Agora

By Brian Eggert |

If science proved that the Earth isn’t the center of the universe, why do many religions still suggest that humanity is the central concern of a higher power? Should that ideal not have faded along with the notion that the Sun revolves around our small planet? Of course it should have. But once they’re in power, religious authorities have a way of overlooking that they were proven wrong, if only to cling to their power. And the more they cling to a fading ideal, the more twisted and abstract their ideologies become. History shows a disturbing circle of one weaker ideology crumbling for another, more powerful one, which in the end has little to do with who was right. Rather, victory resides with the ideology that has the most force behind it.

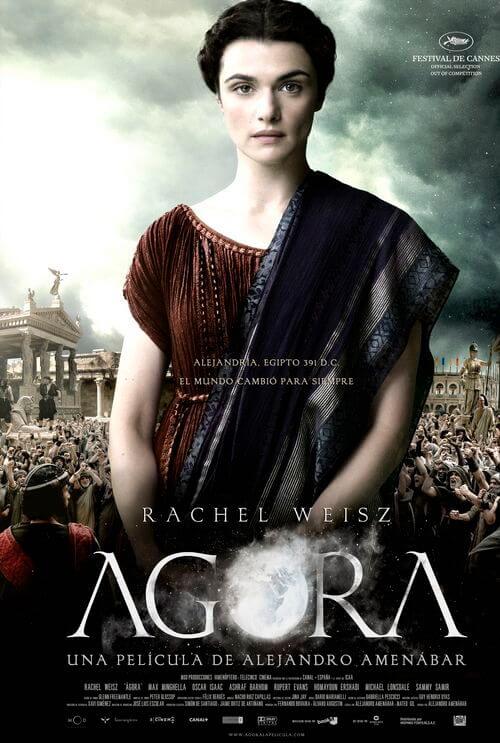

Alejandro Amenábar’s Agora implies a history of intolerance, backward thinking, bloodshed, and sheer insanity in the name of religion. Beginning in 391 AD, the story concerns Hypatia (Rachel Weisz), the top librarian, mathematician, and philosopher in Roman Egypt’s city of Alexandria. She was also a devout secular humanist of the most impressive degree. When the film opens, Hypatia’s vast library of scrolls represents the last remaining intellectual center of the Pagan empire of Rome. All around the city, the burgeoning presence of Christianity threatens to destroy the remaining Pagans and even the library, which houses a wealth of human history, regardless of its religion. In her lectures, Hypatia attempts to find common ground between classes of both Pagan and Christian students. Yet, she is destined to fail.

Historical epics usually offer swords and scandal, very often lusty sex, grandiose set pieces, and bloody battles. They’re escapist works that transport audiences to another place in history so that we might see how humanity hasn’t changed all that much since the dawn of time. Though, Amenábar (director of The Sea Inside and The Others) and his co-writer Mateo Gil don’t put forward your typical historical piece here. Their story is filled with ideas more than the spoils of pure entertainment—something on par with Ridley Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven, except without all those wowing battles. Ironically illustrating a circular cycle of violence between Pagans and Christians and Jews, the filmmakers reduce the arguments to their basics (my imaginary friend is better than your imaginary friend) in favor of Hypatia’s transcendent questions.

Romance can’t help but find its way into the story. Admiring Hypatia’s idealism is her former student-turned-Prefect of Alexandria, Orestes (Oscar Isaac), and her former servant-turned-Christian goon, Davus (Max Minghella). After the Christians turn the few remaining Pagans into converts, Orestes stands over the city and the Christians turn their angry eyes to the Jews. Lead by Cyril (Sami Samir), the Christians demand that Orestes bow to Christ’s influence, which according to scripture, claims that women should remain silent and not hold any position of power. Why else would Christ have only an all-male clan of disciples? As Hypatia is Orestes’ most trusted advisor, he’s forced into betraying her.

As these religious and political games are played, Hypatia retains her place of study. Throughout the film, she continues to ask questions that are beyond any talk of scriptures or religions. For most of her life she has looked up at the stars confounded, as none of the primary explanations (Ptolemy, Hipparchus, etc.) for how the universe works have made sense. Over the years as the story unfolds, Hypatia grows closer and closer to discovering that the Earth revolves around the Sun, and not in a circular orbit, but an ellipse, which wouldn’t be suggested again until Johannes Kepler in the 17th century. However sketchy these ideas may be, historically, they provide a “bigger picture” of the madness going on in the city of Alexandria.

From a production standpoint, the film is gorgeous. Production designer Guy Dyas (Inception) places us in a version of Alexandria that had long ago seen its prime. Paintings have faded; carvings are chipping; structures are crumbling. Colors are windswept and very clearly surrounded by unforgiving desert. This looks like a world that is fading away, but its most impressive trait is also just surface value. Yet, Agora’s ideas cannot replace its deficient central protagonist. The talented Weisz disappears into the role, as she often does, but there’s little for her to do aside from postulate about the workings of the universe. By the end, the audience comes no closer to understanding why Hypatia is driven by her quest for truth. Her character is merely present to ask these questions, so that the viewer might ask analogous questions today, with her ultimate death serving as a tragic reminder that beliefs can serve as a dangerous enemy to truth.

The title suggests that the film itself is a forum for discussion. Though not as blatantly preachy as something like Lions for Lambs, the film does concern itself with the ideologies of its subject more than its dramatic significance, which can be a fatal flaw, but it doesn’t totally devastate this picture. Amenábar implies, but never overemphasizes modern-day parallels to the religious and political climate depicted here. When the Pagan-controlled Alexandria is stormed by Christian mobs, Amenábar evokes an undeniable equivalent to the cultural destruction and thievery that took place in Baghdad not long ago. Atrocities committed in the name of religion against opposing ideas, historical documentation, and the preservation of culture have no end in human history. Admirable only from a distance, Amenábar’s film is a good-looking example of that, even if he does forget to involve the viewer’s emotions as much as their intellect.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review