Air

By Brian Eggert |

Ben Affleck’s Air charts Nike’s campaign to sign Michael Jordan to a shoe line in 1984. At the time, Jordan hadn’t yet played on an NBA court. But the eventual contract for Air Jordans launched the Chicago Bulls player into the sports celebrity stratosphere and redefined what athletes could expect from partnering with brands. Told with palpable admiration for the future shoe and basketball player, the film is an unabashed love letter crafted by superfans. Affleck and screenwriter Alex Convery recognize that Jordan, who went on to become a billionaire and a sports icon, started as an underdog. He was recognized by another of his kind, Nike, then a flailing shoe company bested by Adidas and Converse. By detailing their mutual success, Affleck tells a quintessentially American story of a self-made man who becomes a legend thanks to his skill and business acumen. Even so, Jordan is peripheral in Air, given its focus on the shoe company—specifically Nike executive Sonny Vaccaro, played by Matt Damon, who was smart enough to recognize what many in the NBA draft did not: Jordan’s inevitable greatness.

A story about shoe executives negotiating an elaborate business deal might sound like a dull subject matter for a movie. It’s even less savory after Affleck, playing Nike’s New-Agey CEO Phil Knight, makes a passing, mildly conflicted reference to his company’s use of East Asian sweatshops while finalizing a deal that will earn them billions. Nevertheless, Air is the latest in 2023’s string of brand biopics that detail the creation of a popular product. Just two weeks before the debut of Affleck’s film, AppleTV+ bowed Tetris, about the licensing deal that brought the Soviet-made video game to the world—a movie so wrapped up in contract mumbo jumbo that it forgot to build memorable characters. To be sure, few films have done this sort of story well; those that have inject the narrative with a human element and make the brand mere dressing. For instance, what would The Social Network (2010) be without the so-called friendship between Mark Zuckerberg and Eduardo Saverin as a microcosm of how people would use their platform in the future? But Affleck’s film enlivens what could have been a series of dry marketing pitch conferences into a high-stakes affair performed by a terrific cast.

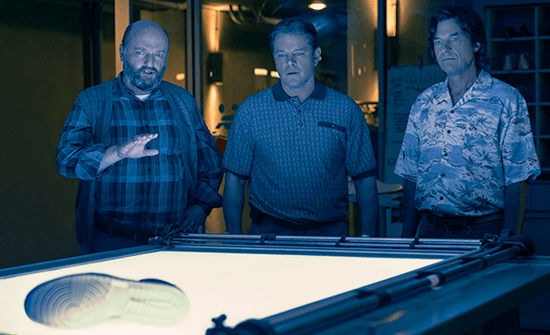

Air centers on Vaccaro, who Knight pressures to find new players to build Nike’s basketball shoe line. Their competition dominates the industry, leaving Nike only 17% of the market share. Four years have passed since the company went public, and Knight has started to worry that, unless he makes some significant strides, he won’t be able to keep his board of directors from cutting the basketball division and focusing on running shoes. Then Vaccaro sets his sights on Jordan. In various walk-and-talks, men’s room convos, and meeting room debates, Vaccaro makes his case that he will need to use the entire endorsement budget—$250,000 intended for three players—on Jordan alone. Eventually, Vaccaro, a gambler accustomed to making choices based on a gut feeling, earns the backing of executives Howard White (Chris Tucker) and marketing head Rob Strasser (Jason Bateman). But Jordan (Damian Young, seen only from behind) won’t even take a meeting with Nike, according to his acidic agent (Chris Messina, hilariously brash). No matter, since the person Vaccaro needs to convince is Jordan’s mother, Deloris (Viola Davis), the family matriarch and the player’s top advisor.

Although the film concerns little more than debates about basketball and business—two subjects that could not interest me less—the charming cast and persistent humor keep Air appropriately light and engaging. Regardless of the potentially dry topic, Affleck has made a crowd-pleaser dependent on Damon’s charm and Bateman’s knack for dry sarcasm, and both are considerable. The scenes involving eccentric basement-dwelling shoe designer Peter Moore (Matthew Maher) contain a few inspired asides about what makes Air Jordans unique to their player (“He doesn’t wear the shoe. He is the shoe; the shoe is him.”), and somehow avoid feeling like a commercial for Nike. And a thoughtful scene with coach-turned-consultant George Raveling (Marlon Wayans) reveals a moving bit of history on the fringes of the Jordan deal, even though it pumps the brakes on the film’s momentum. But Affleck manages the lighter business proceedings and tense pitch sequences with a nimble touch, involving the audience in every moment, even as he barely investigates his characters’ personal lives. The sole exception is Strasser, who worries that he might lose his job if the deal fails, which makes the rather spartan Vaccaro realize that Nike is only a company because of its people.

Although the film concerns little more than debates about basketball and business—two subjects that could not interest me less—the charming cast and persistent humor keep Air appropriately light and engaging. Regardless of the potentially dry topic, Affleck has made a crowd-pleaser dependent on Damon’s charm and Bateman’s knack for dry sarcasm, and both are considerable. The scenes involving eccentric basement-dwelling shoe designer Peter Moore (Matthew Maher) contain a few inspired asides about what makes Air Jordans unique to their player (“He doesn’t wear the shoe. He is the shoe; the shoe is him.”), and somehow avoid feeling like a commercial for Nike. And a thoughtful scene with coach-turned-consultant George Raveling (Marlon Wayans) reveals a moving bit of history on the fringes of the Jordan deal, even though it pumps the brakes on the film’s momentum. But Affleck manages the lighter business proceedings and tense pitch sequences with a nimble touch, involving the audience in every moment, even as he barely investigates his characters’ personal lives. The sole exception is Strasser, who worries that he might lose his job if the deal fails, which makes the rather spartan Vaccaro realize that Nike is only a company because of its people.

Air marks Affleck’s first time behind the camera since 2016’s Live by Night, an underrated gangster drama about bootleggers in Florida. That film was preceded by his Best Picture winner, Argo (2012); his Boston bank robber thriller, The Town (2010), improved in the extended cut with an alternate ending; and his debut, the 2007 kidnapping mystery Gone Baby Gone. In the years between his last film and Air, Affleck has been caught in the DCEU superhero shitstorm, donning Batman’s cape and developing a solo movie that fell apart. Given his evident skill as a director, it’s a shame he was detoured and took so long to make another movie. Air is a welcome addition to his filmography. The star-studded cast speaks in snappy dialogue reminiscent of, but less stagey than, Aaron Sorkin’s work in The Social Network. They inhabit the dreary 1980s office aesthetic captured by production designer François Audouy and wear schlubby clothes designed by costumer Charlese Antoinette Jones. It’s a convincing portrait of an eccentric past, evidenced by Knight’s jogging suits, bare feet, and mono-lens sunglasses.

To be sure, from moment one, Air takes an unabashed nostalgia trip. Affleck leans into his 1984 setting, beginning with Dire Straits’ “Money For Nothing” set against editor William Goldenberg’s pop culture and politics montage. There’s not so much a score as pervasive needle drops selected by music supervisor Andrea von Foerster—an almost nonstop procession of hits from Run-D.M.C.’s “My Adidas” to songs by The Violent Femmes, Night Ranger, and George Clinton. The soundtrack could have supplied the music to that “Back to the ’80s” party your company had ten years ago. Visually, Affleck and cinematographer Robert Richardson capture the muted complexion of the period, but the bravado camerawork offsets the drab corporate colors. Richardson’s fluid maneuvering around the office environment, following the intense executive debates, might even go unnoticed because the actors do wonders with the material. Although many of the actors hardly deviate from their usual onscreen personas, the screenplay gives Damon and Davis three powerhouse encounters that add a human dimension to the capitalistic drives on display.

Beneath the surface-level appeal of Nike, Air Jordans, Jordan himself, and remember-when details, Air contains a parable for America—signaled by Vaccaro’s conversation with Strasser about Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” Strasser notes that it’s not a patriotic tune, despite the title; instead, it’s about the individual feeling abandoned by the establishment. In the end, Nike gets their deal with Jordan, of course, but only after agreeing to Deloris’ last-minute demand for a revolutionary revenue-sharing agreement. It ensures that Jordan won’t be forgotten or used up by corporate greed like the character in Springsteen’s song. Jordan’s success story changed how athletes work with companies. As end titles inform us, Vaccaro helped fight on players’ behalf to ensure colleges couldn’t use their likenesses without the athlete getting paid. Affleck and Damon have followed this example with their new production company, Artists Equity, which encourages “entrepreneurial partnerships” with a profit-sharing model similar to what Jordan negotiated with Nike.

Given this, Air feels less like the crass celebration of capitalism that was Tetris and more like an example of conducting a less exploitative and more inclusive business. Even though the film takes only a half-hearted stance against the unacceptable working conditions of Nike factories, the script isn’t an unconditional celebration of American business. Air acknowledges that even as the American system will build Jordan up, it also loves to tear down its heroes. And so, regardless of the tabloid drama in Jordan’s life after reaching household-name status, his legacy endures. This is not only because Jordan became the NBA’s champion but because his family had enough foresight not to allow a corporation to take advantage of him. Such remarks remain secondary to the film’s playful ’80s sheen, constant humor, and excellent cast, but they’re present nonetheless, elevating Air to more than just a feature-length commercial.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review