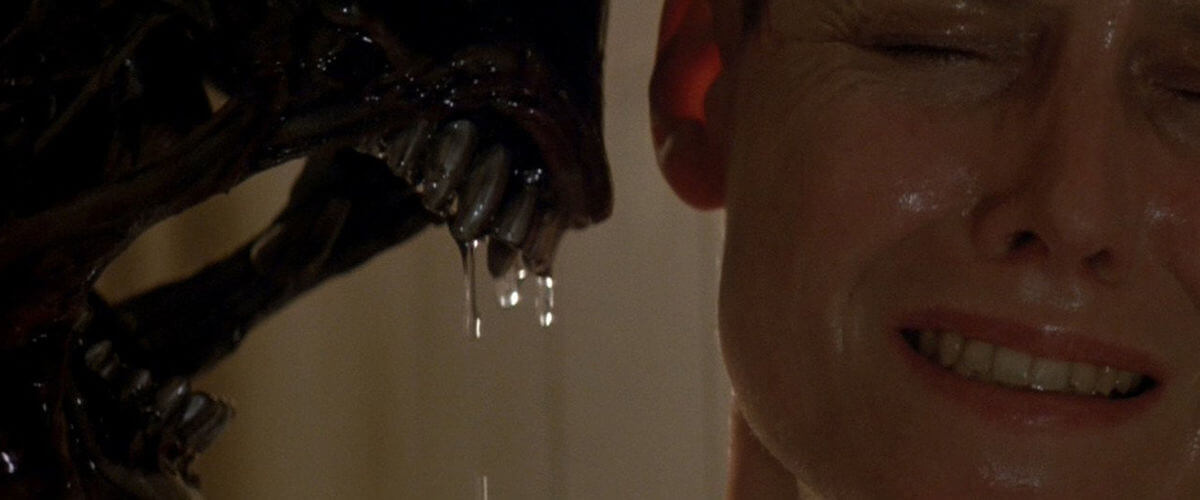

The basic motivations of the creature (designed as a quadruped by original alien artist H.R. Giger and realized by effects artists Tom Woodruff, Jr. and Alec Gills) remain peculiar. Rather than collecting and cocooning its victims as the creature does in the earlier films, this one kills unsparingly, seemingly without purpose, like a masked murderer in a slasher movie. In previous Alien films, when a victim is taken, the victim’s fate is worse than death; they become a host for an alien. But there’s no immediate threat of the species spreading here, save for the alien embryo Ripley discovers gestating inside her. Worse, it’s a Queen, capable of laying eggs and creating countless more. Except, the threat of this on Fury 161 is nil, as the Dog Alien kills every inmate it sight without reservation. Only Ripley is immune to the Dog Alien’s hostility. Moreover, she’s tired of being afraid of the creature, and she wants the alien to kill her and the Queen inside her. But the Dog Alien seems to know there’s a Queen inside Ripley and resists killing her. Even so, the alien has left no potential hosts for its Queen. (NOTE: This poor conflict could have been assisted by a dramatic turn if, say, the Dog Alien had begun to build a nest for its inevitable Queen and stored the prisoners as future hosts. Why? the characters would ask throughout the film, until the big reveal when we learn of the embryo Ripley carries inside her.)

The basic motivations of the creature (designed as a quadruped by original alien artist H.R. Giger and realized by effects artists Tom Woodruff, Jr. and Alec Gills) remain peculiar. Rather than collecting and cocooning its victims as the creature does in the earlier films, this one kills unsparingly, seemingly without purpose, like a masked murderer in a slasher movie. In previous Alien films, when a victim is taken, the victim’s fate is worse than death; they become a host for an alien. But there’s no immediate threat of the species spreading here, save for the alien embryo Ripley discovers gestating inside her. Worse, it’s a Queen, capable of laying eggs and creating countless more. Except, the threat of this on Fury 161 is nil, as the Dog Alien kills every inmate it sight without reservation. Only Ripley is immune to the Dog Alien’s hostility. Moreover, she’s tired of being afraid of the creature, and she wants the alien to kill her and the Queen inside her. But the Dog Alien seems to know there’s a Queen inside Ripley and resists killing her. Even so, the alien has left no potential hosts for its Queen. (NOTE: This poor conflict could have been assisted by a dramatic turn if, say, the Dog Alien had begun to build a nest for its inevitable Queen and stored the prisoners as future hosts. Why? the characters would ask throughout the film, until the big reveal when we learn of the embryo Ripley carries inside her.)

Instead, the producers’ intent to make a full-fledged horror movie proceeds, as the prisoners become anonymous kill points to increase the alien’s body count, each slaughtered in a grislier fashion than the last. Meanwhile, Ripley probes prisoner leader Dillon (Charles S. Dutton) to kill her before the Queen bursts from her chest. He refuses and insists Ripley help lure the alien into the installation’s lead works, where they plan to drown the creature in hot lead. Although Alien 3 contains religious plot elements and characters, the film should not be mistaken as existential or soul-searching, despite the conclusion: The Christ-like Ripley leaps into a vast (and shoddily animated) lead fire to prevent evil corporation Weyland-Yutani from getting an alien specimen, sacrificing herself for the sake of humanity. Vague references to redemption and honor arise throughout the film, but they hardly resonate in any meaningful way. Several subplots involving individual prisoners—most notably when Golic (McGann) betrays his fellow inmates because he identifies with the beast—were cut from the final film, eliminating both important character developments and thematic material. Instead, the film jumps headlong into a surprisingly grim conclusion. The alien has finally bested Ripley, but she has prevented the company from attaining a prospective bio-weapon. The sense of hopelessness is staggering, but ultimately the film ends with Ripley as a sacrificial hero—certainly not the “Rambolina” of Aliens.

How rare and brave even that a major franchise should decide to kill off its central, now-iconic character without the promise of another sequel on the way. Sigourney Weaver, initially opposed to another film in the series after the studio demanded that an abridged cut of Aliens go to theaters (sans scenes involving Ripley’s backstory and the loss of her daughter), gives an intense performance in Alien 3 with subtle gradations. Behind her daringly shaved head, required because the prison is riddled with lice, Weaver’s role goes from quiet mourning to pissed-off heroine to somber martyr. She even finds time for a romantic interlude with the resident doctor. But her character also suffers from a cornball ego; she flaunts her knowledge of the alien’s nesting habits to the prisoners, though in retrospect, her previous xenomorph encounters were brief and introductory at best. Now she talks about the alien like a seasoned pro: “It’s like a lion; it stays close to the zebras.” And later, Weaver is subject to eye-rolling dialogue when Ripley goes looking for the alien on her own: “Don’t be afraid… I’m part of the family.” Lines like this are written for movie trailers, not for actual movies, and yet here they are.

Nevertheless, and perhaps most importantly, Ellen Ripley feels like the character we’ve followed from the earlier films, just now faced with insurmountable odds and fatalistic circumstances. Even rarer than Ripley’s demise is the humorless and pensive tone Alien 3 adopts, whereas Aliens contained glints of comic relief in Bill Paxton’s Hudson, and Alien featured Brett and Parker to lighten the mood, albeit briefly. This grave atmosphere, admirable if offset by the gratuitous bloodshed onscreen, comes in perfect balance with Alex Thomson’s lensing, Fincher’s color-drained style, Norman Reynolds’ industrialized production design, and the gothic score by Elliot Goldenthal. The series dies down here like a campfire with an orange smolder, and so Fincher’s frames look burnt and worn, even while being polished and impeccably framed. He also incorporates ceiling-bound “alien-cam” shots, as the Dog Alien sprints about on vertical walls and overhead during the climactic corridor chase sequence. Fincher’s alien POV shots are effective, but the reverse angle view showing the alien is realized with unfortunate 1990s-quality special FX. Those effects were nominated for an Oscar after the film’s release, yet they have not dated well. The alien itself, for example, is never less than unintelligible in animated form. Its quadruped stance looks laughable (better, I suspect, than Fincher’s original idea of putting an actual dog in an alien costume), whereas the guy-in-a-suit shots of the alien show a biped creature. The resulting effect is confusion from the audience, who never has a clear idea of how this alien moves from scene to scene, but not in the intentional way permeated by Scott on Alien.

Nevertheless, and perhaps most importantly, Ellen Ripley feels like the character we’ve followed from the earlier films, just now faced with insurmountable odds and fatalistic circumstances. Even rarer than Ripley’s demise is the humorless and pensive tone Alien 3 adopts, whereas Aliens contained glints of comic relief in Bill Paxton’s Hudson, and Alien featured Brett and Parker to lighten the mood, albeit briefly. This grave atmosphere, admirable if offset by the gratuitous bloodshed onscreen, comes in perfect balance with Alex Thomson’s lensing, Fincher’s color-drained style, Norman Reynolds’ industrialized production design, and the gothic score by Elliot Goldenthal. The series dies down here like a campfire with an orange smolder, and so Fincher’s frames look burnt and worn, even while being polished and impeccably framed. He also incorporates ceiling-bound “alien-cam” shots, as the Dog Alien sprints about on vertical walls and overhead during the climactic corridor chase sequence. Fincher’s alien POV shots are effective, but the reverse angle view showing the alien is realized with unfortunate 1990s-quality special FX. Those effects were nominated for an Oscar after the film’s release, yet they have not dated well. The alien itself, for example, is never less than unintelligible in animated form. Its quadruped stance looks laughable (better, I suspect, than Fincher’s original idea of putting an actual dog in an alien costume), whereas the guy-in-a-suit shots of the alien show a biped creature. The resulting effect is confusion from the audience, who never has a clear idea of how this alien moves from scene to scene, but not in the intentional way permeated by Scott on Alien.

Other inconsistencies and annoyances occur: Consider the amount of swearing, which is copious enough to earn the Rob Zombie Award for the number of “fucks” used in a single film. Of course, it’s important to remember the characters are primarily hardened murderers and rapists, and their fanatical Christian sect may have vowed them to celibacy, but it didn’t bar them from foul language. This critic can handle any amount of four-letter words, as long as it serves a purpose; here, like the violence, the language is excess for excess’ sake. Then there’s the final scene: nonsensically, the last shot consists of the camera panning over to the EEV on the rubbage heap, where we hear Ripley’s signoff recorded on the Nostromo shuttle at the end of Alien, as if to close out the trilogy by coming full circle. But how did Ripley’s Nostromo recording make it to the Sulaco, and why the heck was it just playing by itself? Who knows.

Whether these inconsistencies are the consequence of an unfocused production or studio tampering, or both, is best known by those involved in the film-making process. Since its release, the sordid production history of Alien 3 has become something of a Hollywood horror story. Fincher, backed by unsure studio heads who wanted a finished product faster and cheaper than he—or anyone else for that matter—could realistically deliver, was put through veritable hell during production. Constant studio supervision, an unfinished script, and reshoots delayed production, while Fincher’s usual drive toward perfectionism was denied by a studio that wanted a gore-fest instead of the intended spiritual, substance-filled motion picture Fincher intended. Finally, when Fincher’s shoot and re-shoots were completed, the studio took the film and edited it to their own demands, resulting in a confusing marketing campaign (trailers claimed Alien 3 would take place on Earth, a promise that confused audiences and critics upon the film’s release) and underwhelming box-office results.

All suspicions about where to place the blame are best answered by Fox’s 2003 “Assembly Cut,” released in their Alien Quadrilogy boxed set on home video. This version contains 30 minutes of deleted and alternate scenes added back into the film and restores some of Fincher’s original vision for the picture, though Fincher himself refused to participate in putting the refurbished cut back together. What we see is a slower-paced film, but one that effectively patches most of the plot and dramatic holes missing from the theatrical version, even in its rough and incomplete assembly format. The prisoners become well-rounded characters. The spiritual themes have time to germinate. It’s simply a better film, and even approaches the level of artistry of its predecessors. One cannot help but lament that some of the lost audio and grainy footage in the “Assembly Cut” couldn’t be restored to better quality, as this film is how I prefer to remember Alien 3.

All suspicions about where to place the blame are best answered by Fox’s 2003 “Assembly Cut,” released in their Alien Quadrilogy boxed set on home video. This version contains 30 minutes of deleted and alternate scenes added back into the film and restores some of Fincher’s original vision for the picture, though Fincher himself refused to participate in putting the refurbished cut back together. What we see is a slower-paced film, but one that effectively patches most of the plot and dramatic holes missing from the theatrical version, even in its rough and incomplete assembly format. The prisoners become well-rounded characters. The spiritual themes have time to germinate. It’s simply a better film, and even approaches the level of artistry of its predecessors. One cannot help but lament that some of the lost audio and grainy footage in the “Assembly Cut” couldn’t be restored to better quality, as this film is how I prefer to remember Alien 3.

Watching this film will forever incite discussion about what it could have been, while little interest revolves around what the film actually tries to be. Whether pondering Vincent Ward’s wooden planet concept or clinging to the faint hope that someday Fincher will put aside his long-harbored grudge to finish a true director-approved cut, those who know the production history will always feel a sense of incompleteness when viewing the film. To be sure, it’s not a satisfying experience, but rather a boldly bitter and disappointing end whose slasher methods and unsympathetic characters feel contrived in the abridged studio cut. What exists onscreen is admirable in technical terms and even in its downer concept, but it lacks artistic freedoms enjoyed by Ridley Scott and James Cameron. A lot of talented people were brought together here for a film the studio simply didn’t want to make. Fortunately, Fincher’s career would immediately recover with Seven, The Game, and Fight Club in the years following, each made with a precision that makes fans of Alien 3 ache over what could’ve been, if only Fox had allowed Fincher his freedom. Yet, somewhere in his footage exists a great finale to an Alien trilogy. Certainly, moments of greatness do occur, while now the film manages to be more fascinating as an oddity than an emotionally involving viewing experience (as Alien and Aliens still are). Production troubles and unintended outcomes aside, this is not a bad film, just one that requires the viewer to look beyond their own expectations to appreciate both what ended up onscreen and what could have ended up onscreen.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review