Adam

By Brian Eggert |

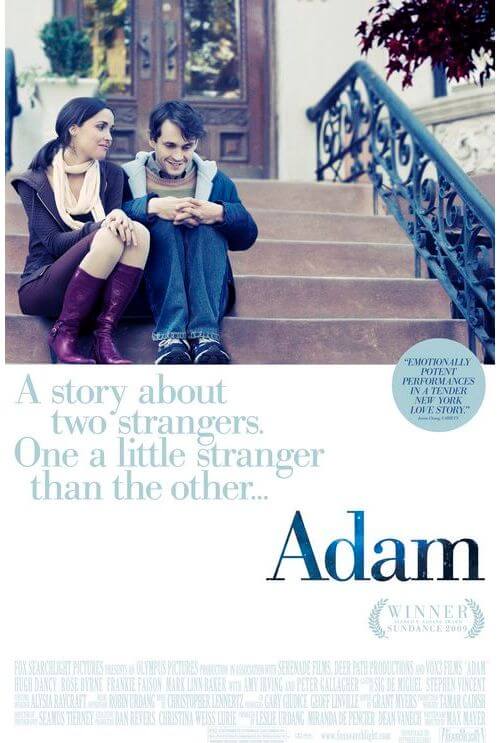

One of the best performances of 2009 is unfortunately contained within a movie that doesn’t live up to the acting. The performance is given by Hugh Dancy and the movie, Adam, is named after his character. It tells the story of a man with Asperger’s syndrome, which is a high-functioning form of autism. Basically, Adam has a hard time deciphering metaphors—he cannot “read between the lines” or interpret body language, nor can he sense what others are feeling through intuition. He’s extremely good with facts, however, particularly those concerning astronomy. The story takes off when he meets a girl, Beth (Rose Byrne), and they engage in an unlikely and touching romance.

Passing by him in their apartment building, Beth finds Adam an attractive and idiosyncratic fellow. They talk in brief, amusing conversations. He takes her to Central Park where he’s found a family of raccoons. It’s shyly romantic. She doesn’t realize he has Asperger’s until he tells her, and then she understands some of his strange behavior—his lacking social filter, for instance. He’s sensitive to her needs but also bluntly honest, asking if she “wants sex” and so forth. On the other hand, he cannot pretend to want to see her friend’s newborn baby, nor can he just know when she needs a hug. However complicated his condition makes their relationship, Adam loves her; it’s evident as he wants to spend time with and place his trust in Beth. He may not be able to reach down into his soul and find the words that Beth needs to hear to be convinced, but his feelings are there.

Beth’s well-to-do parents, Marty and Rebecca Buckwald (Peter Gallagher and Amy Irving respectively), don’t know what to make of Adam at first. Rebecca ultimately thinks he’s just what Beth needs, but Marty, ever the elitist, would prefer she marry an investment banker. Then things get muddled when Marty, a high-powered accounting executive, is indicted on charges of fraud. He’s faced with potential prison time, and somehow this impacts Adam and Beth’s relationship. Her parents come between the couple, who had enough troubles on their own, and that’s where the movie ceases to hold our involvement.

The main reason to see this movie would be the performances by Dancy, a Brit, and Byrne, an Australian, who disappear into their respective American characters. Had you not known that they weren’t born and bred in the States, you’d never know they weren’t; their accents are flawlessly hidden. More than that, though, the leads are able to communicate their roles through their eyes. Watch Dancy’s portrayal and how he never quite looks at anyone directly; even when he learns how to look at someone’s forehead to make it appear as though he’s looking them in the eyes, there’s something on Dancy’s face that tells us he’s employing this trick. And Byrne’s sad, upturned eyebrows, help add depth to a character that in the end we grow frustrated with—her character’s sudden lack of patience and understanding seem to contrast what we learned about her before. After all, she’s a schoolteacher—shouldn’t she be able to read people, Asperger’s or not, and know by their eyes what they’re feeling?

Writer-director Max Mayer meant for Adam’s condition to serve as a metaphor for how communication between people becomes jumbled by misunderstandings and misinterpretations, how that even without Asperger’s syndrome communicating your feelings clearly or reading the feelings of others is almost impossible. With that in mind, the scenes dwelling on Marty’s court case and his relationship with Beth find a logical place within the story. But they do a gross disservice to the movie’s emotional effect by taking away from Adam and Beth’s romance. It would have been enough to simply tell the story of two lovers that grow throughout the movie; alas, that’s not what Mayer has done.

A missed opportunity for something considerably superior, Adam contains impressive performances and challenging material. But the movie loses most of its appeal when it tries to be more than the complex romance it could’ve been. Instead of exploring the character and the central relationship, our connection to Adam and Beth is lost in humdrum courtroom scenes and squabbles with her father. All the movie needed was to be a romance flummoxed by the main character’s Asperger’s and how those two worked through the inherent complications. In trying to be more than that, Mayer loses his audience.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review