Aftersun

By Brian Eggert |

This review has been expanded from one originally posted as part of a dispatch from the 2022 Twin Cities Film Fest.

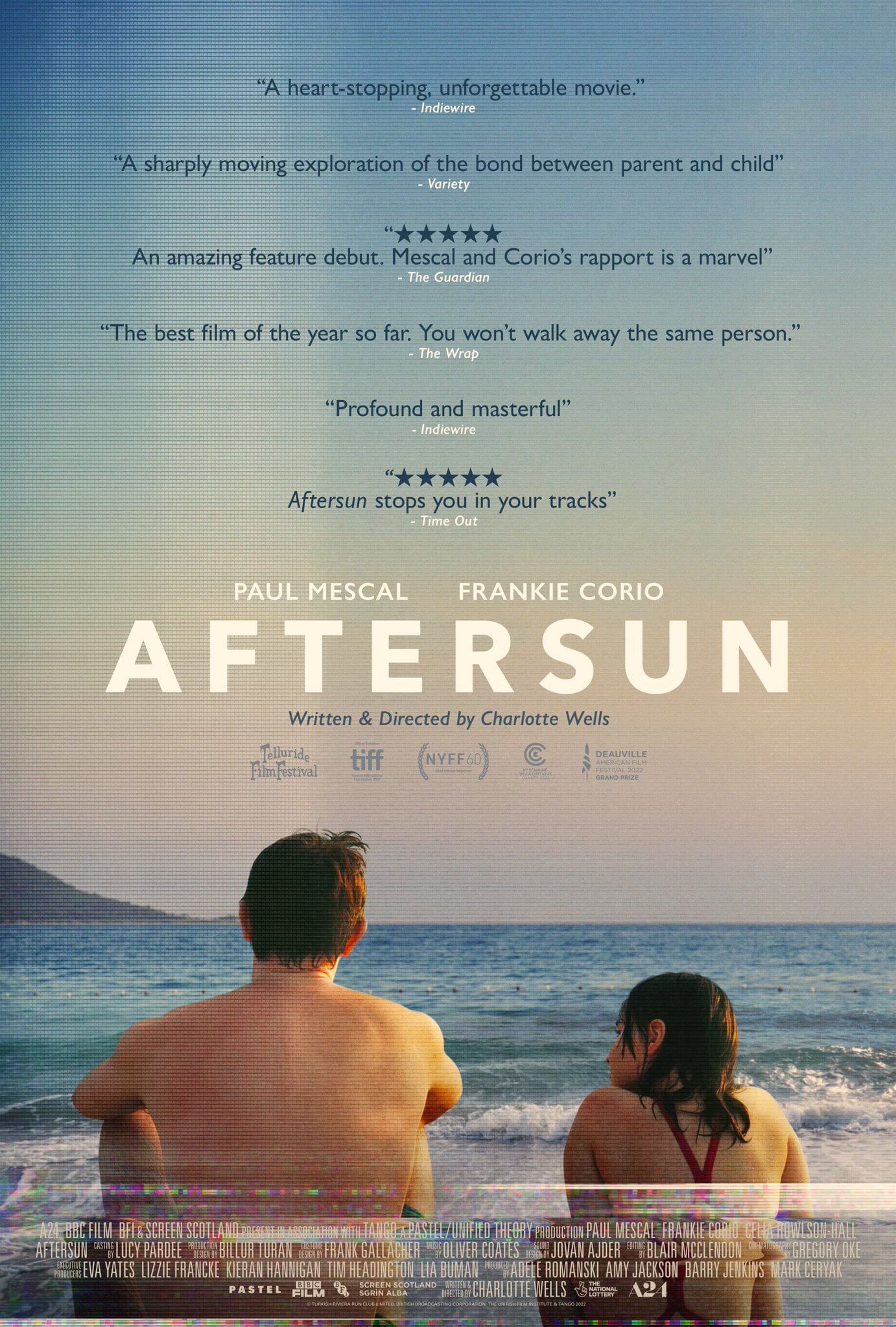

Scottish filmmaker Charlotte Wells explores memory, time, and perception in her debut feature, a formally and structurally sophisticated film about a woman’s recollections of her father. Aftersun premiered at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival, where it earned the French Touch Prize, awarded by the official Critics’ Week Jury to spotlight “audacity and creativity” in a filmmaker’s early work. Wells certainly earns that distinction here, with a film situated in the distortions of recorded video and incomplete memories. In a technique that doesn’t immediately reveal itself, Wells incorporates video captured on a mini DV camcorder with a series of memory-images whose origins remain complex, often rendered in hypnotic, overlapping transitions and leaps in time. The story, centered on Calum (Paul Mescal) and his 11-year-old daughter Sophie (Frankie Corio) on vacation, weighs how memory and video can each deceive and illuminate. Aftersun‘s blend of image sources makes for a fluid, searching composition and a rather profound emotional study of reassembled experiences. It’s all the more powerful for the affecting father-daughter relationship at the center.

Wells sets the film in the 1990s at a westernized resort on the Turkish Riviera—though, the viewer only gleans this information from Sophie’s No Fear hat, a performance of “Macarena,” and other subtle signifiers. The writer-director resists expositional information about Calum and Sophie, but their situation remains readable as the film unfolds. Calum, separated from Sophie’s mother and floundering, has a long history of career plans and money-making angles, but on the cusp of 31, he’s no closer to finding himself, and his stack of books on Tai Chi isn’t helping. Still, it gives him an excuse to teach Sophie self-defense in an amusing scene. Calum is a wounded man, evidenced by his struggle to sleep at 3 a.m., heavy drinking, and allusions to his estrangement from his parents. Unable to grow up, he remarks in one scene that he “barely made it to 30,” and he can’t imagine himself at 40. But he’s also aware of his failings as a father, such as not having enough money to buy Sophie what she wants, even if his lack of money leads to a hilarious dine-and-dash scene. Their vacation consists of lazy sequences by the pool, a few cheap activities around the resort, and the occasional trip to a local marketplace and mud bath. But the way that Wells conveys these events from various perspectives makes the seemingly banal become fascinating.

Meanwhile, Sophie is on the verge of adolescence, so she’s somewhat oblivious to her father’s apparent depression, sensitivity, and need for serious help. Unmistakably, there’s love between them, but they’re also in their respective heads much of the time. She’s not yet to the point where Calum’s presence alone is embarrassing, but she’s also starting to explore boys and show interest in teenagers at the resort. Although she’s much younger than them, she joins a few teens in a game of doubles at the pool table and lingers one night when they’re drinking. And at various points in their vacation, she races a boy on a motorcycle arcade game; he will later become her first kiss. To be sure, she has also begun to think about sex with some uncertainty, such as eavesdropping from a bathroom stall on a private conversation about teen sex or observing two men kissing in a hallway. Calum can see her pulling away from him, more than she already has, and rather than accept this, he responds with childish behavior—most achingly when Sophie urges him to sing karaoke, but he refuses. So she performs a pathetic rendition of REM’s “Losing My Religion” onstage alone in a devastating scene. Rather than join her, he lets her fail, only to later suggest that he could help her get singing lessons. Not that he could afford it, Sophie responds in a barbed comeback.

Mescal is terrific at conveying Calum’s tenderness toward Sophie and his searching energy that remains unsettled but guarded for his daughter’s sake. Corio is a natural, giving an unaffected child performance. Their dynamic feels less like screen drama and more like moments in time captured onscreen—both literally, on the camcorder, and in terms of its emotional veracity. Yet, there’s another presence in the film, shown in a confusing array that ultimately reveals the dramatic scenes to be memory-images and cinematic projections from Sophie’s mind. The older Sophie (Celia Rowlson-Hall), now turning 31 just as her father had on their vacation together, looks back from adulthood and considers what she missed 20 years earlier. But these scenes, which take place now, never quite land in the same way the others do, so they feel like an afterthought. The older Sophie’s presence amounts to a handful of brief shots and flashes in the 101-minute runtime, including short scenes where the adult Sophie dances in a strobe light in a crowd. Later, she sees her father dancing, and, along with the final shot, Wells creates another manner of projection altogether, constructed by Sophie’s imagination.

Mescal is terrific at conveying Calum’s tenderness toward Sophie and his searching energy that remains unsettled but guarded for his daughter’s sake. Corio is a natural, giving an unaffected child performance. Their dynamic feels less like screen drama and more like moments in time captured onscreen—both literally, on the camcorder, and in terms of its emotional veracity. Yet, there’s another presence in the film, shown in a confusing array that ultimately reveals the dramatic scenes to be memory-images and cinematic projections from Sophie’s mind. The older Sophie (Celia Rowlson-Hall), now turning 31 just as her father had on their vacation together, looks back from adulthood and considers what she missed 20 years earlier. But these scenes, which take place now, never quite land in the same way the others do, so they feel like an afterthought. The older Sophie’s presence amounts to a handful of brief shots and flashes in the 101-minute runtime, including short scenes where the adult Sophie dances in a strobe light in a crowd. Later, she sees her father dancing, and, along with the final shot, Wells creates another manner of projection altogether, constructed by Sophie’s imagination.

Wells and editor Blair McClendon arrange the film in a manner that raises questions about every scene and its origin. At least some of what Wells depicts occupies either an objective perspective or the older Sophie’s projection of what she imagined happening. For example, there’s a point when Calum sets out alone one night and walks into the ocean. And in a later scene, after Sophie arranges for vacationers to sing for her father on his birthday, Wells finds him alone, naked, and crying. Such behaviors are neither witnessed by the camcorder nor Sophie directly. Of course, elsewhere, the camcorder records as a source of documented truth, which helps the adult Sophie compile her projections—in the shape of hazy and interwoven memories. Indeed, Aftersun also features a hypnotic comingling of sight and sound, where images from Calum and Sophie’s poolside daze blend from hang gliders to their view of the ocean, creating a dreamlike series of transitions that evoke the illusory passing of time. But Wells also crafts brutally raw moments driven by stark realism, including a scene where Calum spits at himself in the mirror out of self-hatred. Still, we must wonder, did this happen, or has Sophie created this potent scene in her mind? Such questions will continue to haunt and transfix the viewer long after the film is over.

Wells was inspired to make Aftersun after exploring old photographs of her family vacations. But rather than translate those experiences into a straightforward nostalgia-fest or a personal work of autofiction—Wells calls the film “emotionally autobiographical” in the press notes—she used those photos as a catalyst to explore the tricky way memory can either deceive or reveal. As a result, Wells’ film would make for an intriguing case study in Deleuzian film theory, since it raises questions about what images contain and what they omit. Her film, sometimes ponderous in the vein of auteurs such as Argentine director Lucrecia Martel (Zama, 2018) or Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky (Solaris, 1972), makes us question what we are seeing and the emotions that inhabit the spaces between recorded events and memory—and further, how these elements are braided through perception. Although her drama occasionally features pointed moments, such as the song selection of “Under Pressure” by David Bowie and Queen, complete with the lyric “This is our last dance” set against Calum and Sophie’s last dance on vacation, the tenderness of the film never falters. Neither do its lessons about how life sometimes works in a series of patterns that we can only recognize after gaining some distance and perspective. Aftersun is perhaps the most formally intricate and complex film I’ve seen in 2022, and it rewards contemplation beyond its emotionally eviscerating effect.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review