Ad Astra

By Brian Eggert |

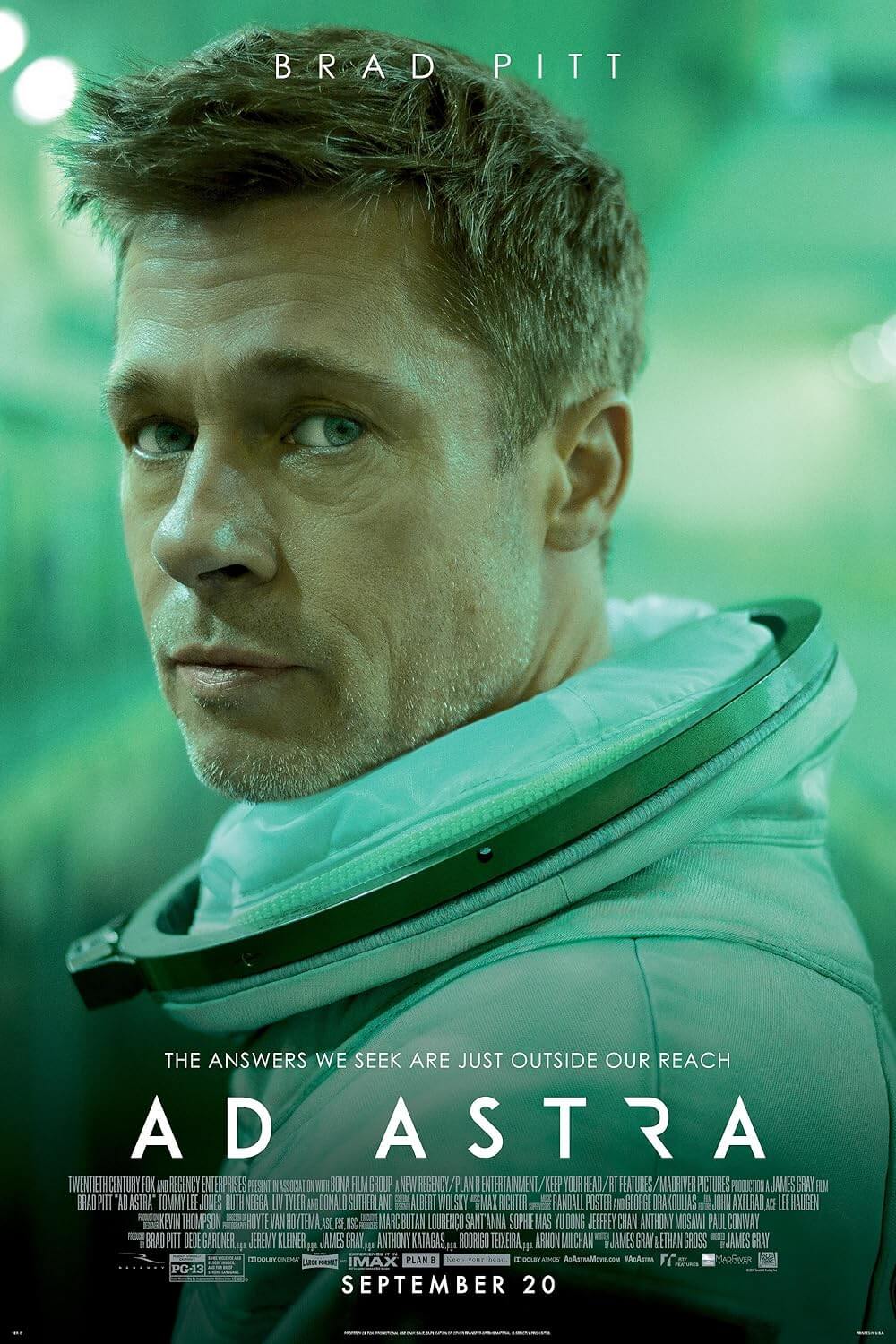

As the opening shot of James Gray’s Ad Astra pans across an image of the Sun and stars, lens flares in the shape of circles shift in the opposite direction. The effect, accomplished as light bounces and scatters from the camera lens, resembles planets aligning. Inside one of those round light artifacts appears Brad Pitt’s insolated astronaut, a dauntless if emotionally distant professional whose pulse has supposedly never risen above 80 beats per minute during stressful situations. The entire shot lasts only a few seconds, but it evokes the entire journey of Stanley Kubrick’s epic 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), a film that carries the viewer beyond the infinite to a place of profound understanding, or confusion. Kubrick’s film begins with a Sun-Moon-Earth alignment and ends with an explorer transmigrating into an ethereal Star Child, an image that comes to mind when we see Pitt reflected in the lens flare, seemingly floating in space. Gray’s film goes on a similar pilgrimage as Kubrick’s, though instead of reaching into our unconscious to achieve existential comprehension, Ad Astra is rooted in a human drama that unravels somewhere between Earth and the rings of Neptune, two stations as distant as the story’s father and son.

Gray has leapfrogged between genres, especially in the last decade or so; however, viewing him as a journeyman would be a mistake. Whether he’s exploring the world of cops and crooks in 1980s New York in We Own the Night (2007) or mounting a David Lean-esque epic with The Lost City of Z (2017), his films bear the distinct stamp of his rather novelistic preoccupations as a filmmaker. His films usually embrace the mechanics of a classical genre and, within that structure, he explores an emotional rawness that grants his characters, usually entrenched in family dynamics, dramatic integrity. His characters often inhabit familiar tropes required of by the genre at hand, but they defy such limitations with their complexity. In terms of technique, Gray has repeatedly demonstrated his appreciation of classical styles, freely adopting them into a subtle formal pastiche, which avoids reducing itself to mere nostalgia. When he occupies a particular genre, he does so with full awareness and commitment to its place in film history—allowing cinephiles to decode Gray’s string of influences—while at the same time delivering something that resists feeling like a reference machine.

With Ad Astra, Gray has sprinkled a wealth of film history throughout his picture like fine moon dust. The viewer thinks of Kubrick in the first shot. Next, Gray channels Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity (2013) when a sudden electromagnetic pulse flashes across the upper atmosphere, where Pitt’s steely astronaut Roy McBride clings to the International Space Antenna—an enormous tower designed in “the near future” by the ruling SpaceCom to locate extraterrestrial life. After a series of explosions, Roy tumbles down, his parachute barely lasting the fall to the planet’s surface. Once he lands, officials debrief the remote but steadfast hero on what has just occurred in a top-secret meeting: Roy’s long-lost father, H. Clifford McBride (Tommy Lee Jones)—who abandoned his wife and son decades ago for The Lima Project, a mission that took him to the edge of the solar system to search for life on other planets—may still be alive. The source of the EMP, which has caused planet-wide power outages and threatens to destabilize all of humanity, comes from the general location of the mission led by Roy’s father, a national hero for having gone farther into space than any other human being. Although Roy believes his father is dead, SpaceCom thinks otherwise, and so he accepts a mission that will take him on a series of stops to reach a communications hub on Mars, where he will reach out to his father via secure “laser” signal.

With Ad Astra, Gray has sprinkled a wealth of film history throughout his picture like fine moon dust. The viewer thinks of Kubrick in the first shot. Next, Gray channels Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity (2013) when a sudden electromagnetic pulse flashes across the upper atmosphere, where Pitt’s steely astronaut Roy McBride clings to the International Space Antenna—an enormous tower designed in “the near future” by the ruling SpaceCom to locate extraterrestrial life. After a series of explosions, Roy tumbles down, his parachute barely lasting the fall to the planet’s surface. Once he lands, officials debrief the remote but steadfast hero on what has just occurred in a top-secret meeting: Roy’s long-lost father, H. Clifford McBride (Tommy Lee Jones)—who abandoned his wife and son decades ago for The Lima Project, a mission that took him to the edge of the solar system to search for life on other planets—may still be alive. The source of the EMP, which has caused planet-wide power outages and threatens to destabilize all of humanity, comes from the general location of the mission led by Roy’s father, a national hero for having gone farther into space than any other human being. Although Roy believes his father is dead, SpaceCom thinks otherwise, and so he accepts a mission that will take him on a series of stops to reach a communications hub on Mars, where he will reach out to his father via secure “laser” signal.

Roy must travel to an intermediate station on the Moon, and from there to a base on Mars, where he’s meant to call his father. Along the way, Gray engages in detailed world-building that immerses the viewer in a distinct, though faintly familiar, future-world. The practical reality of the story takes place in a believable science-fiction setting, filled with intricate details overseen by production designer Kevin Thompson. When Roy lands at his first stop on the journey, the city on the lunar surface, it looks just like what capitalistic human beings would build: an airport concourse, complete with chain restaurants and corporate logos (Applebee’s on the Moon, anyone?). In this embrace of genre, Gray has also conceived several thrilling, episodic set-pieces that make excellent use of superior CGI and visual design. At one point, Roy, escorted by Colonel Pruitt (Donald Sutherland), a friend of his father, finds himself in a breathless lunar buggy battle, something like Mad Max on the Moon—which has become a feudal state of renegade factions. Later, the station on Mars looks like wasted concrete space reminiscent of the post-nuclear structures in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), whereas the cold and flat interiors, accented by vintage birdcages and dolls, recall the visual blend of new and old in Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972).

On the other hand, the science-fiction trappings of the plot do not constrict the tone and theme-heavy style of Gray’s approach. Though the film’s logline could be easily reduced to that of a space adventure by another, lesser filmmaker, Ad Astra is a work entrenched in the theme of fathers and sons, which could be taken at face value, but many will find a religious allegory too. Every sequence seems to have metaphoric implications on Roy’s personal journey and, depending on how the viewer interprets each scene, it could amount to a desperate search for answers from a creator who seems to have abandoned his creation. Replace the word “father” with “God,” and suddenly the film transforms into a crisis of faith, although the stronger experience is rooted in the intimate, familial one. When Roy comes face-to-face with a particular animal at one point, the close-up is mirrored later in the film, when Roy meets his father, and the implications of that association are revealing. Or note how a later scene finds Roy literally wrestling with his father in space, an image that encapsulates the entire thematic intent of the film.

Continuing with the discussion of Gray’s referential touchpoints, Ad Astra bears a similar emotional weight to Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar (2014), combined with the introspective voiceover of Terrence Malick’s cosmic The Tree of Life (2011), another film starring Pitt. Indeed, Gray’s style resembles some of the more straightforward Malick efforts, namely The Thin Red Line (1998) and The New World (2005), where the rhapsodic technique never enters the territory of abstract impressionism. The theme in Gray’s film has not been overly poeticized or visually fragmented in a way that requires demanding interpretation, as some of Malick’s later films (To the Wonder, 2013; Knight of Cups, 2016; Song to Song, 2017). Although, it is lyrical in its use of voiceover and cutting away to images in Roy’s mind. Every line of Roy’s narration serves the theme in searching verse. “I’m being pulled farther and farther from the Sun… to you,” Roy says, whispering to his father in his mind. Regardless, Ad Astra could be accused of being too direct the way it links its themes to the story, as some aspects of the plot represent Gray’s explicit use of symbolism to explore Roy’s emotional journey.

Continuing with the discussion of Gray’s referential touchpoints, Ad Astra bears a similar emotional weight to Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar (2014), combined with the introspective voiceover of Terrence Malick’s cosmic The Tree of Life (2011), another film starring Pitt. Indeed, Gray’s style resembles some of the more straightforward Malick efforts, namely The Thin Red Line (1998) and The New World (2005), where the rhapsodic technique never enters the territory of abstract impressionism. The theme in Gray’s film has not been overly poeticized or visually fragmented in a way that requires demanding interpretation, as some of Malick’s later films (To the Wonder, 2013; Knight of Cups, 2016; Song to Song, 2017). Although, it is lyrical in its use of voiceover and cutting away to images in Roy’s mind. Every line of Roy’s narration serves the theme in searching verse. “I’m being pulled farther and farther from the Sun… to you,” Roy says, whispering to his father in his mind. Regardless, Ad Astra could be accused of being too direct the way it links its themes to the story, as some aspects of the plot represent Gray’s explicit use of symbolism to explore Roy’s emotional journey.

More than any other source of inspiration, Gray seems to draw from Solaris, both Tarkovsky’s original and Steven Soderbergh’s underappreciated 2002 remake. Tarkovsky and Soderbergh serve the emotional states of their protagonists more than sci-fi authenticity of their world—the genre becomes a cinematic language with which to explore theme and character. While Gray has made a work of tactile and convincing sci-fi cinema with Ad Astra, the construction of that world serves his dramatic ambitions. Consider how Roy must record regular psychological evaluations to demonstrate his mission readiness. “I am focused on the essential to the exclusion of all else,” he says. His low BPM and dogged preparedness are symptoms of an emotionally distant person who has already ruined a marriage (to Liv Tyler, seen in memory-images) from his compartmentalization—a detail reflected by his sealed-off appearance in a spacesuit. He is the perfect SpaceCom company man, but the mission breaks down emotional walls, forcing him to acknowledge his feelings of abandonment. Watching the film, the viewer may find Roy impenetrable in the initial hour, but our willingness to empathize with him is rewarded by tender scenes in the second half. Pitt gives a fully realized and nuanced performance, requiring him to conceal and, over time, gradually break down his protective outer shell.

If there’s anything to question about Gray’s message, it’s how he ultimately argues that looking for answers and meaning in the unknown leads one away from the concrete known, representing a painful sacrifice for a futile search. When films such as Contact (1997) and The Martian (2015) underscore the importance of continuing to explore frontiers beyond the limits of our planet to advance the human race, Ad Astra is curiously, perhaps naïvely optimistic about Earth’s future—a detail that has no bearing on the dramatic gravitas, though it does call into question the completeness of Gray’s sci-fi vision. That aside, Gray intertwines his theme and plot in an effortless, perhaps even unchallenging way, allowing the viewer to savor the finer qualities of the film—Pitt’s extraordinary performance, the incredible set-pieces, and the beautifully composed formal strokes—without expending too much thought on what it means. Still, Ad Astra is a rare piece of introspective, sci-fi filmmaking not dependent on some established intellectual property. Films so ambitious, and expertly made, seldom come along, and for that, it deserves to be celebrated.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review