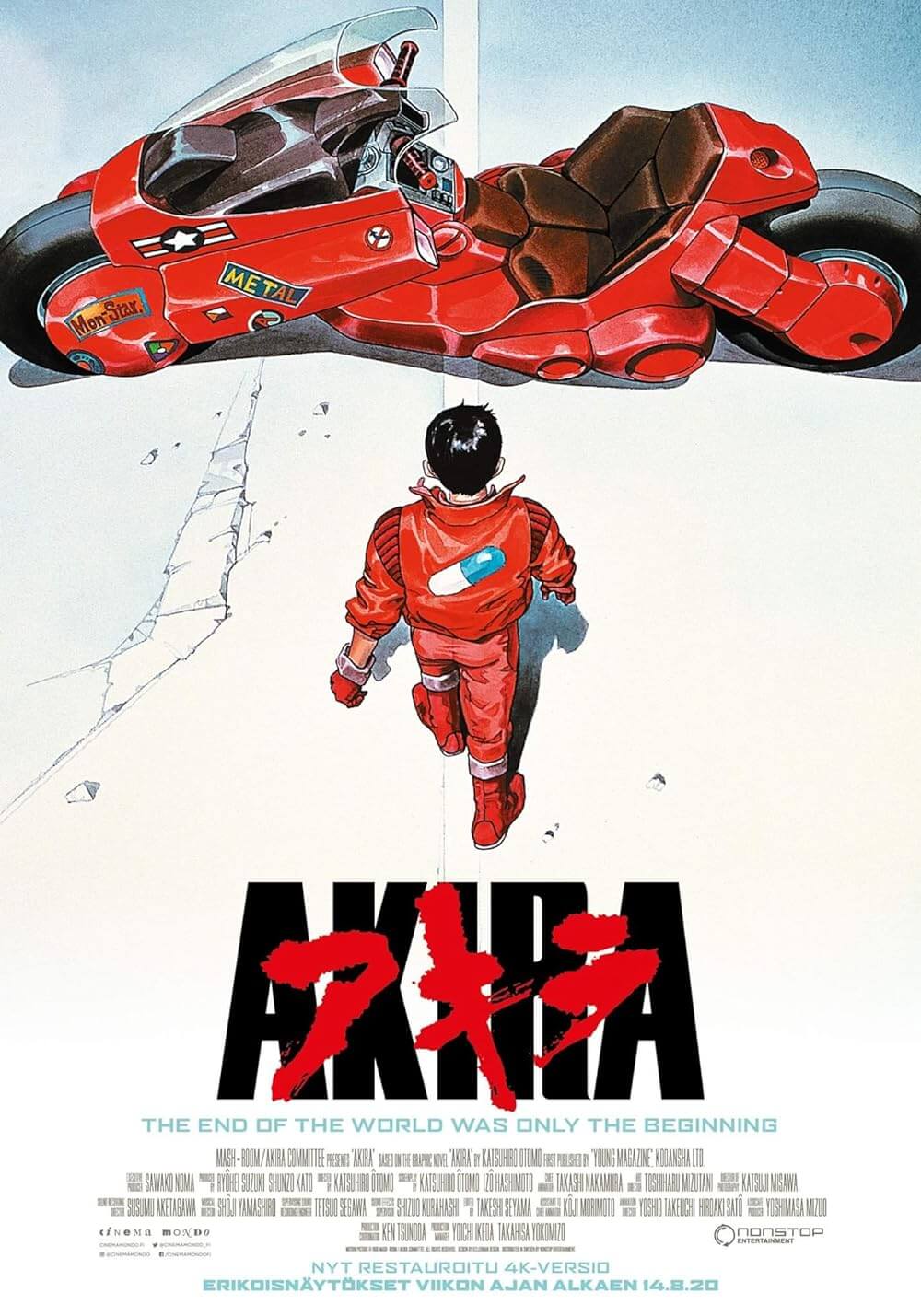

Akira

By Brian Eggert |

Akira begins in 1988 with a shocking image. A massive, seemingly atomic explosion erupts in downtown Tokyo and ignites World War III. After the war is over thirty years later, Neo-Toyko has grown out of the rubble into a metropolis of bright lights and impossibly high skyscrapers. Political demonstrations fill the streets, and militaristic government forces resort to extreme violence to stop them. Youth biker gangs buzz the highways and engage in deathly road battles. And top-secret government experiments have resulted in strange, warped children with incredible powers. This is the frightening, thrilling cyberpunk world created by Katsuhiro Ohtomo, the manga artist and anime director whose vision would inspire countless other Japanese artists and Hollywood film directors in the years to come. His film, released in 1988 and still regarded as one of the most important anime pictures ever released, transcends the medium’s limitations through its incredible production value, substantial influence, unforgettable designs, and a lasting commentary on the state of Japanese cultural identity. Whereas anime has an unfortunate reputation of being more about style than substance, Akira stands as a rare exception.

Otomo first published his manga Akira in 1982 in the pages of Youth Magazine, a weekly source of manga in Japan, published by Kodansha. Grounded in the emerging cyberpunk subgenre, its roots most prevalent in the William Gibson book Neuromancer (1984), Otomo’s planned six-volume series would not be completed until 1990 after more than 2,000 published pages. However, as with many popular manga series, its author was eventually approached to translate his story into an anime completed before the manga was finished. (Another notable example of this trend can be found in Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, the manga first published in 1982, the film released in 1984.) But Otomo’s vision was too great for any single production studio, and Otomo, who demanded creative control, would not accept any less than a complete realization of his vision. And so, The Akira Committee was formed, representing a conglomeration of Japanese companies—including Toho Co., Ltd., Bandai Co., Ltd., publisher Kodansha Ltd., and several others—determined to finance and co-produce Otomo’s manga into an unprecedented $11 million project, comprised of 160,000 cells of meticulously detailed animation, which made back eight-times its budget at the international box-office.

The film opens when a teen biker gang called the Capsules, led by the chummy Kaneda, engages another group called the Clowns. During the road brawl, Kaneda’s temperamental best friend Tetsuo crashes into a small, curiously aged boy with telekinetic powers. All at once, government ships arrive to take Tetsuo and the graying, wrinkled boy away. Kaneda’s gang undergoes interrogation, unaware that the boy was a test subject sprung by rebels from a government installation where scientists attempt to imbue special children, called Espers, with “the power of a god.”

The film opens when a teen biker gang called the Capsules, led by the chummy Kaneda, engages another group called the Clowns. During the road brawl, Kaneda’s temperamental best friend Tetsuo crashes into a small, curiously aged boy with telekinetic powers. All at once, government ships arrive to take Tetsuo and the graying, wrinkled boy away. Kaneda’s gang undergoes interrogation, unaware that the boy was a test subject sprung by rebels from a government installation where scientists attempt to imbue special children, called Espers, with “the power of a god.”

Tetsuo soon undergoes the same experiments under the supervision of Dr. Onishi and his military commander Colonel Shikishima, who attempt to replicate the indefinable power of one Esper named Akira, a boy whose powers were so great that they caused the explosion in Tokyo decades earlier. But Tetsuo’s natural abilities are unleashed by Dr. Onishi and quickly grow unstable and uncontrollable, transforming him into a violent, hallucinating, and power-hungry maniac determined to set Akira, who survives only as dissected organs contained in jars, free from his cryogenic underground prison. Meanwhile, Kaneda pines after Kei, a member of a rebel faction determined to destabilize the corrupt and irresponsible government. Kei and Kaneda soon realize that they’re both after the same thing, although not ideologically. When he discovers what’s become of Tetsuo, Kaneda joins the rebels if only to recover his best friend and stop him from destroying all of Neo-Tokyo.

In Japanese anime, realism and style have a strange interplay that remains its defining visual motif. With its roots in manga, the anime artist commands both elements and takes complete control. In the case of Akira, Otomo’s realism presents itself in the form of painterly images depicting the incredible iridescent cityscape of Neo-Tokyo, the images only slightly less fantastic than the futuristic vision of Ridley Scott for his Tokyo-inspired Los Angeles in Blade Runner (1982). On the other hand, Otomo employs a more comic-book stylization elsewhere, particularly in the less weighty and more actionized or comic relief scenes involving Kaneda. Anime often has these juxtapositions of style and tone, but few blend as well as Otomo’s approach in Akira.

His massive scope celebrates the glorious Neo-Tokyo, but his entertaining and thrillingly composed action sequences don’t betray, except in pitch, the other more grandiose visuals. With anime, sometimes the need for multiple artists working on a single film results in an inconsistency of style. Still, Otomo’s production spared no expense to bring uniformity to the screen. The result is awe-inspiring at times and completely immersive. At the same time, Otomo’s reach, given his unquestionably cinematic approach, becomes evident everywhere, from countless other Japanese anime films such as Ghost in the Shell (1995) to live-action works like The Matrix (1999) and The Fifth Element (1997). But the film is much more than attractive visuals, sci-fi concepts, and rousing motorbike action.

It’s impossible to watch Akira’s opening scenes and not immediately think of the United States’ bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II. In the years to come, postwar Japan would grow overpopulated and Westernized. The country’s rampant economic growth would lead to what is considered the epitome of futuristic cities: modern-day Tokyo—a metropolitan orgy of neon lights and busy streets. Developed and exaggerated in science-fiction and manga, the Tokyo of the future becomes a metaphorical epicenter for everything wrong with postwar Japan, how national identity is warped and perhaps lost in the desire to rebuild without restraint. In the hands of cyberpunk authors, the reconstruction has led to a disgusting but fascinating and sometimes beautiful degree of excess, which, based on Akira’s finale, demands complete obliteration before there’s any hope of true recovery. Humanity and certain freedoms are lost in this process, but the technology and sheer visionary requirements needed to give form to the future undeniably enthralls. However, as much as Akira slyly critiques postwar Japan and the era’s reshaping of the city and culture, its effects on human beings are far more invasive.

It’s impossible to watch Akira’s opening scenes and not immediately think of the United States’ bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II. In the years to come, postwar Japan would grow overpopulated and Westernized. The country’s rampant economic growth would lead to what is considered the epitome of futuristic cities: modern-day Tokyo—a metropolitan orgy of neon lights and busy streets. Developed and exaggerated in science-fiction and manga, the Tokyo of the future becomes a metaphorical epicenter for everything wrong with postwar Japan, how national identity is warped and perhaps lost in the desire to rebuild without restraint. In the hands of cyberpunk authors, the reconstruction has led to a disgusting but fascinating and sometimes beautiful degree of excess, which, based on Akira’s finale, demands complete obliteration before there’s any hope of true recovery. Humanity and certain freedoms are lost in this process, but the technology and sheer visionary requirements needed to give form to the future undeniably enthralls. However, as much as Akira slyly critiques postwar Japan and the era’s reshaping of the city and culture, its effects on human beings are far more invasive.

Beyond the technology, the individual undergoes a similar reconstruction in Otomo’s hands, specifically in Tetsuo. Kidnapped and subject to unknowable experimentation, Tetsuo hallucinates in dream imagery that would frighten Dali. In one gory sequence, his entrails spill out onto the ground in a pile, and he desperately tries to pull them back inside; another sequence shows a nightmarish dream where stuffed animal projections transform into towering monsters. Tetsuo’s head begins to expand. As he develops instantaneous telekinetic powers, he acts out in jaw-dropping displays of violence and destruction. He loses all sense of his history and devotion to his friends. Soon his body grows a strangely fleshy arm to replace a lost appendage, a formless and fluid thing that at once seems to reflect post-atomic radiation mutations, as well as the all-too-quick changes that Japanese youths were forced to endure. By the finale, Tetsuo’s arm grows into Akira’s enormous body, freed into a gob of flesh and machine that leaves one queasy. Tetsuo himself might be a metaphor for postwar Japan, growing out of control. In less graphic terms, Akira represents its youth as counter-culture rebels fighting either against the system or engaged in criminal gangs, either way, against authority in every form. This is the tragedy of Otomo’s future as it relates to his characters, presenting a cynical allegory for how postwar Japan has been unrecoverably influenced, body and soul.

After twenty-five years, Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira still inspires awe. As a seminal work of anime, cyberpunk or otherwise, it still has yet to be matched in its epic stature. Hollywood has tried for more than a decade to produce a live-action adaptation, resulting only in false starts. But no amount of expensive computer-animated special FX, star power (names involved have included Leonardo DiCaprio, Keanu Reeves, and Garrett Hedlund), or blockbuster production value could ever match the singular vision Otomo achieved in 1988. His limitless spectacle of a nuked world reborn into a frightening dystopian city—teeming with the subgenre’s usual range of cyberpunks, telekinetics, and authoritarian bad guys—may overshadow the emotional depth of his characters and their often overly expositional dialogue. But Otomo’s audience is so rapt by the proceedings that these criticisms hardly seem important. Akira remains so densely steeped in spectacle, out-there sci-fi ideas, and an overload of visual information that its social and cultural commentaries may go overlooked. Despite this unbalance, such an extraordinary achievement demands to be seen and seen again for re-evaluation into its deeper relevance—and to be appreciated as a landmark not just of anime but of international cinema.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review