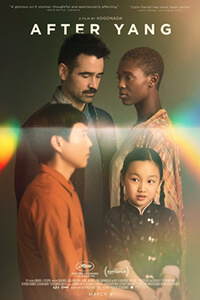

After Yang

By Brian Eggert |

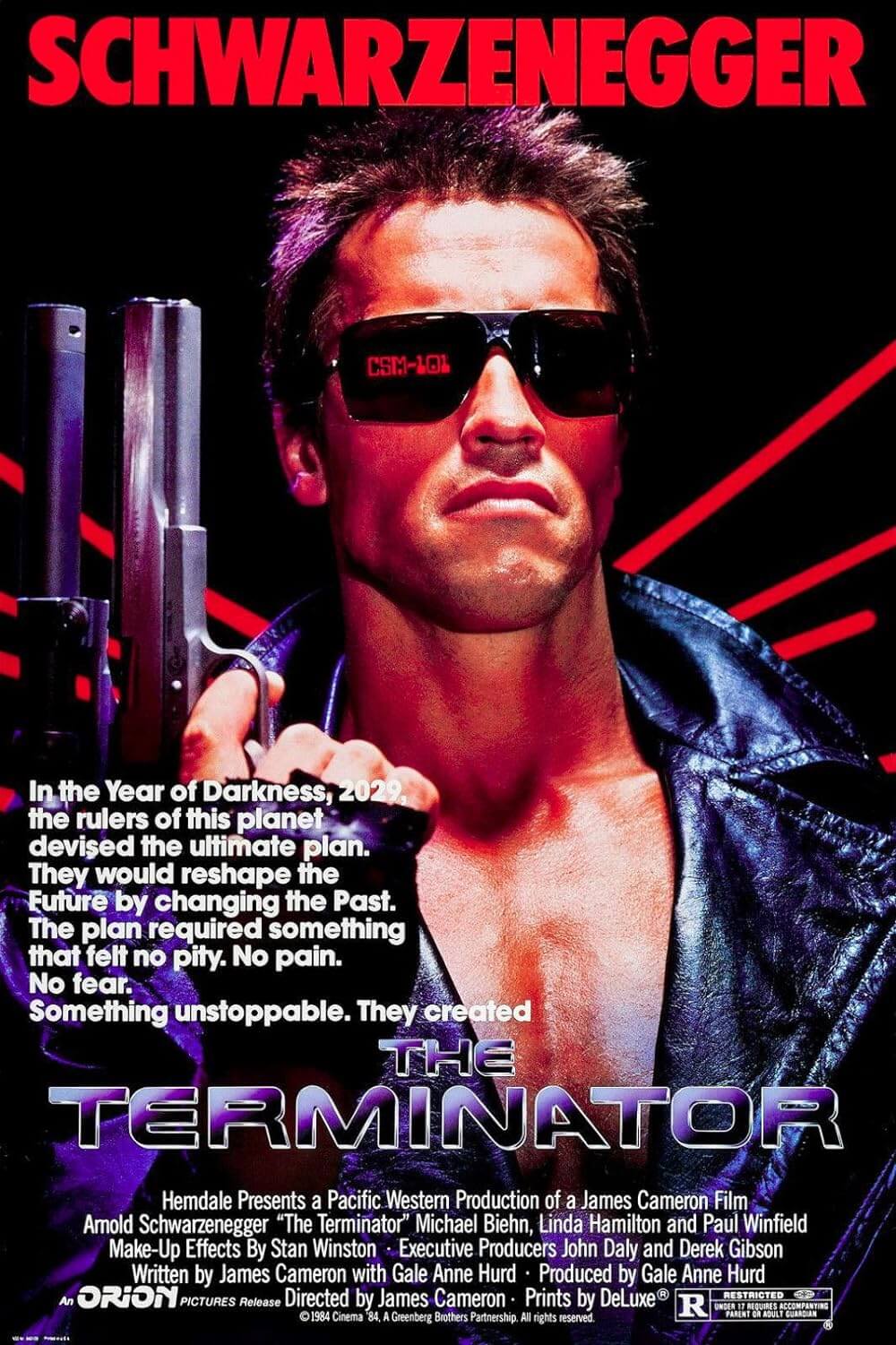

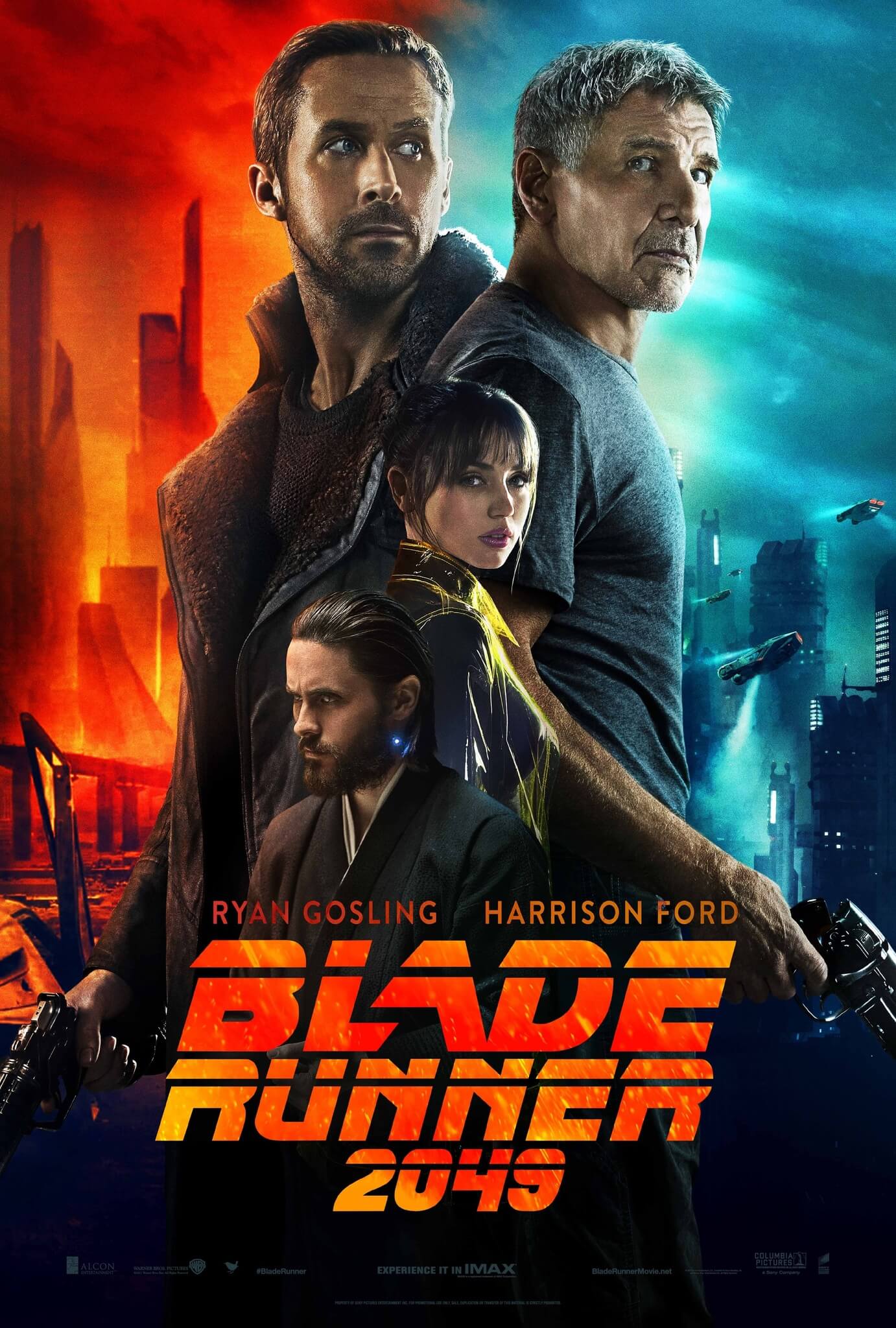

After Yang asks questions about whether an artificial intelligence has a consciousness. Vital in the science-fiction genre, such questions usually uncover the power dynamics between the creator and the robot—between the colonizer and colonized (in Blade Runner, 1982), between men and woman (in Ex Machina, 2015), or the robot’s capacity for desire and dreams (in A.I. Artificial Intelligence, 2001). In the second film by Korean-American filmmaker Kogonada, an exquisite formalist renowned for his video essays that explore the aesthetic components of great filmmakers, the director’s questions about consciousness serve as a platform to search within the otherwise indifferent exterior of a family robot, and therein confront matters of Asian identity. Justin H. Min plays the titular Yang, occupying what Westerners might call the inscrutable Asian man trope. What lies behind such stereotypical reservedness? That’s the question driving aspects of After Yang, but it also serves as a social commentary about how the West understands, or fails to understand, Asian cultures.

The film takes place in a distant future, after a war involving America and China that led to the widespread adoption of Chinese children. “Technosapiens” like Yang have been created to give Chinese children not only a companion but to teach them about their heritage. Yang serves as both brother and caretaker to Mika (Malea Emma Tjandrawidjaja), the adopted Chinese daughter of a struggling American couple, Jake (Colin Farrell) and Kyra (Jodie Turner-Smith). When Yang malfunctions, Mika feels distraught, as though she’s lost her best friend or sibling. By contrast, Jake and Kyra feel inconvenienced. It’s as though their washing machine has broken down, and now their busy schedules will be in disarray because they have to deal with laundromats and repair services in the interim. When Jake sets out to have Yang repaired before the biological exterior decomposes, he encounters a maze of bureaucracy, a paranoid off-the-books technician (Ritchie Coster), and a sympathetic tech-museum curator (Sarita Choudhury) before gaining access to Yang’s memory core, which he reviews behind smart glasses.

After Yang features impressive attention to form and structure, especially in creating a distinct future. Kogonada and production designer Alexandra Schaller craft a world inflected with Asian influences, including an integration of plant life and living spaces. Everywhere you look, there are florae or sculptures, wood carvings, or paintings of vegetation. Plants even live inside the film’s automobiles, which run on a quiet track like the magnetic pods in Minority Report (2002). Every detail from the architecture to the set decoration feels intentionally placed. The sound design, too, has been compellingly presented—and those who watch the film with inadequate sound systems will be robbed of the 360-degree construction of the soundscape, giving the impression that we’re watching After Yang from within a virtual reality simulator. When Jake enters the virtual storage space of Yang’s memories, we see a vast, geometric network of thought bubbles. Each contains a few seconds of Yang’s experience, which Yang selected. When Jake accesses these memory gifs, the viewer feels steeped in that experience—and “steeped” is an intentional metaphor since Jake works as a tea maker, and tea becomes the concept through which he understands Yang’s memories and humanity.

In a discussion about tea, Jake explains to Yang that he became interested after seeing the 2007 documentary All in This Tea (delivering an amusing Werner Herzog impersonation in the process). That film introduces the notion of tea leaves absorbing aspects of their surrounding environment and passing a hint of that world onto the drinker. Similarly, Jake experiences Yang’s world through the accumulated micro-experiences. Kogonada presents them in a series of poignant montages that underscore what Yang found important. We see Malickian through-the-trees shots, moments with Mika, and observations of nature—all captured with Benjamin Loeb’s immersive cinematography in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio. By contrast, scenes outside Yang’s memories appear in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio, which seems narrower and restrictive. The distinction differentiates Jake’s moments using the smart glasses to explore Yang’s core and suggests that memories feel more expansive and immediate than everyday life.

In a discussion about tea, Jake explains to Yang that he became interested after seeing the 2007 documentary All in This Tea (delivering an amusing Werner Herzog impersonation in the process). That film introduces the notion of tea leaves absorbing aspects of their surrounding environment and passing a hint of that world onto the drinker. Similarly, Jake experiences Yang’s world through the accumulated micro-experiences. Kogonada presents them in a series of poignant montages that underscore what Yang found important. We see Malickian through-the-trees shots, moments with Mika, and observations of nature—all captured with Benjamin Loeb’s immersive cinematography in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio. By contrast, scenes outside Yang’s memories appear in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio, which seems narrower and restrictive. The distinction differentiates Jake’s moments using the smart glasses to explore Yang’s core and suggests that memories feel more expansive and immediate than everyday life.

Individually, the images in Yang’s core don’t amount to much, and not much is done with the notion that they’re part of an elaborate spyware conspiracy by Yang’s manufacturers. However, Yang’s memories hint at the identity that collected these moments. Patterns emerge, as does an artful form of expression through his chosen bits of memory. In terms of the plot, they reveal the recurrent presence of Ada (Haley Lu Richardson), a cloned woman who had a secret relationship with Yang in this life and in that of her original. Their relationship raises all sorts of questions about whether or not technosapiens can create emotional connections with other people, which interests Choudhury’s museum curator perhaps more than Jake. For Kogonada’s part as director and editor, he seems most interested in the notion of how memories form the root of experience and identity. Throughout the unfolding drama, he shows significant scenes in the narrative as a repetitious patchwork of jump cuts and alternate takes. The implication is this: If our lives in our minds are nothing more than a patchy and often uncertain assemblage of memories, how is Yang’s life any less genuine?

Adapted from the short story “Saying Goodbye to Yang” by Alexander Weinstein, Kogonada’s script doesn’t offer much emotional resolution beyond its conceptual exploration of memory and identity. As a result, After Yang feels incomplete as a feature film, like two-thirds of an entire narrative. Jake makes a stirring discovery about Yang’s inner life, but Kogonada doesn’t explore the implications of that discovery, nor does he allow the other characters much significant closure afterward. When the film ended with an abrupt cut, I found myself thinking, “That was it?” and wanting more—especially after the film opened with a dazzling title sequence of synchronized dancing. Will Mika overcome her grief from losing Yang? Will the undefined tensions between Jake and Kyra ever be resolved? What exactly did Jake learn from the experiences inside Yang’s memories, apart from how to identify with his technosapien? The ambiguous answers to these questions leave a nagging sense of dissatisfaction after a film that I wanted to keep exploring well beyond the final shot—and not in a way that proves satisfyingly out of grasp. Worse, the grandly melodramatic score by Aska Matsumiya and Ryuichi Sakamoto overaccentuates the low-key drama and hints that we should be feeling more than we do.

The resolution that Yang’s existence “mattered” feels like an underwhelming spot to leave this story since it obviously mattered to Mika in the first place. That it finally mattered to Mika’s detached, even robotic parents who don’t take the time to learn about her heritage for themselves, and therefore place themselves at a distance from that aspect of Mika’s life, feels underemphasized. But, of course, that’s the point. Farrell and Turner-Smith give performances that mirror Min’s, in that everyone, technosapien and human alike, restrains their emotions behind an exterior. Kogonada challenges the viewer to look past the aloof and cool outside and investigate the person inside, hidden in the details. Although this idea resonates when considered from an intellectual perspective, the emotional reality of the film operates at a lesser depth. And so, I find myself enjoying the experience of writing about After Yang more than I did watching it. That might be the sign of a masterpiece or an ambitious letdown.

Still, I find myself drawn to the ideas floating around in After Yang. Consider how this is a world in which humans hold prejudices against technosapiens and clones, much like our world does against various races and cultures—an apparent non-issue in this multicultural and multiracial cast. Given this, After Yang offers a cerebral and restrained study of what it means to be human, specifically Asian, in a world that discriminates. Moreover, when Ada mentions that Yang often wondered if he was really Chinese late in the film, it also reveals itself as a film about what it means to be Asian in the wake of vast globalization and cultural homogenization under American capitalism. All of these ideas have been compiled by Kogonada in a form-follows-function execution that feels like a reflection of Yang’s mind—a random collection of bits and pieces that hint at a whole. Like the best films, After Yang gives us much to consider, even though it feels more ponderous and nebulous than one might prefer.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review