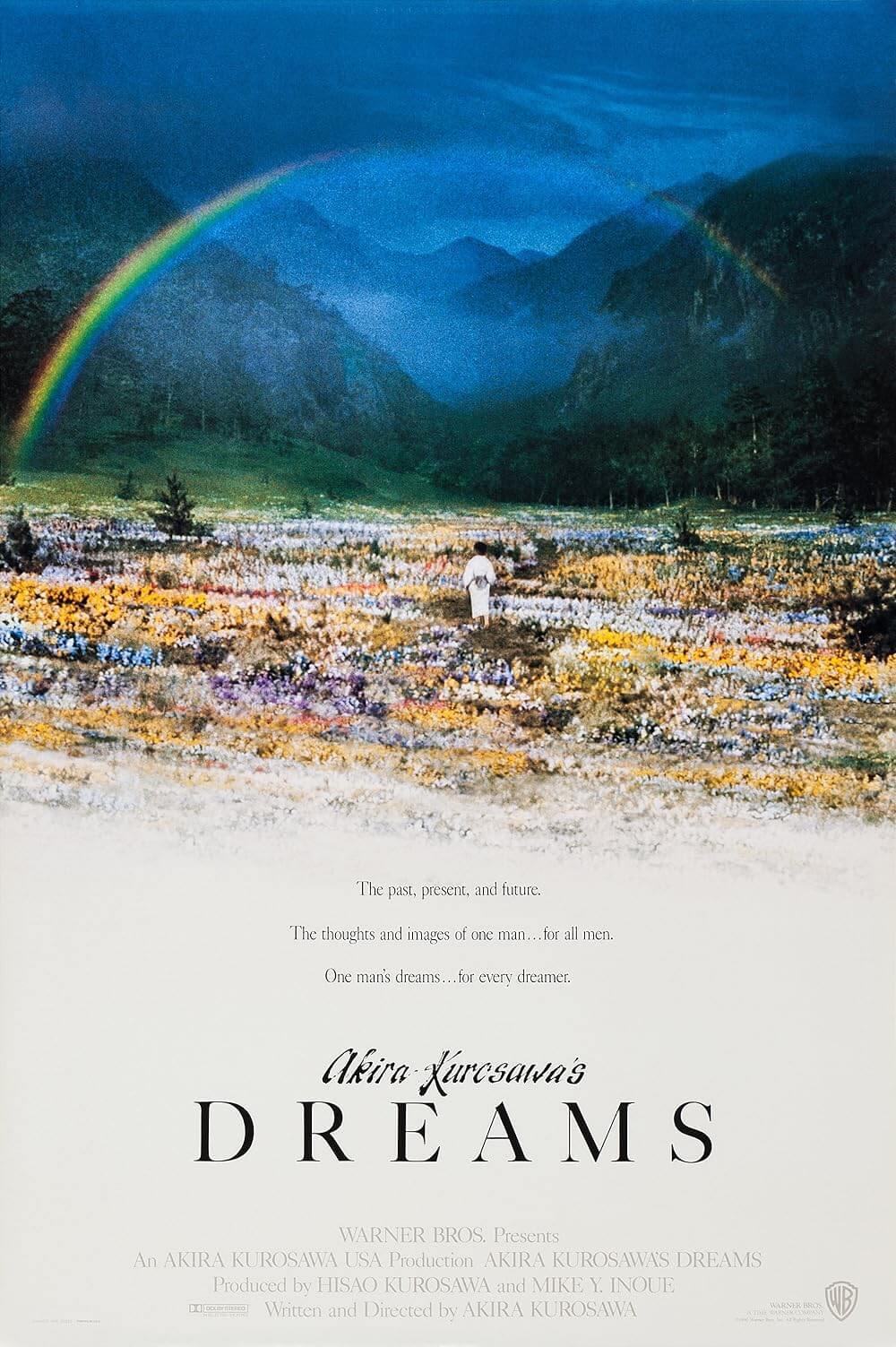

Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams

By Brian Eggert |

Akira Kurosawa’s films explore identity. Any audience, regardless of demographics, can relate because identity is inherent in humanity. His universal themes and ability to evoke a powerful reaction amid international audiences are part of what established his reputation the world over. And yet, in his 1990 film Dreams, the Japanese director engages in a singularly introspective examination to realize his dreams on film; in doing so, he explores the decidedly unique and personal subject of dreams that, by their nature, come from within the psyche of the individual dreamer. With the film, he sets aside any desire to appeal to a specific kind of audience or demographic and instead looks inward, using the art of filmmaking as a mode of personal expression, the way a painter uses oils and canvas to create a masterpiece that never leaves his studio. Perhaps as a result of its personal source and lack of relevance to a wider audience, Dreams remains one of Kurosawa’s least accessible films; nevertheless, it is also among his most intimate pictures, having come from the chamber of his unconscious mind into an expression of pure art.

Kurosawa was in his twilight years when he started work on Dreams. His most popular films (his sixteen collaborations with Japan’s top star Toshiro Mifune, such as Seven Samurai and Yojimbo) had come and gone, as had his heyday. In 1970, his film Dodes’ka-den, his first color picture, debuted as a failure among critics and disappointment at the box-office. Afterward, his longtime studio, Toho, considered him a risk, and the prospect of getting to shoot another film anytime soon seemed unlikely. Kurosawa fell into a deep depression and attempted suicide in 1971. After a short recovery, the director went from making a film each year to a new title only every five years. He remained productive with celebrated titles such as Dersu Uzala in 1975, Kagemusha in 1980, and Ran in 1985, the latter of which was considered by many as the director’s final masterpiece. But these late career films became increasingly inward and reflective; Kurosawa was clearly musing on his age and mortality more than ever before. Nearing the end of his life, it was a time for self-reflection for Kurosawa, who was nearly eighty years old when he began writing Dreams.

According to his personal journal, Kurosawa’s Dreams sought to explore a passage by Fyodor Dostoevsky in which the author claims, “Dreams revealed men’s deepest thoughts, liberated in sleep.” Kurosawa understood the importance of reaching deep inside himself to achieve self-expression; although, pure expression often proved elusive under Toho. Nevertheless, for the first time in his career, he refused to work alongside a co-writing collaborator to tailor his script for an appropriate, studio-friendly treatment. When he finished writing the script after a mere two months, he struggled to find financing and, in time, secured production costs because his longtime admirer Steven Spielberg helped him do so. The film would bring eight of Kurosawa’s most intense and memorable dreams to life in anthology form, adopting an episodic structure with no overarching connective tissue beyond the film’s title. Each of the filmed dreams is preceded by an intertitle announcing, “I had a dream…” or “I had another dream…” And the individual dreams each have their own titles, such as “Sunshine in the Rain” or “Mount Fuji in Red.”

According to his personal journal, Kurosawa’s Dreams sought to explore a passage by Fyodor Dostoevsky in which the author claims, “Dreams revealed men’s deepest thoughts, liberated in sleep.” Kurosawa understood the importance of reaching deep inside himself to achieve self-expression; although, pure expression often proved elusive under Toho. Nevertheless, for the first time in his career, he refused to work alongside a co-writing collaborator to tailor his script for an appropriate, studio-friendly treatment. When he finished writing the script after a mere two months, he struggled to find financing and, in time, secured production costs because his longtime admirer Steven Spielberg helped him do so. The film would bring eight of Kurosawa’s most intense and memorable dreams to life in anthology form, adopting an episodic structure with no overarching connective tissue beyond the film’s title. Each of the filmed dreams is preceded by an intertitle announcing, “I had a dream…” or “I had another dream…” And the individual dreams each have their own titles, such as “Sunshine in the Rain” or “Mount Fuji in Red.”

Upon its release, critics met Dreams with a combination of distanced admiration and suspicion. Many called the film a “vanity project” or work of “self-indulgence,” dismissing the result as far too personal to have resonance with a larger audience. Because the film came from Kurosawa’s own reveries, which derived from his unique identity and unconscious mind, critics found it “hard to care” about the individual stories. Even so, Time Out in London described the series of stories as “misguided and inadequate clichés,” which brings about the question: What is a cliché? A cliché is something so ingrained that it becomes formulary. The word “cliché” is a pejorative and its usage leads to a judgment of taste or value. However, the word also implies something so familiar that it has been overused. Indeed, Kurosawa taps into universal fears, anxieties, and preoccupations in Dreams, and his aesthetic approach to bringing these commonalities to life is anything but cliché.

Presented in vivid, painterly colors captured by cinematographers Takao Saito and Mashaharu Ueda, Dreams finds Kurosawa at his most visually artistic, using the filmic art in the same way many fine artists had in the past—as an act of exploring self-consciousness. Kurosawa studied painting and fine arts in his college years and painted as a pastime throughout the remainder of his life. This is evident in the film’s most visually inspired segment, called “Crows,” in which actor Akira Terao plays Kurosawa’s onscreen counterpart, although the character remains unnamed. Terao stands in an art museum, looking at paintings by Vincent van Gogh. All at once, he finds himself walking into a pastoral world that seems to be accented by Van Gogh’s brush. He explores and soon finds Van Gogh himself, played by Martin Scorsese, painting a landscape. Van Gogh ruminates on his inspiration for art, and the speech seems to reflect Kurosawa’s own view: “A scene that looks like a painting doesn’t make a painting. If you look closely, all of Nature has its beauty… I lose myself in it,” says Van Gogh. “But it’s so difficult to hold it inside.” Terao asks Van Gogh what he does to release this feeling. Van Gogh responds that he works. At this, Van Gogh begins to paint, which transforms this sequence into a cinematic work of painted impressionist landscapes. Terao loses himself in two-dimensional set pieces of Van Gogh’s art. Kurosawa, too, seems to lose himself in Dreams by realizing his innermost thoughts, fears, and unconscious preoccupations.

Presented in vivid, painterly colors captured by cinematographers Takao Saito and Mashaharu Ueda, Dreams finds Kurosawa at his most visually artistic, using the filmic art in the same way many fine artists had in the past—as an act of exploring self-consciousness. Kurosawa studied painting and fine arts in his college years and painted as a pastime throughout the remainder of his life. This is evident in the film’s most visually inspired segment, called “Crows,” in which actor Akira Terao plays Kurosawa’s onscreen counterpart, although the character remains unnamed. Terao stands in an art museum, looking at paintings by Vincent van Gogh. All at once, he finds himself walking into a pastoral world that seems to be accented by Van Gogh’s brush. He explores and soon finds Van Gogh himself, played by Martin Scorsese, painting a landscape. Van Gogh ruminates on his inspiration for art, and the speech seems to reflect Kurosawa’s own view: “A scene that looks like a painting doesn’t make a painting. If you look closely, all of Nature has its beauty… I lose myself in it,” says Van Gogh. “But it’s so difficult to hold it inside.” Terao asks Van Gogh what he does to release this feeling. Van Gogh responds that he works. At this, Van Gogh begins to paint, which transforms this sequence into a cinematic work of painted impressionist landscapes. Terao loses himself in two-dimensional set pieces of Van Gogh’s art. Kurosawa, too, seems to lose himself in Dreams by realizing his innermost thoughts, fears, and unconscious preoccupations.

To be sure, Kurosawa’s Dreams involves inherently personal and individual subject matter, as though it was intended to serve as a release for Kurosawa himself and no one else. Given this, he realizes his most purely artistic motion picture, even while he incites an inner dialogue within his audience about their own dreams and consciousness. The effect on his audience is perhaps an unintentional consequence of Kurosawa’s exploration of his dreams, as he chose just eight dreams from his entire lifetime of dreaming, but he unconsciously selects dreams with common archetypes to empower his film with universal observations relatable to the collective unconscious. Kurosawa’s choices may have been fueled by his years as a successful filmmaker and intrinsically knowing what audiences want to see; and yet, the director insisted his choices were random and unconnected. Regardless of its intention as either self-expression or a more widespread appeal, Dreams shows Kurosawa demonstrating the power of art as a method through which individuals find personal meaning and self-understanding.

Kurosawa saw himself as “unformed,” according to his book Something Like an Autobiography. His art served as a method for the artist to explore himself and his world. As a filmmaker, he was interested in how people form themselves in relation to a particular situation. “He is not at all interested in what forces have made people what they are,” wrote Kurosawa’s biographer Donald Richie, “He is completely interested in what people make out of what the forces have made of them.” In effect, Kurosawa sought the root of individual humanity. Perhaps this is why he remains one of the most communally celebrated filmmakers on an international scale. When he died on September 6, 1998, more than thirty-five thousand attended his funeral, among them friends, colleagues, and avid fans from around the world. His films brought together countless people from around the planet through his universal themes and questions that remain fundamental to any human being.

Kurosawa saw himself as “unformed,” according to his book Something Like an Autobiography. His art served as a method for the artist to explore himself and his world. As a filmmaker, he was interested in how people form themselves in relation to a particular situation. “He is not at all interested in what forces have made people what they are,” wrote Kurosawa’s biographer Donald Richie, “He is completely interested in what people make out of what the forces have made of them.” In effect, Kurosawa sought the root of individual humanity. Perhaps this is why he remains one of the most communally celebrated filmmakers on an international scale. When he died on September 6, 1998, more than thirty-five thousand attended his funeral, among them friends, colleagues, and avid fans from around the world. His films brought together countless people from around the planet through his universal themes and questions that remain fundamental to any human being.

If this assessment of Dreams lacks a detailed discussion of film’s individual stories or its filmmaking, it’s because so many commentators have already appreciated its beauty or investigated the details of its admittedly simple stories. At the same time, those critics have marginalized and even censured the film’s personal intentions. But Dreams functions just as every Kurosawa film does—as the director’s search for knowledge and understanding of how people behave, what they yearn for, and what aspects of their lives are universal. As a whole, his films look for essential and common human traits. Kurosawa’s entire body of work pursues an understanding humanity’s place in the world, which remains one of the few common characteristics of every human being. Dreams finds Kurosawa’s search pointed inward, but it is no less relevant or affecting universally. By appreciating Kurosawa as an investigator of human behavior, Dreams becomes something far more than the self-indulgent vanity project of an elder auteur; it becomes an essential film for humanity.

Sources:

Galbraith IV, Stuart. The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune. New York: Faber and Faber, 2002.

Richie, Donald. The Films of Akira Kurosawa, Third Edition, Expanded and Updated. With additional material by Joan Mellen. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1996.

Richie, Donald; Schrader, Paul. A Hundred Years of Japanese Film: A Concise History, with a Selective Guide to DVDs and Videos. Tokyo; New York: Kodansha International: Distributed in the U.S. by Kodansha America, 2005.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review